Komárno, a town on the Danube in southern Slovakia, is locked in a battle against a new casino being planned on its outskirts – a project that local officials say threatens its image and development strategy, Denník N reported.

The surge of casinos in the region has its roots in Hungary, where Viktor Orbán’s government banned slot machines in pubs in 2012 and introduced a strict concession system. Many Hungarian players simply crossed into Slovakia, where regulation of gambling remains looser and the state lacks a clear long-term strategy.

While slot machines are banned in Slovak pubs, licensing is overseen by the Gambling Regulation Office (ÚRHH). Since 2019, the office has granted nearly all licence requests: between 2022 and 2024 it approved 211 out of 212 applications, according to the Supreme Audit Office. No licences were revoked during this period, despite violations being identified.

Komárno’s local struggle

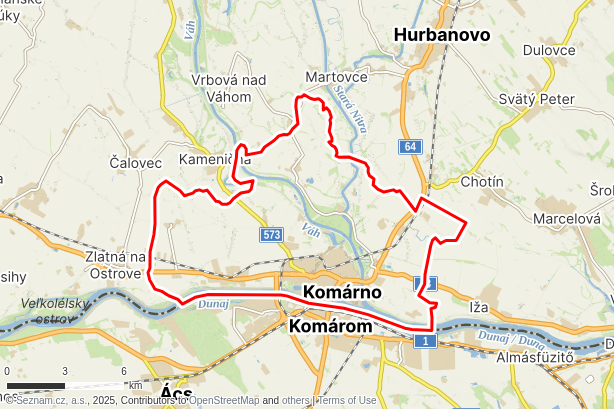

Komárno, which is already home to one casino and dozens of slot-machine halls, has tried to curb gambling by requiring venues to be at least 200 metres apart. Yet the town has failed to prevent approval of a new casino on the site of a former customs office directly next to the border crossing with Hungary.

The mayor of Komárno, Béla Keszegh, argues that the project undermines public interest and tourism development. However, the ÚRHH dismissed the city’s objections as too general, while prosecutors warned the municipality against “arbitrary” reasoning.

The dispute highlights a broader policy dilemma. A full ban, Keszegh says, would only push gamblers to neighbouring towns or to unregulated online platforms. At the same time, municipalities receive less revenue from land-based gambling each year – their share fell from €21 million in 2018 to €13 million in 2024 – while online casinos, which do not attract local taxes, are booming.

National policy battles

National politics further complicate the issue. As part of fiscal consolidation, Finance Minister Ladislav Kamenický may fold the ÚRHH into his ministry. At the same time, Tourism and Sport Minister Rudolf Huliak and Environment Minister Tomáš Taraba are clashing over taxation: Huliak favours a 21-percent levy on land-based casinos, warning that higher rates would drive gamblers underground, while Taraba is calling for a 30-percent tax to match online gambling.

Huliak has also floated plans to expand the state-owned Tipos lottery company into land-based casinos, sidelining municipalities entirely. Critics fear this would deepen Slovakia’s reputation as a “gambling haven” along the Danube.

For now, Komárno’s leaders say they only want more control: the ability to define no-go zones near schools, cultural sites or central squares. As Keszegh puts it, “Casinos may have their place – but not as the first thing visitors see when they enter our city.”

Casino gambling (source: TASR/AP Photo/Chitose Suzuki )

Casino gambling (source: TASR/AP Photo/Chitose Suzuki )