This story was produced in partnership withReporting Democracy, a cross-border journalism platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

After parliament in 2017 elected university professor Mária Patakyová, Slovakia’s third public defender of rights (PDOR or ombudsman), she expressed her hope that the public administration and politicians would show more respect to the office that she was about to represent.

“I hope they will realise that what the public defender of rights does is actually a good service for them,” she said.

Yet five years later, in late March 2022, Patakyová found herself standing at a lectern in parliament presenting her final annual report before the end of her term with only a handful of lawmakers in attendance – a practice that had become a tradition long before her appointment.

Her predecessor, the former judge Jana Dubovcová, faced the same ordeal. In 2014, just 11 out of the 150 lawmakers listened to her full speech.

“I didn’t feel good about it,” she confessed at the time. “It wasn’t some routine report, but a document in which I summed up the state of human rights in Slovakia.”

The Office of the Public Defender of Rights is the highest independent authority in the country that assesses whether public administration bodies have violated the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural or legal persons through their activities or inaction.

However, since Patakyová’s departure five months ago and with no successor in sight, the Office of the PDOR has been paralysed for the first time in its short history. As a condition set by the EU before Slovakia’s admission to the bloc in 2004, parliament established the authority 20 years ago.

“Still, our legislators apparently are not too enthusiastic about the existence of the Office of the Public Defender of Rights,” said Via Iuris, a group advocating for the protection of the rule of law.

The names of several potential candidates who might succeed Patakyová as PDOR have appeared in the media, but the coalition parties, subsumed by a political crisis that has reduced their number from four to three, have not agreed on one name to date.

Seven months without ombudsman

Patakyová had taken care of all the cases on her desk by the time she left the post, but today the cases waiting to be studied, decided and signed off on by the next PDOR are piling up. The number of pending files exceeds 400, according to the Office of the PDOR.

“The current situation is very disturbing, because it goes against the rights of those who have turned to the public defender,” Patakyová told Slovakia’s JOJ television channel in August.

Legislation currently does not allow the departing PDOR to stay in office up until the time that their successor is appointed. Though it would not help tackle the current crisis, SaS MP Vladimíra Marcinková and her colleagues have set out to change that and submitted a constitutional change to the parliament at the end of August.

“Harvesting 90 votes for the change will be a small referendum on how much the protection of human rights matters to lawmakers,” Marcinková said. Parliament should vote on the amendment in September.

Unlike other parties, SaS, a liberal and mildly Eurosceptic party, has actually got around to choosing a candidate it intends to nominate for the post, in this case Marián Török, a chief of staff at the Office of the PDOR under Dubovcová and Patakyová.

The vote on the new PDOR in parliament should take place in mid-October after Speaker of Parliament Boris Kollár postponed the deadline for the submission of candidates four times, most recently to the end of September.

“This decision shows the absolute disinterest of politicians in the protection of human rights, even if they like to claim otherwise,” said Via Iuris.

The organisation called Kollár’s move irresponsible.

Help from an underfunded Office

Unlike most political parties in parliament that have appeared to not consider the election of the new public defender as a top priority, the Office of the PDOR cautions that dozens of cases are pressing.

One such case concerns a prisoner convicted to five years in jail, during which they were ordered to undergo institutional drug treatment so they could return to normal life as soon as possible afterwards. Yet the convict was not sent for any drug treatment during that five years, meaning they will most likely have to do it despite their release from prison.

“If the court does not change the prescribed form of treatment – institutional – the person will simply continue to be confined in a hospital facility,” explained the Office of the PDOR’s home and international affairs adviser Júlia Šebová. Were the PDOR elected, they could step in, she added.

The PDOR in Slovakia can control, notify and suggest proposals to public administration bodies to fix a situation in which they have violated a person’s rights. It can also turn to the Constitutional Court.

“The urgency in these cases [sent to the Constitutional Court] is all the greater because, unlike the ‘individual failure of a state body’, unconstitutional legislation affects all addressees of the legal norm,” Šebová pointed out.

In Brussels, the European Commission noted that Slovakia has not elected its next PDOR. In its “Rule of Law Report”, the Commission also wrote that the country’s independent body is underfunded and understaffed.

It is the Finance Ministry that approves the budget for the PDOR, which successive previous holders of the office have unsuccessfully tried to change. The government, moreover, approves the maximum number of employees working for the PDOR. The limit is set at 52 today, but the office currently only employs 40 people due to financial constraints.

