“Now it feels real,” says Cande Glikin, a young Argentinian who recently reclaimed her Slovak citizenship. But this wasn’t just paperwork – it was the closing of a century-long loop, a return to roots once severed by oceans, war, and time.

Just weeks ago, she stood in front of a modest home in the village of Častá, nestled in the rolling hills near the Little Carpathians of Slovakia. It was the very house where her grandfather had once lived before leaving everything behind in search of a better life across the ocean.

“This [citizenship] process gave me not only the right to be in the EU and everything that comes with it, but also the drive and resources to find information about my ancestors, which I have been trying to do since I was little,” she reflects. “This month I found the house where my grandfather used to live in Častá, and I went to see it. [I was] mind-blown.”

Cande’s story is more than touching – it is emblematic of a broader, often forgotten chapter in Slovak history: the great migration of Slovaks not just to the United States, but also to South America.

A new Slovak trail to the southern hemisphere

For decades, America stood as the ultimate beacon for Slovak migrants – a land of steel mills, coal mines, and unspoken promise of wealth. By 1910, nearly three-quarters of a million Slovaks had crossed the Atlantic, carving out new lives in bustling industrial cities like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Chicago. These migrants were not just chasing personal dreams – they were laying the foundations for one of the largest and most vibrant European diasporas in the world, second only to the Irish in per-capita terms.

But the tides of history shifted.

After World War I, amid growing fears of foreign influence and racial “degeneration,” the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, a seismic policy shift that introduced national-origin quotas. The law was designed explicitly to curb the arrival of the “masses” from southern and eastern Europe – Slavs, Italians, and Jews – whom many American policymakers feared were not integrating into the fabric of American society.

Since the turn of the 20th century, ethnic enclaves were rapidly growing – tight-knit neighborhoods where immigrants lived, worked, prayed, and socialized almost exclusively among their own. Slovaks, like many others, often didn’t speak English fluently – if at all – and many saw no reason to learn. For them, America was not a final destination. It was a means to an end.

The true aspiration wasn’t long-term settlement – it was to make money, send it home, and eventually return to the “Old Country.” Back then, the goal was to accumulate the mythical “golden $1,000”, enough to go back to Slovakia a rich farmer, able to buy land and livestock.

To the American political elite, this pattern was alarming. These migrants were seen not as future Americans, but as foreigners with one foot in – and the other foot out. The 1924 Immigration Act wasn’t just about restricting numbers – it was about reasserting control over national identity and forcing a pause in mass migration.

By slowing the influx of new arrivals, the 1924 quotas created space – intentionally or not – for the millions of Slavic migrants already in the United States to integrate more fully: to learn the language, adapt to American values, and participate in civic life.

But for Slovaks who suddenly found themselves shut out of the American dream, the journey didn’t end. It simply shifted course.

A new chapter began – not in the United States, but in the Global South.

Argentina: the new America for Slovaks

While the U.S. was building walls, Argentina was building bridges.

Determined to populate its vast interior and expand its industrial workforce, the Argentine government actively courted European migrants. It offered land, subsidized transport, and the promise of a new beginning – exactly what Slovaks had once sought in America.

Between the 1920s and 1930s, tens of thousands of Slovaks seized this opportunity. They came from familiar Slovak regions of emigration – Orava, Liptov, Spiš – but this time they docked not in New York, but in Buenos Aires, Rosario, Mendoza.

In total, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Slovaks made Argentina their new home, forging the largest Slovak community in South America.

Planting new roots in Latin soil

What emerged wasn’t just survival – it was cultural rebirth. Slovaks in Argentina preserved their traditions with incredible tenacity. Like in the United States, they built churches and schools, published Slovak-language newspapers (more than 20 in Buenos Aires alone), and raised children who grew up speaking the tongue of their ancestors in a land an ocean away from Europe.

The shift to Argentina was not accidental – it was born from geopolitical exclusion. But it became more than a detour. It was a transformation. It proved that where doors close, new paths open.

Just like Cande Glikin, many descendants of these migrants still carry the Slovak spirit within them – and some, a century later, are finding their way back home to their ancestral homeland.

From quotas to walls: echoes of 1924 in today’s America

Fast forward a century, and the story feels eerily familiar.

