Miroslav Cipár, one of Slovakia’s most versatile artists, experienced a life that covered all of Slovak history in the last century.

This encompasses the emigration of Slovaks to America, poverty in remote areas, WWII, Nazi terror, Russians and the Slovak National Uprising, the repeated defeat of democracy by fascism and communism, violent nationalisation, totalitarianism and its fall in November 1989.This encompasses the emigration of Slovaks to America, poverty in remote areas, WWII, Nazi terror, Russians and the Slovak National Uprising, the repeated defeat of democracy by fascism and communism, violent nationalisation, totalitarianism and its fall in November 1989.

But it was art that played an even more significant role in his life, creating plenty of original visual works.

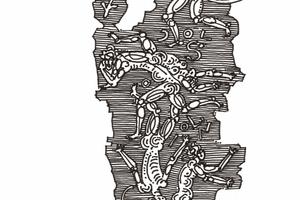

Only last year, at the age of 85, the talented illustrator, painter, graphic artist and sculptor received a special gift - the main prize for the most beautifully illustrated book of 2020 for Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, an important European work about the path to the salvation of the soul.

“It was a challenge to illustrate such a work,” Cipár then said. “I had to get through the whole text, at first I felt like I was drowning in it. So, I had to go back to the beginning and start again.”

He did not reveal how long it had taken him to illustrate the book. Nor did he manage to bid farewell to the world of art and to anyone he would have wanted.

The Slovak artist died on November 8, 2021. He was 86.

Childhood in Kysuce

Cipár grew up in one of the scattered communities in the Kysuce region in the north of Slovakia. The community called Semeteš lies in the middle of forests, not far from the river Kysuca springs, and the Czech region of Moravia right behind the Makov Pass.