The Office of the PDOR also for a long time suffered from a lack of a base. Pavel Kandráč, the first PDOR elected in 2002, officiated from parliament at the outset. It took the state 12 years to assign a building to the Office of the PDOR, which had been forced to pay expensive rents to a private firm for several years.

Government and public defender clash over Roma issue

Over the years, the PDOR has grown into an institution that is certainly seen, but one that still lacks respect.

“The beginnings weren’t easy, not just for us but also for various institutions,” Kandráč told Slovenské Národné Noviny, a conservative biweekly, last year. “Many considered us to be a kind of superior office and were worried they would be pushed about.”

Kandráč was a lawmaker for HZDS, an opposition party led by the authoritarian ex-prime minister Vladimír Mečiar, when he was elected as the PDOR by parliament following the coalition’s failure to jointly vote for its candidate. His victory dissatisfied non-governmental organisations that supported lawyer Ján Hrubala, now a chief justice at the Specialised Criminal Court.

In 2007, as a candidate of the then Smer-led ruling coalition that HZDS was part of, Kandráč was re-elected to the office. He chiefly dealt with cases that concerned lengthy court proceedings.

As the only candidate, Dubovcová replaced Kandráč in 2012. A former judge who was a critic of how things worked in the judiciary and an ex-MP for the then-ruling party SDKÚ, experts and politicians in power praised her election. Yet the opposition disapproved of the ex-judge.

“It’s a very bad choice,” said Smer’s party leader Robert Fico, who a few days after Dubovcová’s appointment became prime minister. He remained in power until 2018.

Unlike her predecessor, Dubovcová began to draw attention to the violation of children’s rights in secure training centres; to deficiencies in the approach of educating Roma children and children with special needs; to the worsening availability of social services for the elderly; to the lack of barrier-free access to public administration buildings; as well as to the many shortcomings in how the Foreigners’ Police dealt with immigrants after their arrival in Slovakia.

When she flagged and condemned a 2013 police raid in Budulovská, a Roma settlement in eastern Slovakia, Dubovcová suffered a backlash from Fico’s government.

The brutal police search carried out by more than 60 armed officers was unnecessary, inadequate and violated people’s rights, Dubovcová wrote in one of her annual reports. Conversely, the police inspectorate under the Interior Ministry, which was then led by Robert Kaliňák of Smer, saw nothing wrong with the raid. In contrast to any police officers, several Roma people were charged with perjury.

“Dubovcová defends people who have broken the law, lies and threatens the police,” Kaliňák said after a January 2014 government meeting attended by the PDOR. At the meeting she was meant to discuss her August 2013 special report on the violation of the Roma minority’s rights by the public administration, including the police, but the government did not allow her to speak.

Following a 2020 European Court of Human Rights judgement, Slovakia publicly apologised for the Budulovská raid in 2021. The charges were dropped against the Roma individuals.

However, unlike Dubovcová’s annual reports, she never had an opportunity to present her special report from 2013 to parliament. When she came to parliament with her second special report, in 2016, criticising the police for placing detained persons in illegal premises instead of in police custody cells, legislators did not support her report in a vote. Lawmakers also rejected her 2017 special report in which she drew attention to the violation of children’s rights in addiction treatment facilities and children’s homes.

“We are still at the point where the authorities do not like to hear criticism,” Dubovcová said a few months before leaving her post.

Even so, during the Office of the PDOR’s 20 years in existence, it has received 39,217 complaints from people.

Criticism of rainbow flags

After Patakyová took office as the new PDOR in 2017, several things changed. Yet legislators’ ignorance of the PDOR’s annual reports in the parliamentary chamber was not one of them.

Apart from Dubovcová’s agenda, Patakyová drew attention to the rights of new mothers and the forced sterilisation of Roma women – a practice for which Slovakia had been criticised by the UN for years. Slovakia apologised to the affected women last year.

The current and largely conservative parliament rejected two of Patakyová’s annual reports. In the 2019 and 2020 reports, she highlighted the violation of people’s rights during the COVID-19 pandemic and condemned attempts to introduce stricter abortion laws.

Moreover, conservative MPs repeatedly criticised the last two PDORs for their support of the LGBT community and for placing a rainbow flag outside their office.

“The Office of the Public of Defender of Rights does not belong to the LGBT+ community,” the Slovak National Party, one of the ruling parties in the years 2016-2020, told Patakyová several months after she was appointed.

