He has spent more than a half-century near the water. Underneath the water, in fact, as he dives to uncover the mysteries of the water. Fish are a passion of Peter Áč’s. He has taken part in several expeditions in European and tropical seas, but he spends most of his time by his beloved Danube river and its arms. "Diving used to be an adventure because we knew nothing about it and had no equipment," said the scientist, zoologist, publicist and photographer. "Now, you pay for a tour, they put the most expensive diving suit on you and push you into the water to show you a big whale shark, and you're happy."

What made you start diving?

As many other boys, I enjoyed going to the Tehelné pole lido in Bratislava. There, another young boy had goggles that he put glass into to prevent them from getting fogged up. He lent them to me. It was my first underwater look, and I was hooked. My father, who was a passionate fisherman, often took me to the water. If he didn't catch anything, he complained that no fish were in there. But when I put my head underwater, I figured there were plenty of fish. They just didn't want to get caught. And that was the beginning.

What equipment did you use, at first, to dive?

I made my first swim goggles out of an inner tube, which I glued glass into. It was perfect because I could see everything.

You must have improvised a lot in the beginnings.

Sure. We had nothing. You know what my first swim fins looked like? I threaded a piece of linoleum to my gym shoes. It was a disaster. I nearly drowned myself.

Have you ever teetered on the edge of dying underwater?

Sometimes, but I've survived. You have to have good luck. I've always had it underwater, but I once fell down off a roof and broke my spine.

Did you dive on your own?

Not at all. We were a group of enthusiasts, made up of medicine students, two design engineers, geologist Janko Senes, linguist Alexander Ivan and others. We set up an underwater research group within the Czechoslovak Zväzarm paramilitary organisation. We were diving in the Adriatic Sea as well as in the mountain lakes of the Tatra mountains. The group was in operation until we got cancelled.

What was the hardest thing in those pioneering times ?

It was Hans Hass, an underwater diving pioneer and explorer of underwater beauties, who used to say that a diver's biggest enemy is cold temperature exposure, not a shark. Your body quickly cools down in the water.

How did you cope with it?

In our own way. I recall a cheerful story. We used to go to the lakes in the Mirror Orchard of the Petržalka borough. There was nothing but a border area around the location where the neighbourhood now stands. With Vojto Slacik, a friend of mine, we smeared tallow on our bodies, we put on wool jumpers, long underwear, swim caps, under which we also placed woollen hats. In a sheath, we had a kitchen knife because no diver can survive underwater without a dagger. This was how we used to dive. When border guards, riding on horses, came and spotted two strangers in long underwear, they regarded us as obvious invaders. By the time they rode around the lake, we had swum over to the other side and run towards a bus station. Without clothes, in our long underwear.

Did tallow smeared on your bodies help you?

Absolutely not. It was just a myth. We only made the water dirtier.

When did the first neoprene sportswear appear?

Professor Balon brought the first one from America where he had attended a congress. We examined it inside and out, but we didn't get the principle. Zbyňo Pekár had contacts in Bratislava's Matador rubber plant. He managed to obtain foam-rubber slabs, which we then taped diapers to. Diapers often tore apart, causing water to be absorbed by the slabs, which was a disadvantage. Later, we began to produce dry-suits, which were of a completely different quality.

Why did you start taking a camera underwater?

When we spoke of what amazing things we had seen underwater, nobody believed us. We wanted to prove it. So, I started to ponder how to eternalise those images.

Had you practised photography before?

No, I began as soon as I got under the water. Later, I started to make money taking photographs of anything to be able to afford my hobby – underwater photography. For example, meat, shoes, but never the girls.

Whom did you take pictures of meat for?

Zverimex asked for a game catalogue so I had to take pictures of the game. It is very difficult to take photos of fresh meat in an atelier. It quickly oxidizes and changes its exterior colour. As a biologist, I've always been attracted to water.

What did your first underwater photography experiments look like?

My first underwater camera consisted of a wooden box and a camera in it. I puttied it, and the shutter was then released by a rubber band off a dropper. I had to emerge from the water after each shot and repeat the whole thing. Again, and again.

How old were you then?

About eighteen or nineteen.

