Ladislav Mednyánszky, a Slovak-Hungarian painter and aristocrat, never forgot the love of his life, Hungarian wagoner Bálint Kurdi, and frequently pilgrimaged to Kurdi’s grave in the Hungarian town of Vác.

After Kurdi died of pneumonia in 1906, the painter continued to hold his love dear and talk to him through diaries, where Mednyánszky addressed Kurdi as a pure soul. He shared the ups and downs of his life with “Nyuli” and expressed hope that they would reunite one day. After Kurdi died of pneumonia in 1906, the painter continued to hold his love dear and talk to him through diaries, where Mednyánszky addressed Kurdi as a pure soul. He shared the ups and downs of his life with “Nyuli” and expressed hope that they would reunite one day.

Nyuli was the painter’s nickname for Kurdi, meaning “bunny”in Hungarian.

“The old dog [the painter] belongs to Nyuli,” Mednyánszky wrote in 1908.

Towards the end of the same year, despite the frequent questioning of whether he was worth Kurdi’s love, he penned down a resolute wish to be buried next to Kurdi when the time comes.

Born into a Hungarian family in 1852, Mednyánszky spent his childhood at manor houses in Beckov and Strážky, towns in Upper Hungary, the territory of today’s Slovakia, and later travelled around Europe to develop his talent as a landscape and figure painter.

His landscape paintings, influenced by different art movements but still very much unique, top the list of the most expensive works of art sold in Slovakia. The “Evening Mood” painting from 1911 was sold for €600,000 during an auction in 2016, and the 1900 “Forest Interior with a Brook” painting was auctioned for €230,000 six years earlier.

However, Mednyánszky considered figure painting to be of more importance.

Adopting a tramp life

In his nearly 4,000 oil paintings and several thousands of drawings, Mednyánszky commonly portrayed Roma men, peasants, tramps, rabbis, old men, and soldiers.

Women rarely appear as the subject of his interest.

Homosexuality, in experts’ opinion, played a big role in his selection, in addition to his tramp instinct, criticism of social problems, and his emotional ties towards the lowest class of people that date to his teenage years spent in Strážky, the Spiš region.

Because Mednyánszky grew up surrounded by conservative-thinking people and Hungary was a country where homosexuality was criminalised, he initially saw painting as a means of taming his physical needs.

Yet, as his diaries show, he felt affection for Blazsej Ladeczky, a married shepherd in the mid-twenties who worked in Strážky. The young man, one of Mednyánszky’s first loves, died in 1881.

“I wandered off to you and slept next to your grave soon after I cried,” the painter recalled in a moving diary entry a year after Ladeczky’s passing.

Habitual meetings with men outside his social circles and the influences of Buddhism and philosophy, which the painter explored on his travels, led Mednyánszky to the conviction that he should abandon his privileged life and materialism.

“The experience of periphery became the experience of identity for him,” art historian Csilla Markója wrote in “Ladislav Mednyánszky”, a publication jointly produced by the academies of sciences of Hungary and Slovakia.

As the artist aged, he started to resemble a tramp.

Drawn to strong men

His paintings and drawings, which are simple, impassioned and dramatic, depict strong men who were different from how Mednyánszky would have been described - a man of poor health and different faces. Melancholy and depression alternated with humour and sociability.

“The artist perceived strength and animality as highly positive qualities, synonyms of a natural, simple, happy experience, that were not granted to him,” said contemporary art curator Alexandra Tamásová of the Slovak National Gallery.

