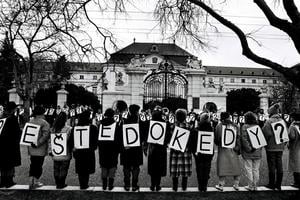

The new sense of freedom was powerful and formative. Everyone felt better, standing in the cold November squares. “We are not like them,” the crowd chanted, and even those who had been silent for years or had reported their neighbours for listening to Radio Free Europe, meant it.

Those were the days when we all found a version of a better society within us.

>>> Click here for more stories about the Velvet Revolution

Democracy was fragile and it required constant care to make sure it did not squint, or develop flat feet or a crooked back. Nobody knew in 1993 if it was ready to bear the illnesses that the founders of the state had smuggled into the new Slovak Republic from the old regime under the cover of the roar of the New Year fireworks.

It was a nation born after the break-up of Czechoslovakia by the winners of democratic elections as an answer to the questions that nobody asked the nation in a referendum.

And in its cradle lurked a tradition that was yet to take on monstrous dimensions, a tradition that says, ‘it’s after the election, get used to it’ or ‘win elections and you can do anything’.

Metamorphoses of freedom

Not everyone consumed freedom in the same way. Not everyone was one of the lucky ones, the generation of Husak’s children, born in the 1970s, who could cross borders and go to foreign universities to wash off the sediments of the communist schooling system.

(source: TASR)

(source: TASR)