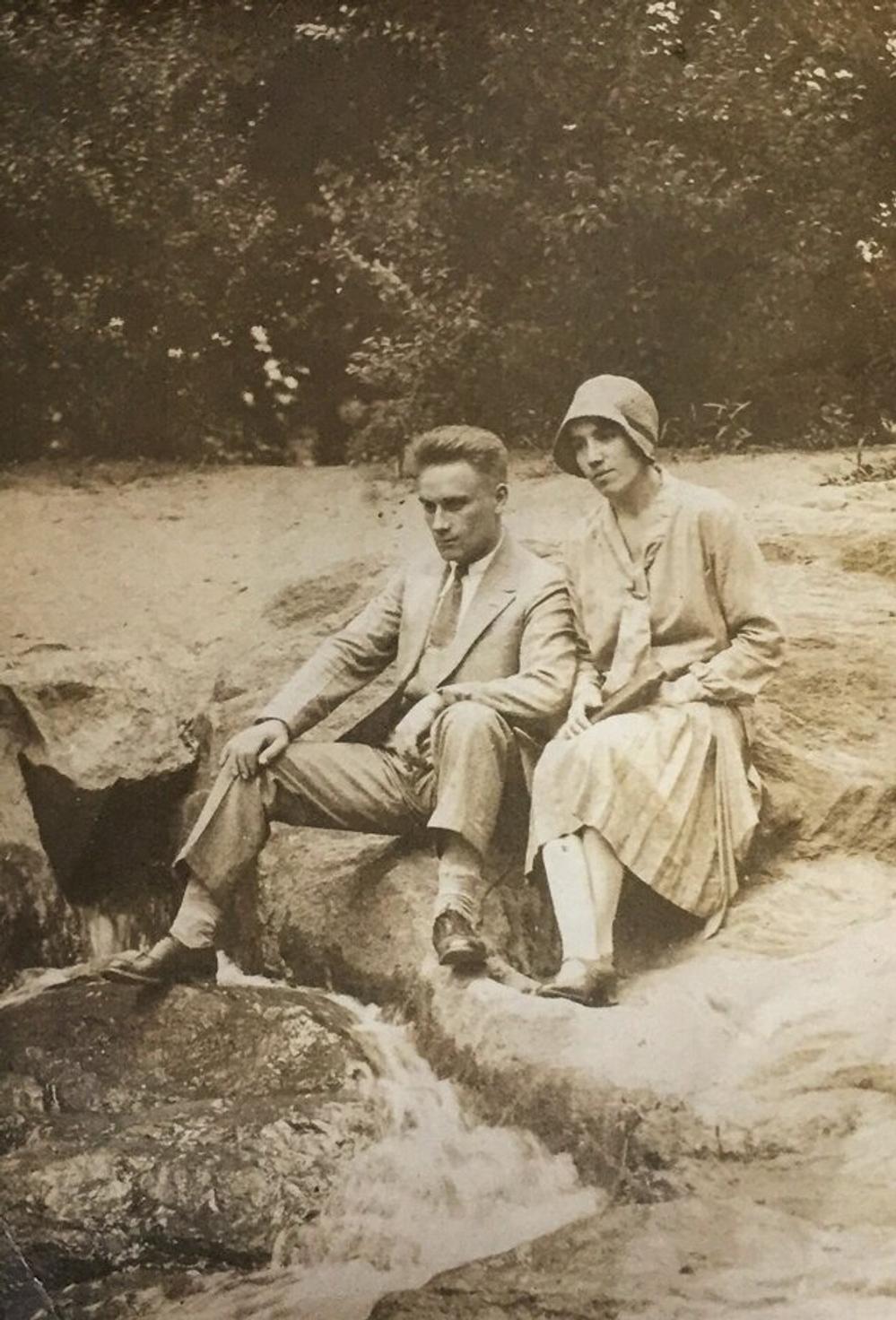

His grandfather opened a small shop and pub, selling flour, sugar and kerosene. His father was an American. He left for the USA, where he worked at a New York wireworks. Lights in theatres and cafes enveloped in wire structures may have passed through his hands. When he saw that he was doing well, he returned home for his wife.

"My parents did well in America and my mother also liked it there. She learnt English, she had girlfriends there. But then it was necessary to come back and take over the business from grandfather, and my father, like a good son, obeyed,” said the artist in 2020.

They returned in 1933. Two years later, their son was born.

“I could have been an American. And so it happened that I am a Kysuce local,” Cipár noted.

Eighty-five years ago, Kysuce was one of the poorest parts of Czechoslovakia, but the Cipár family, unlike others, did not experience the harsh consequences of the world crisis thanks to their store. The original cottage in the community of Semeteš still stands and even today there is a shop and a tavern for tourists. The artist was born in the back room. The hard life in a remote area at the time, without electricity and running water, was balanced by beautiful memories of old days and nature.

“Childhood in Kysuce was a happy, idyllic time. My father was full of strength, my mother sang at home,” Cipár recalled last year, adding that it did not last long.

Mobilisation, disintegration of Czechoslovakia, and the Second World War soon followed. After the war, Communists usurped power. Cipár’s father was a Democrat, so he was made enemy of the nation. His business was nationalised. He remained a salesperson - in his own shop, which the Communists took from him.

“This was a major injustice that we suffered. It deeply affected my father and the whole family,” the artist said.

Even in this forgotten region, the little boy perceived huge changes on the European map through his child’s eyes. At the beginning of the war, German soldiers attacked Poland from the then territory of Slovakia and started the war. The soldiers smoked in the grass, wearing new uniforms, and children collected cigarettes and chocolate after they left.

A few years later, other soldiers arrived. They were tired, dirty and muddy, and they drove red-star tanks straight across people’s fences and gardens. Meanwhile, the partisans and pseudo-partisans who roamed the Kysuce hills looted cottages with stolen rifles.

Tragedy at the end of the war

At the very end of the war, 75 years ago, when the world was already looking forward to peace, tragedy was about to hit Semeteš.

On April 20, 1945, the Vlasovs, Russian anti-Bolshevik soldiers who fought in the war on the side of the Nazis, arrived in the community. They plundered and set fire to cottages, women and children wept, and the soldiers led all the boys and men away from the community. Some were only sixteen years old. The Vlasovs were furious. They wanted revenge for a mine that had just exploded under one of their cars. It had been placed under the vehicle by the Kysuce pseudo-partisans, who fled to the forest and left people in Semeteš to their fate.

The boys and men were the first to be taken to the town of Turzovka, where the Gestapo office was located, but then a new order came, and the soldiers gathered them in the middle of the road. Two soldiers started shooting them. Somehow, by chance, they did not hit salesperson and tavern owner Štefan Cipár, who fell to the ground in self-preservation, pretending to be dead.

“I could hear the machine gun shots.” The artist recalled his father’s words: “'Everyone had fallen around me. When I saw that I was the only one standing, I quickly fell among them.'” However, to make sure the lying bodies were dead, the soldiers shot bullets into their heads. Štefan Cipár was incredibly lucky for the second time: the bullet flew through the back of his head and came out his nose.

When all went quiet, he started to crawl across the stream and to a cottage on the hill. He could not see through one eye. At the fence, his son noticed him. At first, he did not even recognise his father as he was swollen and covered in blood. There was no medicine, and they could not bandage his wound so that he would not bleed internally.

His father was saved and cared for by two refugees, one doctor a fugitive and the other a Jew. In the end, at an advanced age, Štefan Cipár even lived to see the fall of communism, which had robbed him of his shop.

A few days after the terrible massacre, ten-year-old Miroslav Cipár took an admission test to a grammar school in Žilina.

Hundreds of books

Cipár said his parents had always supported him in his decision to become an artist, probably also because they had seen the world and not just life in a hamlet.

We often go into despair; it seems to us that the world is corrupt, evil, hostile, that chaos reigns. We lose hope and no answer comes when we ask: is it chaos or the natural state of the world? However, it is possible to get, slip, even paint our way out of tricky situations. Those able do it are happy.“

He made the decision about his future while studying in grammar school. Later he studied graphics and monumental painting, which was then applied in architecture. Yet he did not pursue this form of art. He was discouraged by the corruption, the extent of which has not changed, and it was perhaps even more shameful back then.