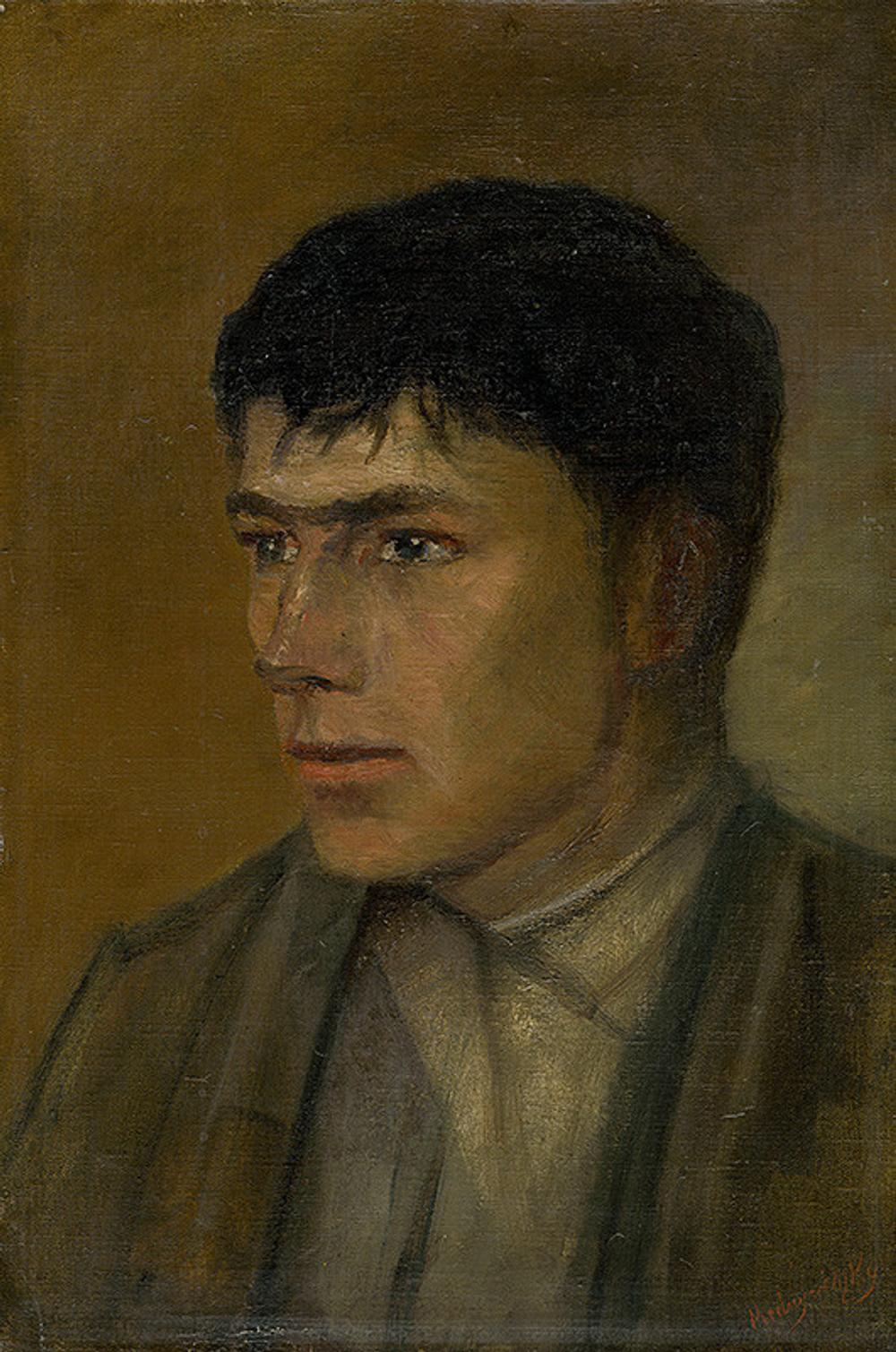

She has recently selected Mednyánszky’s “Portrait of a Village Boy”, produced at the peak of the painter’s artistic career, for the gallery’s “Window Display” project to join the Pride Month celebrations in Bratislava.

Not only did Mednyánszky paint this type of men, but he also set out on amorous adventures with some of his models. They did not last long.

Markója pointed out in the book that “homosexuality made him live a mobile and promiscuous life linked to wandering and hiding.” In these poor men, his models and friends, whom the painter helped whenever he could, Mednyánszky strived to find the “embodiment of idealised, pure morality”, the art historian explained.

