Growing up, Lýdia Budayová’s parents would only tell her stories and fairy tales in Slovak. In fact, she does not remember any books in Rusyn, though it was the language spoken in their household.

Her mother would address her in Slovak when she was a child, but her father and all her grandparents only talked Rusyn to her.

“I started speaking Rusyn only at university, when I became a member of our organisation Molody Rusyny,” Budayová told The Slovak Spectator.

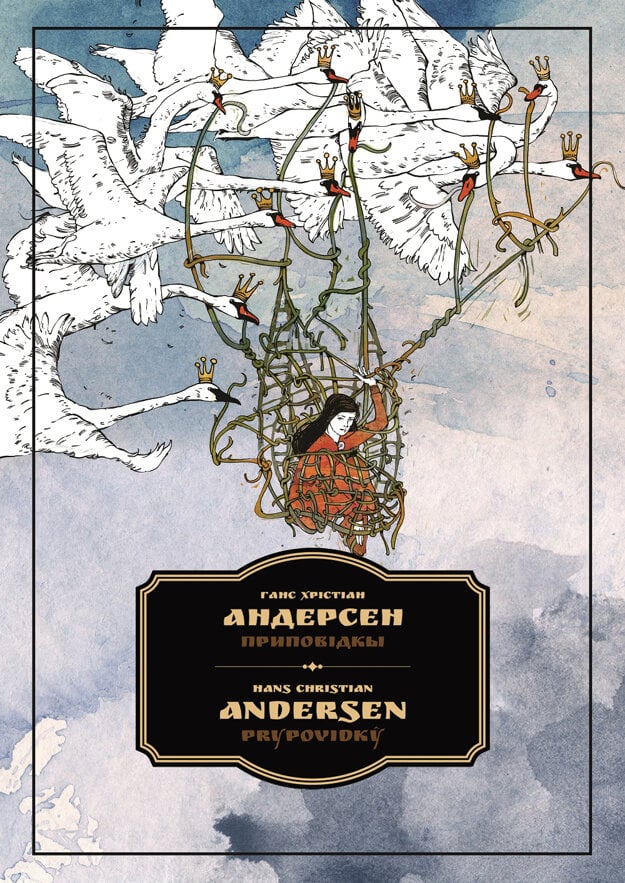

Civic association molodŷ.Rusynŷ (Young Rusyns) unites some 30 people of Rusyn minority, leading the way in the informal movement that seems to have arisen around people who are increasingly becoming aware of their Rusyn roots. One of their recent initiatives to support cultivation of Rusyn in children and their parents is to address the lack of children’s books in their native language: they decided to raise money to publish the first-ever translation of a world fairy tale collection in Slovakia. They chose Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales as those do not require further introduction to readers.

“As young Rusyns, we wanted to offer something to the youngest generation, the Rusyn children,” said Budayová, who is the book’s editor.

From architect to book editor

Budayová is an architect by profession, so children’s book editing was a big leap. However, with support of the organisation, she realised that it was possible if she found a translator and an illustrator, along with the money.

The association requested a grant from the Culture Ministry also embarked on a crowdfunding campaign. They succeeded in collecting more than €4,000 for the book and also the first pre-orders.

(Source: Lýdia Budayová)

(Source: Lýdia Budayová)Budayová says the choice of book was hers: Andersen is her favourite author.

“Those stories are not only for children, they are also a criticism of society and as an adult I still enjoy reading them,” she noted and pointed to the ethical issues the stories raise.

Cyrillic and Latin alphabet

They chose 20 out of 40 stories in the Slovak translation by Milan Žitný, among them The Princess and the Pea, Thumbelina, The Nightingale, The Snow Queen, The Ugly Duckling, The Emperor’s New Clothes, The Steadfast Tin Soldier, and The Little Match Girl. The book was translated into the codified Rusyn language officially recognised in 1995.

Rusyn or Ruthenian?

The language spoken in eastern Slovakia is Rusyn, and the people there also call themselves Rusyns, but they use “Ruthenian” when talking about the wider ethnic group (in Poland, Ukraine and elsewhere).

The cross-border area where they live is also referred to as “Ruthenia”. In English, “Rusyn” and “Ruthenian” are often used interchangeably.