In your collection, you have 40,000 photographs, mostly of fish and other aquatic animals. What fascinates you so much about them?

Through the years, I've captured all our freshwater fish. Later, I began to deliberately follow their way of life under the water. I realised ichthyofauna in its natural environment had not been documented. There's a story behind each photograph of mine.

Sixth at the championship

Peter Áč participated twice in the underwater photography world championships, in Menorca and Norway's Alesund where participants competed in three disciplines – wide-angle photography, macro photography and creative photography. The event lasted two days. Competitors plunged into water for two hours, organisers marked photographic films, competitors produced transparencies and chose two pictures for each category, which were judged by a thirteen-member jury, Áč said. "In the macro photography category, I once finished sixth, which was a nice result taking into account the competition."

Tell me at least one.

I was taking photos of the nase spawning in the Dunakiliti dam. I laid still in the shallow water for an hour, then the fish got used to it and began to leap around in front of my camera. Some passer-bys then appeared, poking me with a stick. They were trying to figure out whether I was alive, or an Austrian drowned to death, found in Slovakia's split of the Danube River.

Why is the Danube unique to you?

For its existence, really. It is the second longest European river after the Volga. Before the hydroelectric power plant was constructed, it had been an element, massive water shaping its arms. You never knew how it would end. The Danube and its surroundings used to be a different country. Fortunately, I experienced it.

So, you can compare. What was the Danube like before the Gabčíkovo power plant and after it was built up?

I first held the opinion that the dam wouldn't have to be bad, it would be different but life would go on. But it's no good. When floods used to occur now and then, it helped clean the Danube arms in its inland delta. Now, the old riverbed of the Danube has no water, and the arms have turned into ponds with a bit of water floating in them. The habitat and fish species composition have completely changed. I see it as very harmful. On the other hand, the Danube has opened up to more people. You meet more cyclists and tourists. Don't get me wrong if, as a biologist, I'm not too happy about it. I'm also mad because fishermen were banned from floodplain forests, but hunters can still go in, even driving their cars with carts there.

Do you dive in winter?

Of course. Winter is fantastic because the water gets clarified. It is minus ten degrees Celsius outside, everything on you is getting frozen and suddenly, you come across hibernating sazans at a depth of eight metres. No wonder you must dive in…Taking photos in winter and under the ice is an unusual and beautiful discipline. Few photographers practise it, though.

What is a sazan?

The sazan is a cult fish. It is a wild carp different from the one cultivated for food preparation. It still lives in the Danube but is becoming extinct. Look, it's got a typical longish body. It's interesting the sazan has managed to survive significant changes to the Danube.

What fish was the hardest to take a photo of?

For instance, the asp.

Why?

Taking photos of freshwater fish is based on its behaviour. You have to know the way of its life. It's easy to take a picture of the esox. It does not move, thinking you can't see it. But the asp swims in the water. You may spot it accidentally and no matter when it surprises you, you must be prepared.

You also have photos of river crabs. Is there enough clean water for them in the Danube arm?

Yes.

You took pictures of the legendary Danube fish, the beluga.

The beluga sturgeon is the largest freshwater fish, which originally lived in our Danube, too. I've heard some efforts happened to bring it back to the Danube, but I do not believe it. It would be costly. I had luck to take photos of the beluga, and it was amazing. The beluga doesn't pay attention to your presence in the water when it hits you. It is like getting hit by a battering ram. I think nature itself can cope with the situation. Just like in case of beavers. They were not here for 150 years, and they're running around here now.

How did you make the unique underwater shots of a hunting heron?

It was the result of several years of effort. I baited it. It is a wild heron, which I call Žofia. It has been coming here for four years. I must say it fascinates me. Since it got used to me, I've taken around a thousand pictures of Žofia.