Cipár soon began to illustrate in addition to creating his own artworks. He established himself in publishing houses such as Mladé letá; he co-founded the Biennial of Illustrations and other cultural projects.

“Art historians struggle to categorise me, they have a demanding time sorting my work because I always use a different technique,” the artist said last year. “But I like to try new things. Even in children’s literature, I have often changed techniques.”

Generations have grown up on books with his illustrations, and they are still popular among children. Princesses, castles, dragons and animals, illustrating hundreds of books before his death. He also illustrated major works of world literature: Giovanni Boccacci’s Decameron, François Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, Faust and TheSong of Songs.

Fall of communism

Cipár perceived what the Communists had once done to his father as something he could not influence or correct. The opportunity finally came, and he was present.

Although the faces of November 1989 are well known today, others also took part in the revolutionary events that year.

On Friday, November 17, Communist police officers beat students at a demonstration. On Sunday, November 19, a manifesto was penned, the first document of the Velvet Revolution in Slovakia. A group of artists wrote it at Cipár’s home on Sunday morning.

“We are protesting against the hypocritical game of democracy,” they wrote. “We demand a cleansing of public life of Stalinist elements and methods.”

They called friends and met at the Umelecká beseda building in Bratislava at the first meeting of a civic movement that later overthrew the forty-year-old regime. It was not crowds at the time, just a few hundred people, and there were almost as many members of the secret police.

So why was Miroslav Cipár never one of the faces of November 1989, when he co-founded the Public Against Violence? “I'm not a leader, nor the type who pushes himself to the front row when being photographed,” Cipár said in 2020.

He added that several future personalities had preferred to hide from the cameras because everything had been uncertain at the time. “We occupied the square, but we could still have ended up in Februárka (today’s police building on Račianska Street in Bratislava, then the State Security Headquarters). We had originally planned to do something on December 10, Day of Human Rights, so when the November events occurred, we were able to respond,” the artist recalled.

And how did he perceive the skepticism that kept spreading in society more than thirty years after the fall of the freedom-strangling regime?

“It has always been like that,” he noted last year. “People have a lack of information or, conversely, an abundance of information, but insufficient. Many do not understand or do not want to understand that democracy is a process and still evolving.”

He continued: “The philosophers of ancient times strived for an ideal state. In a Kysuce tavern I once heard a man say: the one who wants to rule is a swine. But it is not true that nothing has improved. Our society is not stagnating, and we have moved on from the place we were at thirty years ago.”

Between silence and a scream

In Cipár's studio, older and newer works still lean against the walls. Acrylic paints and a palette on the table.

“I'm old school,” he used to say.

In fact, he always used and combined classical methods with modern ones. He has long been called one of Slovakia’s most versatile artists. In addition to illustrations, he also devoted himself to graphic design, creating hundreds of assorted brands, pictograms and well-known logos, including logos for the Slovak National Gallery and the Bratislavské hudobné slávnosti festival. He donated more than five thousand of his drawings, designs and illustrations to the Bratislava Museum of Design.

It is not true that nothing has improved. Our society is not stagnating, and we have moved on from the place we were at thirty years ago.“

“A good logotype is like math, music and poetry,” Cipár once said. “As an artist, I have to discipline myself to create the perfect logo. And then, I have to make sure it works.”

His third interest was painting. The entanglements of lines often reveal humorous but also more serious motifs. Neither did he avoid the past of his ancestors in his paintings: for example, when the shape of a wire shopping cart from supermarkets, which was once invented by Slovak wiremen, emerges from doodles.

“My life is doodled like my paintings,” Cipár said a year ago. “Free production, for me, means bridging the barrier between spontaneous painting and graphic design. There is a duel, a battle with one other, happening in my paintings. Emotions can be manifested everywhere, even in calligraphy. It is something between silence and a scream.”

The Slovak artist had kept himself busy until his final days, working on exhibitions and new book illustrations, and he always believed people could turn bad days into good ones.

“We often go into despair, it seems to us that the world is corrupt, evil, hostile, that chaos reigns. We lose hope and no answer comes when we ask: is it chaos or the natural state of the world? However, it is possible to get, slip, even paint our way out of tricky situations. Those able do it are happy.”

© Sme

Painter and illustrator Miroslav Cipár died at the age of 86 on November 8, 2021. (source: Marko Erd)

Painter and illustrator Miroslav Cipár died at the age of 86 on November 8, 2021. (source: Marko Erd)

Miroslav Cipár's parents in NYC. (source: Archives of Miroslav Cipár)

Miroslav Cipár's parents in NYC. (source: Archives of Miroslav Cipár)

Miroslav Cipár's father almost lost his life during the Semeteš Massacre. (source: Archives of Miroslav Cipár)

Miroslav Cipár's father almost lost his life during the Semeteš Massacre. (source: Archives of Miroslav Cipár)

Miroslav Cipár. (source: Marko Erd)

Miroslav Cipár. (source: Marko Erd)