The solid growth that Slovakia has been experiencing over the past three years should continue in 2018 – and even gear up a bit – close to 4 percent in real terms and possibly even more in 2019 when the Jaguar Land Rover plant in the Nitra region will start producing at full capacity. Cyclically, Slovakia is narrowing the slack in the economy, with the labour market entering a full employment scenario. This will result in growing pressure on wage costs and bringing in foreign labour. For investors looking at the longer term horizon, a growing shortfall of skilled domestic workers and other adverse demographic trends will indeed be the major structural issues to cope with in Slovakia.

Strong EU tide propels all boats

The Slovak economy has done well in the first half of 2017: real GDP grew by 3.2 percent, much like in the preceding year and seems on paper to post a full-year growth of 3.4 percent. Slovakia’s positive achievements though are no exception in the region. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland all look likely to deliver full-year growth of 4 percent, while the Romanian economy nears 6 percent growth.

The whole region benefits from the same forces that drive the Slovak economy. Strong western European demand and robust domestic consumption. It thus makes sense to look at the Slovak growth story from the perspective of the whole central European region rather than in isolation. The main difference in the growth dynamics stems from the pace of recovery of investments, especially of EU-funded projects.

Indeed, the slow drawing of funds was the main reason why Slovakia’s investment and overall GDP growth in the first half of 2017 lagged behind neighbouring countries.

Signs of some overheating

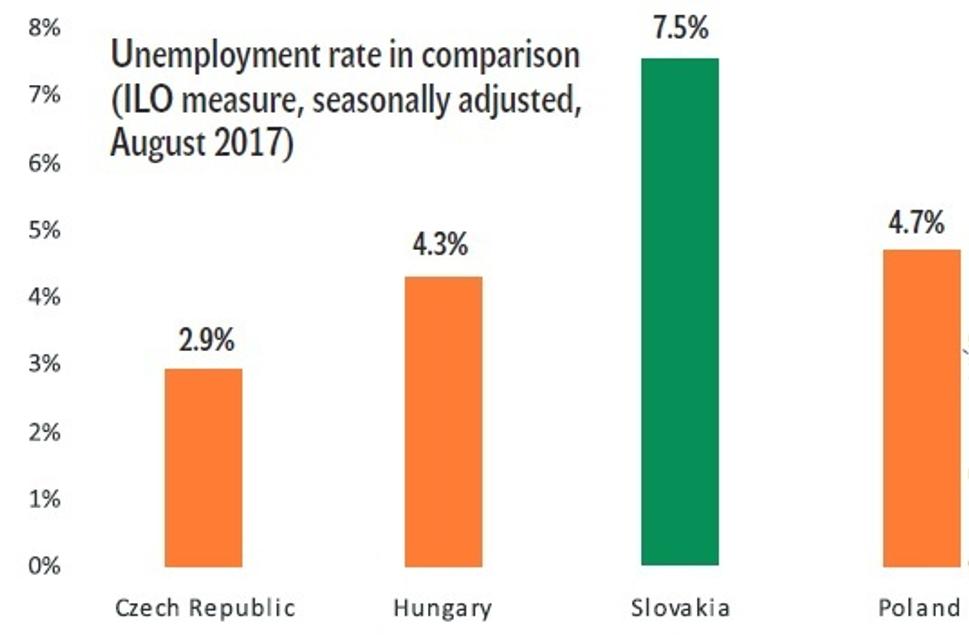

Tight labour markets with labour shortages are a common feature in central Europe. In Slovakia, the unemployment rate fell in August for the first time below the EU average, to 7.5 percent. The registered unemployment rate, calculated from the number of jobless registering with labour offices, even fell to an all-time low of 6.5 percent in August. While historically low, these Slovak rates pale in comparison to the Czech unemployment rate of 2.9 percent, the EU’s lowest.

Against historically low unemployment, unsurprisingly, wage growth is also picking up. In Slovakia, though, the acceleration so far has been rather tame. By the second quarter, gross nominal wages were up 4.8 percent year-on-year. In the Czech Republic, meanwhile, the corresponding measure of wage growth rose to 7.6 percent and in Hungary, where labour shortages are most acute, even to 14 percent, respectively.

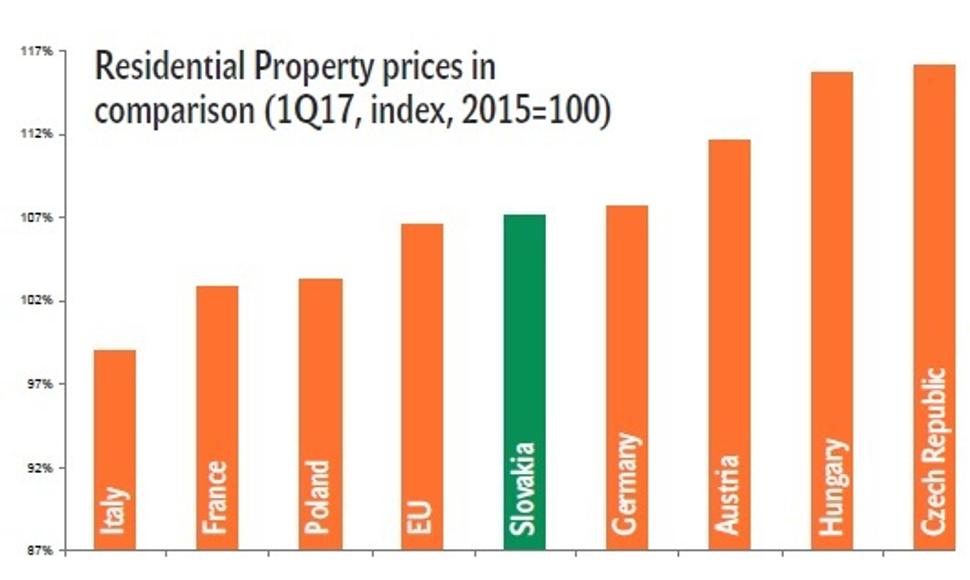

Broader inflation figures only complete the picture of the central European region heating up from the economic cycle point of view. In particular, property prices have risen to among Europe’s fastest growing.

In the year ahead, the hitherto growth drivers – exports and consumption – will likely remain forces of the Slovak, and indeed, the region’s economy. Moreover, the eurozone is doing well. Economic sentiment improved to a multi-year high, suggesting growth will remain stronger than the trend. Moreover, the overall GDP growth of the eurozone is likely to moderate from this year’s estimated 2.2 percent. Amidst times of an appreciating euro, namely the acceleration phase is gradually ending.

Illustrative stock photo (source: Kia Motors Slovakia )

Illustrative stock photo (source: Kia Motors Slovakia )

(source: Eurostat, VÚB)

(source: Eurostat, VÚB)

(source: Eurostat, VÚB)

(source: Eurostat, VÚB)