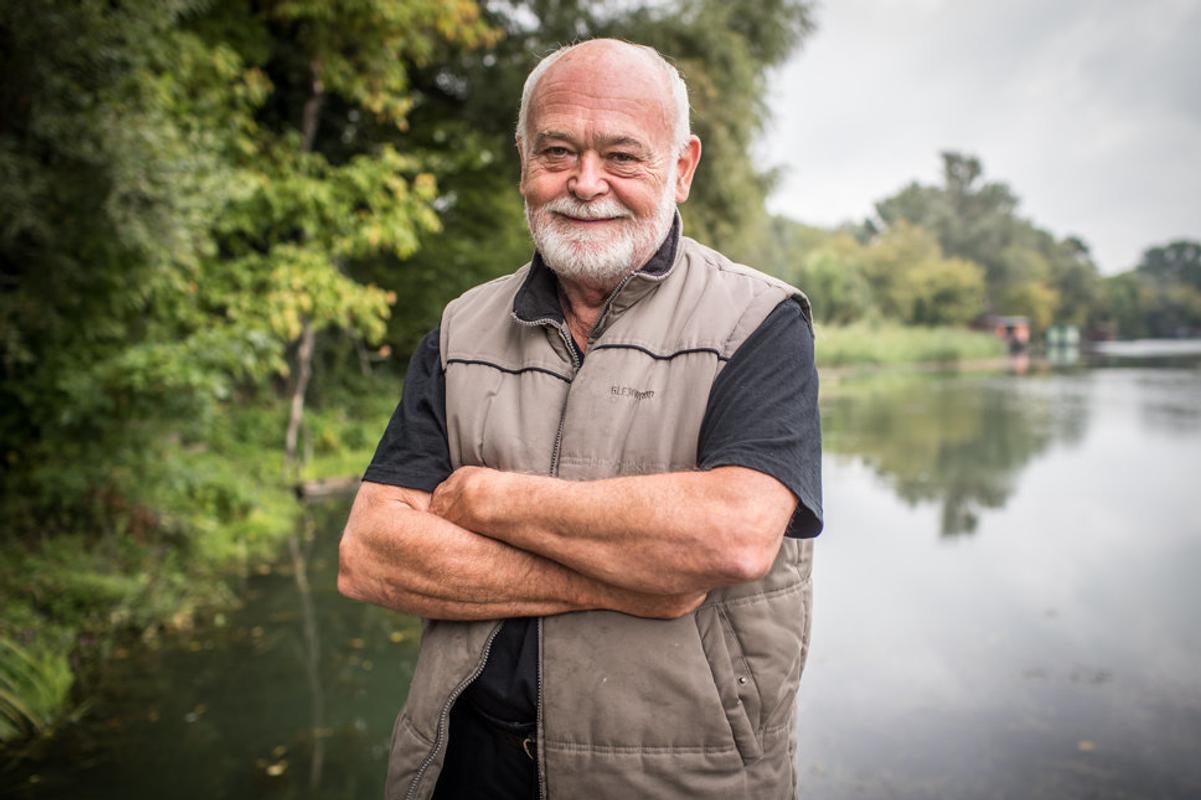

Peter Áč (75)

Slovak natural scientist, zoologist, publicist and photographer, Peter Áč has been an expert in underwater photography for 50 years. He took part in several diving expeditions to European and tropical seas, but fresh water has remained the centre of his work, mainly in the Danube region. He is author and co-author of over 90 scientific and scholarly works and several monographs. In his archive, he has more than 40,000 photos, which can be found in books (The Danube, River of Life and The Secret Life of Fish, Slovak Primeval Forests, Heart of the Great Rye Island and others), calendars, but also at exhibitions. When he retired, he moved from Bratislava, where he lectured on ethology, the study of animal behaviour, at the psychology department of the Faculty of Arts of Comenius University, to Bodiky, a settlement lying on the island between the old Danube riverbed and the Danube's artificial channel.

Peter Áč (source: Sme - Jozef Jakubčo)

Peter Áč (source: Sme - Jozef Jakubčo)

Eurasian beaver (source: Peter Áč)

Eurasian beaver (source: Peter Áč)

Sazan, a wild carp living in the Danube. (source: Peter Áč)

Sazan, a wild carp living in the Danube. (source: Peter Áč)

The remains of the inland Danube delta (source: Peter Áč)

The remains of the inland Danube delta (source: Peter Áč)

Žofia the wild heron (source: Peter Áč)

Žofia the wild heron (source: Peter Áč)