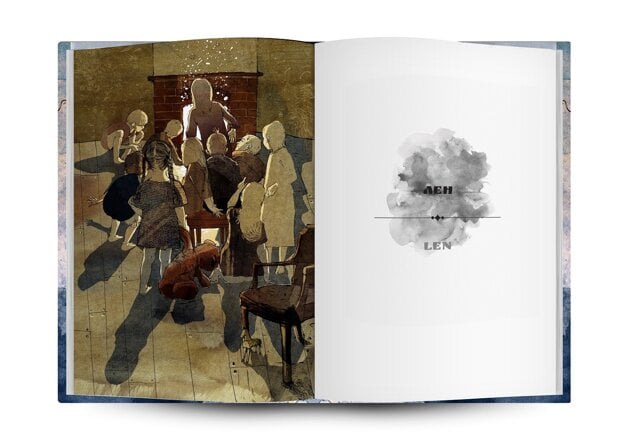

Each story is written in both the Cyrillic and the Latin alphabet. Budayová explained that Rusyn is officially written in Cyrillic, but since the book is published in Slovakia and people in Slovakia are more familiar with the Latin alphabet, they decided to include the transcription so that even children or parents who cannot read Cyrillic would be able to read the stories in Rusyn. The book will be complete with a dictionary of selected Rusyn words translated into Slovak.

Three of the stories were translated by Alena Jancurová, who said that her family always talked in Rusyn at home, as it was natural for them. She stresses the advantage of Cyrillic and Latin alphabet in the book. Even though she does not have any problem with reading both, as she studied Russian, she knows that even her peers have a hard time reading Cyrillic.

“Most of my generation and younger people have not encountered Cyrillic and if they have, only marginally,” she noted. “That’s the reason I like that the book will be published in both alphabets and the reader will have the possibility of comparing and maybe even learning something when reading.”

She noted that one problem with Rusyn books is that for most people they are not accessible, as they do not know how to read the letters.

Pitfalls of translation

When translating the fairy tales, Jancurová encountered several difficulties of the language. In the past, Rusyn inhabitants lived mostly in villages and this environment also defined the vocabulary of the language.

“In short, the Rusyn language lacks a predominantly abstract vocabulary, which developed mainly in cities, as well as the current technical terms that can only be taken over into the language,” Jancurová noted. “You just have to play with it a bit longer for any translation.”

Anna Kuzmiaková, who translated the other 17 fairy tales, said she always used Rusyn, her mother tongue, to communicate with her family, as well as with her peers in primary and secondary school and her university colleagues.

(Source: Lýdia Budayová)

(Source: Lýdia Budayová)She started dealing with the Rusyn language professionally in the 1990s as a reporter. Until 1995, she was part of a team that prepared linguistic documents for the codification of Rusyn for the press.

In January 1995 Kuzmiaková was in Bratislava at the solemn declaration of the codification. “This means that for me, who has been communicating and creating in the Rusyn literary language for 26 years, that it is no longer specific, though 26 years is still a young age for a language, because language is a living organism that is still evolving.”

Books for schools and libraries

The association raised enough money to print 300 copies of the book. They plan to send more than half of them to Rusyn kindergartens, schools, libraries and other cultural organisations.

“We want to let children know that Rusyn can be a literary language and if some of them write one day, it might inspire them to write in Rusyn,” Budayová hopes, adding that it may also further inspire them to seek Rusyn literature and cultivate the language.

Rusyn minority in Slovakia

The Rusyns come from the Carpathian region sprawling the territories of today’s eastern Slovakia, south-east Poland, western Ukraine, northern Romania and north-east Hungary. After the fall of the totalitarian regime in 1989, Rusyn was officially recognised as a national minority, and the Rusyn language was codified in 1995.

In 2011 census, it was the third biggest minority after Hungarian and Roma. More than 33,000 people claimed allegiance to Rusyn minority. They are minority without homeland.

There is an Institute of Rusyn Language and Culture at Prešov University. Perhaps the most famous descendant of Slovakia’s Rusyns was Andy Warhol, whose parents emigrated to the USA from the village of Miková, now eastern Slovakia.

This article is part of the Our Minorities project, carried out with the financial support of the Fund for the Support of the Culture of National Minorities.