In the 2020s, the United States once again confronted a surge of migrants – this time not from Europe, but from the Global South, with the vast majority being illegal. Under Donald Trump’s administration, the country embarked on one of the most aggressive immigration crackdowns in modern history.

While the Great Migration from Europe differs from today’s influx across the southern U.S. border, it’s striking to see how history echoes itself. Back in 1924, the immigrant quota system was justified as a means of protecting American identity from the perceived threat of “masses” of Slavs, Italians, and Jews – newcomers accused of arriving without integrating. A century later, that same role of the outsider has been assigned to Mexicans and Central Americans.

These are the new arrivals whose growing presence the government is once again eager to limit – calling not only for stricter controls, but even for a so-called “pause” in migration. The rationale? To slow the flow and give those already here more time and space to adjust, integrate, and become part of American life.

Who belongs in America? And is hitting “pause” warranted?

America was not just built by immigrants – it was built by waves of immigrants who were each, in their time, treated as outsiders. The Irish were called drunkards. The Italians were suspected of anarchism. The Slovaks were once branded uneducated peasants from the “backward” Austro-Hungarian hinterlands.

Each of these groups fought for dignity. They worked hard, raised families, paid taxes, and eventually found a place in the American tapestry. Over time, they stopped being “others” and started being “American.”

But that transformation took time. And it came at a cost: name changes, forgotten languages, and severed ties with the old country.

Conclusion: the Slavic mirror

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

A century ago, Slovaks arrived in America as strangers – peasants from a distant empire, speaking foreign tongues, dreaming not of assimilation but of return. Then came 1924. The door slammed shut. Migration halted. And for those already inside, the pause forced a choice: stay and integrate into the United States – or return to the old land.

Ironically, that stillness may have forged something lasting. Over time, those transient laborers became Slovak Americans. They built churches, ran businesses, raised English-speaking children, and found their place in the American story. The pause gave space for transformation.

But not all Slovaks were given that chance. For the tens of thousands locked out of the “American Dream,” their journey simply shifted – to Argentina, where they planted new roots, carried on old traditions, and built a vibrant Slovak identity – this time on Latin American soil.

Today, descendants like Cande Glikin are tracing those paths in reverse – returning not just to Slovakia, but to a forgotten chapter of their own identity.

Cande Glikin in Argentina - in the beautiful Bariloche (Patagonia) region (source: Courtesy, Cande Glikin)

Cande Glikin in Argentina - in the beautiful Bariloche (Patagonia) region (source: Courtesy, Cande Glikin)

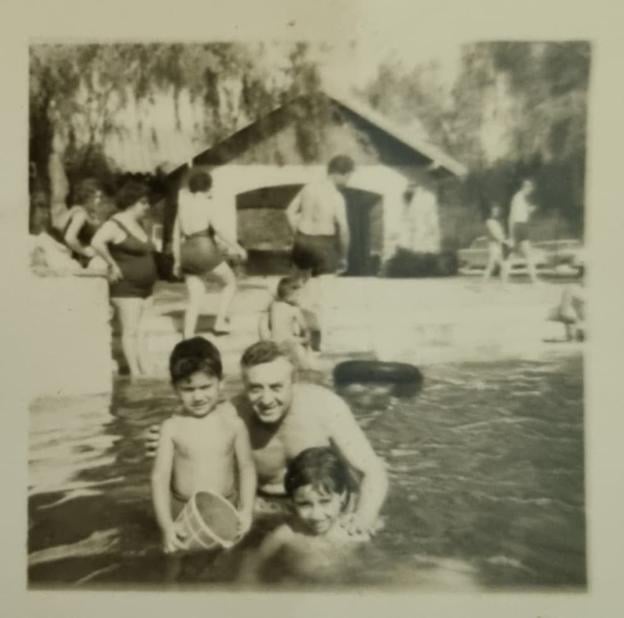

Cande Glikin’s Slovak grandfather, Eugen, in Argentina with his children (source: Courtesy, Cande Glikin)

Cande Glikin’s Slovak grandfather, Eugen, in Argentina with his children (source: Courtesy, Cande Glikin)

Cande Glikin’ Slovak grandfather Eugen in Argentina (source: Courtesy, Cande Glikin)

Cande Glikin’ Slovak grandfather Eugen in Argentina (source: Courtesy, Cande Glikin)