He found purity and morality in the love of his life, Bálint Kurdi, which he confessed in his diaries only after Kurdi’s death. Yet the painter himself never felt good and pure enough to serve him.

Matchbox as a sign

Mednyánszky and Kurdi met for the first time in Vienna, where the painter had one of his ateliers, in 1881.

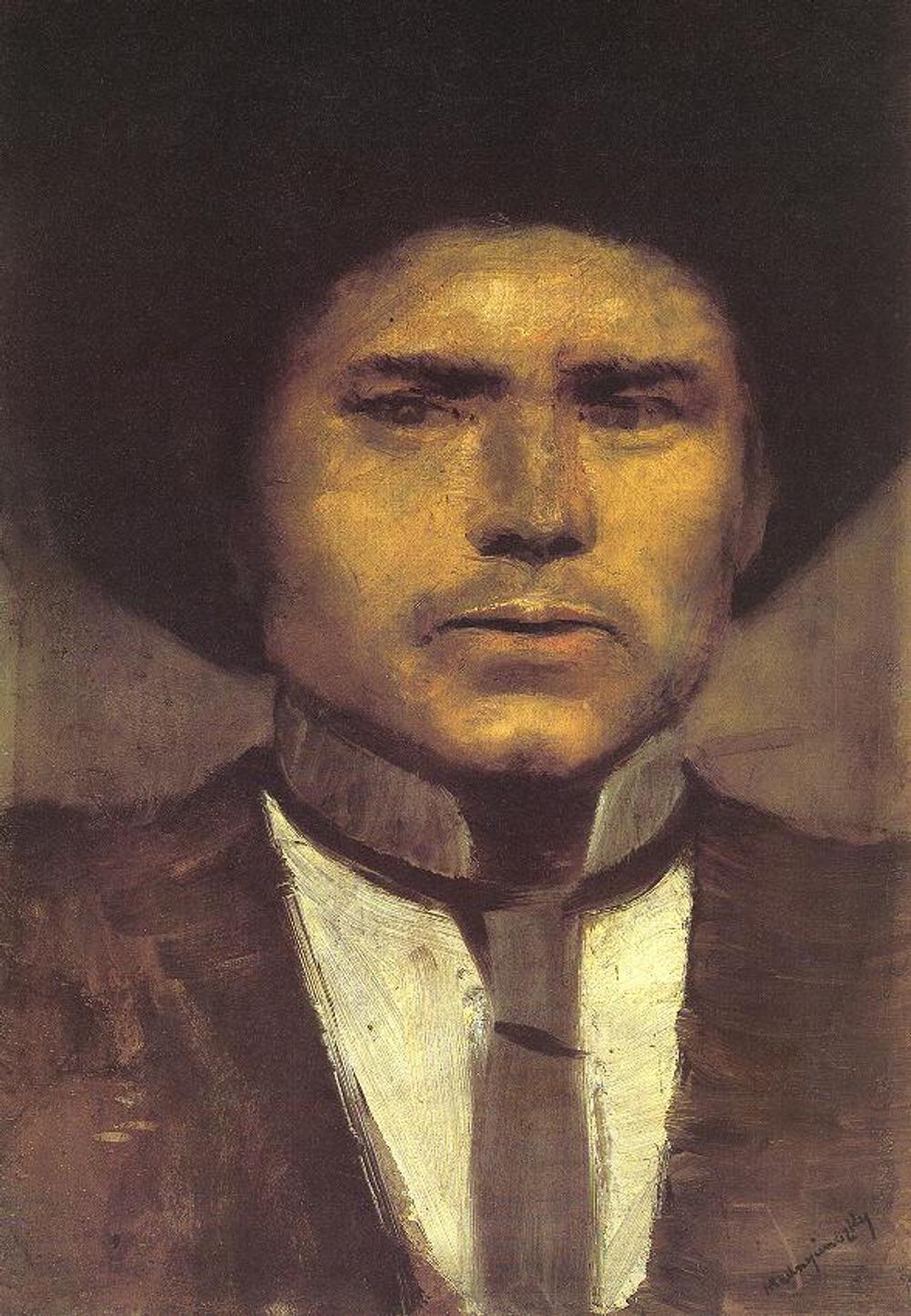

Kurdi, who was 21, was serving in the local barracks. He agreed to posing for Mednyánszky, who was eight years older.

