Zimbabwean Brian Jakubec was on a sightseeing trip to the Moravian capital of Brno, Czech Republic, after the first coronavirus wave, in 2020, when he sensed that he was back home.

“At that stage I wasn’t Czech, and definitely wasn’t Slovak, but I thought, ‘If my dad’s looking down at me right now, I’m right in the heart of his home country,” the 66-year-old Jakubec recalls over a cup of coffee in a Bratislava bookshop. “As I say, finishing off what he started.”

Born in 1916, Jakubec’s father, František, was brought up with his six siblings by their widowed mother in eastern Bohemia in Czechoslovakia. Coming from a poor family, the teenage František was accepted for studies at the Baťa School of Work in the eastern Moravian town of Zlín. The boarding school offered in-house education and training for future employees of the widely-known Baťa footwear manufacturer; Czech entrepreneur Tomáš Baťa had founded the global firm in Zlín at the end of the 19th century. At school, František’s day had a strict daily routine: a group exercise shortly after 5:30, paid work from 7:00 to 19:00, with a two-hour break; study from 18:00 until 21:00; bedtime at 21:30. Jakubec’s father worked different jobs at the Baťa firm. In 1939, after eight years spent in Zlín, he moved to Kenya, then a British colony, where he helped expand the Baťa business. A few years later, he relocated to the then British colony of Rhodesia, now independent Zimbabwe, to work as chief accountant for Baťa. Towards the end of his career, the firm asked him to help establish another new factory in South Africa.

“In some ways, Baťa was buying loyalty because he was targeting poorer families to find employees,” Jakubec explains. Baťa workers earned more than the going salary in each region, and shoemakers could often earn more than managers if they worked long hours and improved their skills. This was yet another way, in addition to education and training, that Baťa aimed to build a strong bond between his workers and his firm. “It was a profit-sharing scheme that he introduced a hundred years ago, which in my mind is really remarkable.”

Jakubec’s two older brothers followed in their father’s shoes and worked for the Baťa firm in several African countries, but not Brian himself.

“I was a little bit of a rebel,” he admits.

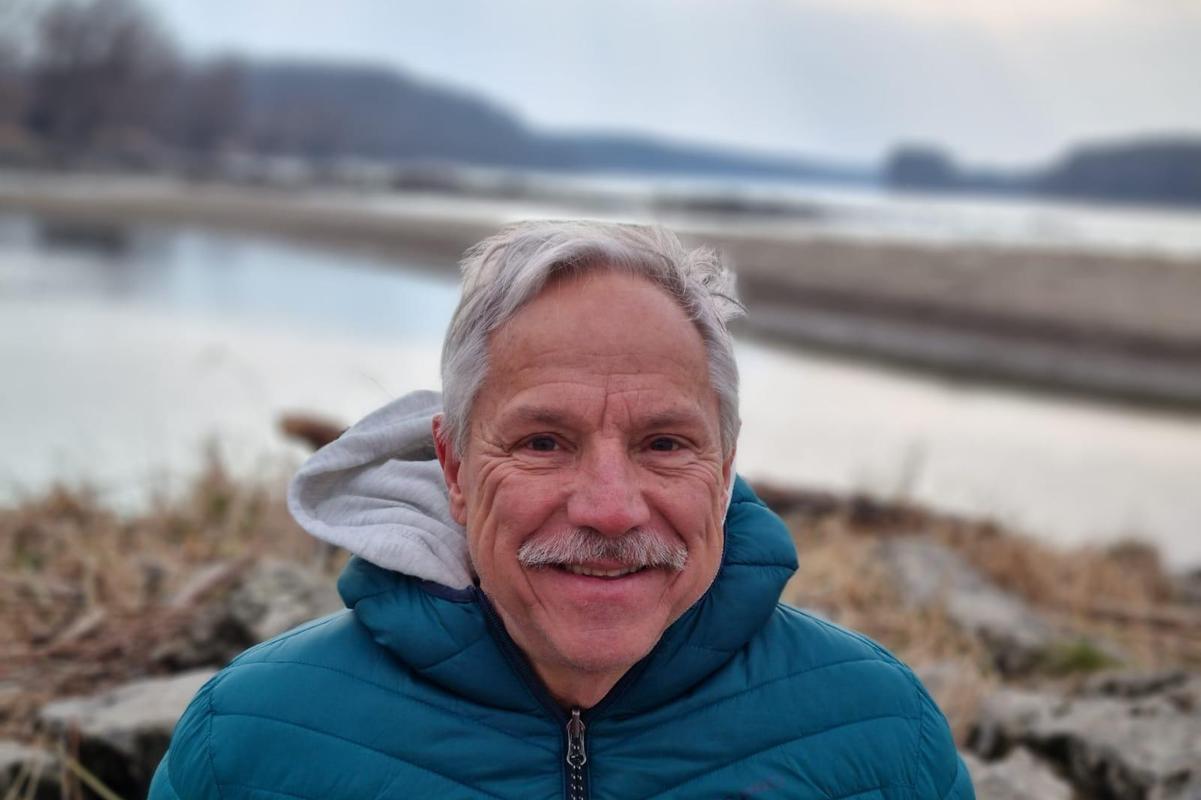

Brian Jakubec. (source: Archive of B.J.)

Brian Jakubec. (source: Archive of B.J.)