Patakyová did not feel discouraged and regularly emphasised how Slovakia does not have any legislation that would recognise civil unions or gay marriage. One of the very last things that she did was to turn to the Constitutional Court over the police’s failure to grant permanent residence to a gay New Zealander married to a Slovak.

“During my five-year term, I was guided by the effort to amplify the voice of those whose problems were overlooked by public power,” she said in her last Facebook post as the PDOR.

Public Defender of Rights Mária Patakyová left her office on March 29, 2022. (source: Sme - Marko Erd)

Public Defender of Rights Mária Patakyová left her office on March 29, 2022. (source: Sme - Marko Erd)

Jana Dubovcová speaks to MPs a month before her term as the public defender of rights ends in March 2017. (source: TASR - Michal Svítok)

Jana Dubovcová speaks to MPs a month before her term as the public defender of rights ends in March 2017. (source: TASR - Michal Svítok)

SaS MP Vladimíra Marcinková announces in late August 2022 that her colleagues and she have put forward a proposal to change the constitution. The change concerns the public defender of rights. (source: Facebook/Vladimíra Marcinková)

SaS MP Vladimíra Marcinková announces in late August 2022 that her colleagues and she have put forward a proposal to change the constitution. The change concerns the public defender of rights. (source: Facebook/Vladimíra Marcinková)

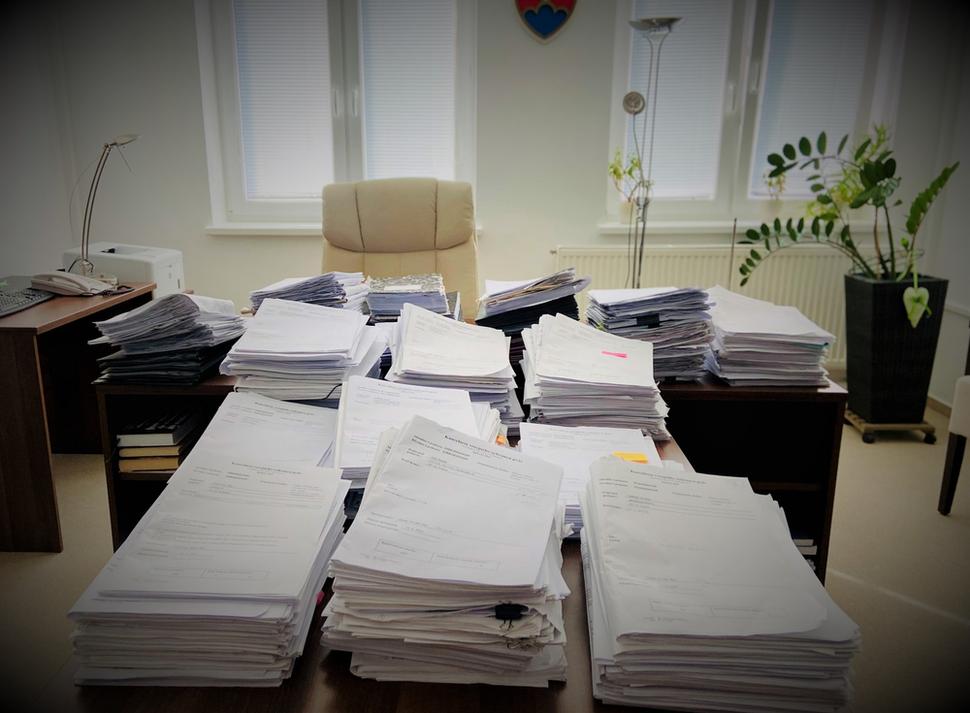

The new public defender of rights will have to go through almost 500 new case files that have landed on their table by early September 2022. (source: Facebook/Verejný ochranca práv)

The new public defender of rights will have to go through almost 500 new case files that have landed on their table by early September 2022. (source: Facebook/Verejný ochranca práv)

Public Defender of Rights Jana Dubovcová reads her first special report in parliament on December 8, 2016. (source: TASR - Andrej Galica)

Public Defender of Rights Jana Dubovcová reads her first special report in parliament on December 8, 2016. (source: TASR - Andrej Galica)

Public Defender of Rights Mária Patakyová is pictured during her speech at the Rainbow PRIDE Bratislava 2018 Festival on Hviezdoslav Square in Bratislava on July, 14 2018. (source: TASR - Martin Baumann)

Public Defender of Rights Mária Patakyová is pictured during her speech at the Rainbow PRIDE Bratislava 2018 Festival on Hviezdoslav Square in Bratislava on July, 14 2018. (source: TASR - Martin Baumann)