“The Portrait of Bálint Kurdi” essentially represents the painter’s image of the ideal man, according to curator Zsuzsanna Bakó. “This painting exudes a festive atmosphere and impressive self-confidence, pure, open sincerity,” she argued in the “Ladislav Mednyánszky” book.

In Hungary the painter and Kurdi’s friendship continued to evolve over the next 25 years, even though Kurdi married a woman.

When Kurdi died, it was Mednyánszky who paid for a tombstone and bought a place for himself next to the love of his life. Kurdi’s wife, Erzsébet Rózsa, married another man.

Art historian István Bardoly, who read and rewrote Mednyánszky’s diaries, published in 2019 by the Slovak National Gallery, noted in the book of diaries that Kurdi has been perceived as the black sheep of his family and his relationship with the painter, like his sexual orientation, has never been a secret in Vác.

Mednyánszky was rather careful, at least when it came to his writing. He oftentimes wrote his diaries using the Greek alphabet to hide the content of his diary entries. For example, Δ, delta, represented sex or physical contact and Ψ, psi, stood for spirituality, experts found.

The painter mentioned homosexuality in his diary only in 1912, using a passage copied from a book. Homosexuality, though immoral, is better than heterosexuality because it leads to awakening and freedom instead of suffering, the passage in German suggests.

Nevertheless, there are many places in the diary where Mednyánszky misses Kurdi.

In a December 1907 entry, which he wrote in Budapest, almost a year after Kurdi passed away, Mednyánszky spoke of a sign, a matchbox with a bunny printed on it, that he had found on the pavement. Bunny was Kurdi’s nickname invented by the painter. In another entry, he considered building a small house on a hill near the Vác cemetery to be closer to Kurdi.

The painter described the town of Vác as his home, which he could not bear being far away from in the first year after his lover’s death. Kurdi was born and lived there.

“Vác became the centre of my life, and even though I found the biggest sorrow there, I love the town and the whole area to which I am bound by sweet memories,” he wrote in summer 1908, during his time spent in Strážky.

Today, a local manor house in Strážky serves as an art gallery devoted to Mednyánszky.

Buried in Budapest

Attracted to disasters and suffering, the painter endeavoured to take on his last big project during the First World War and became a war painter.

He captured the suffering of soldiers on several fronts over the course of four years.

In Bakó’s view, the paintings of soldiers resemble the paintings of tramps.

The war did not stop Mednyánszky from communicating with Kurdi, despite a lot of work on the fronts and in his ateliers.

In 1915, the aging painter, aware of his health problems, noted down in the diary that the day they would meet was drawing near.

“I will then tell you about everything I’ve experienced since you, my sweetheart, disconnected from this earthly life.”

Mednyánszky died April 1919 in Vienna. Today, he is buried in Budapest.

His wish to rest in peace by Kurdi’s side was never fulfilled.

Slovak-Hungarian painter and baron Ladislav Mednyánszky sits on a stool and paints in his atelier. (source: Slovak National Gallery/Ladislav Madnyánszky)

Slovak-Hungarian painter and baron Ladislav Mednyánszky sits on a stool and paints in his atelier. (source: Slovak National Gallery/Ladislav Madnyánszky)

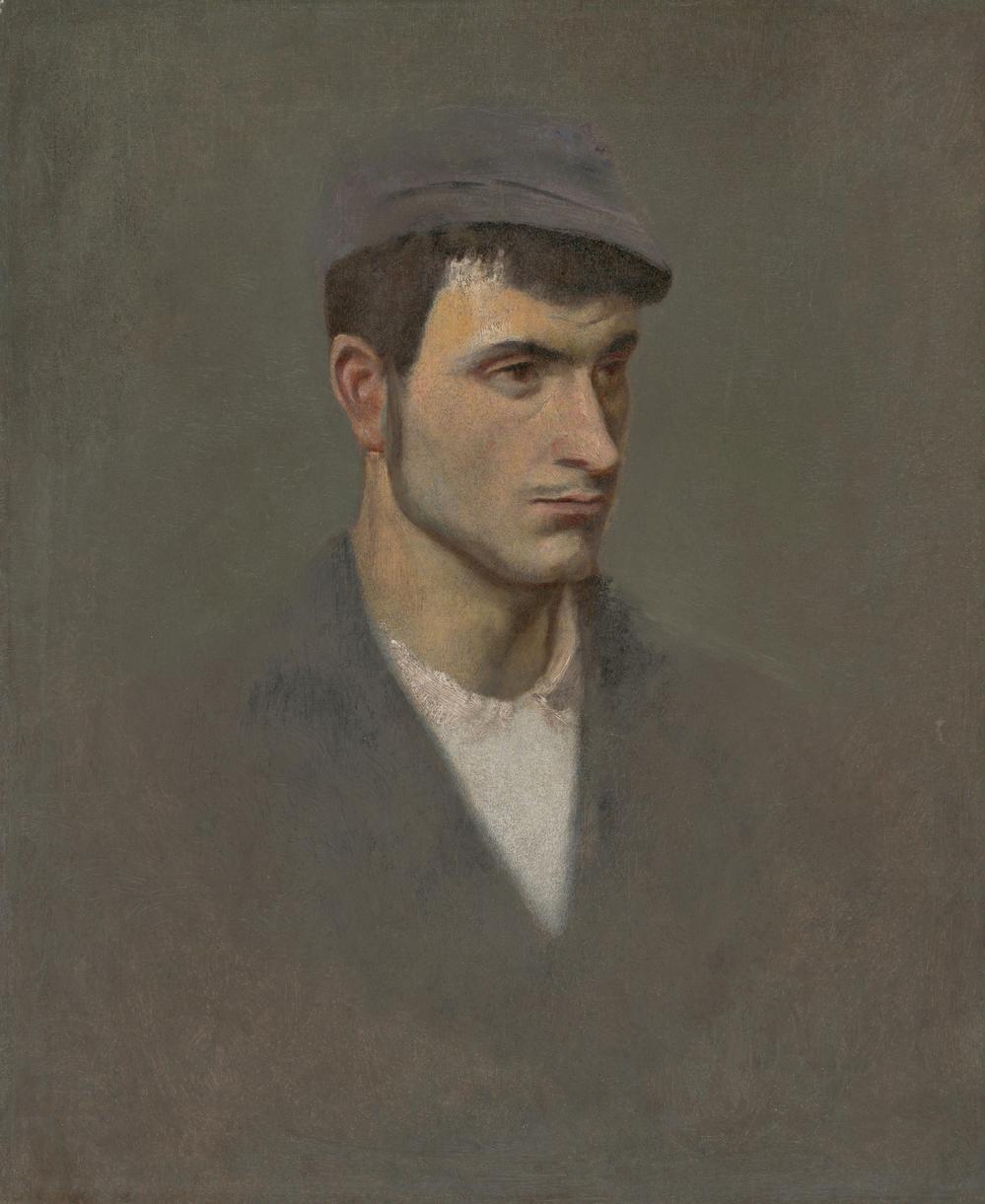

Man in Half Profile (1890) (source: Webumenia.sk)

Man in Half Profile (1890) (source: Webumenia.sk)

Portrait of a Village Boy by Ladislav Mednyánszky (1910-1914). (source: Slovak National Gallery)

Portrait of a Village Boy by Ladislav Mednyánszky (1910-1914). (source: Slovak National Gallery)

The Portrait of Bálint Kurdi (1882-1885). (source: Wikimedia)

The Portrait of Bálint Kurdi (1882-1885). (source: Wikimedia)

The Portrait of a Soldier (1914). (source: Webumenia.sk)

The Portrait of a Soldier (1914). (source: Webumenia.sk)