Small organic farms are scarce in Slovakia, a country where agriculture is still symbolised by a sector comprising mostly large-scale production.

Historically, Slovakia was the less industrialised and less modernised part of Czechoslovakia, but in the years that followed World War II it too went through the transition from agricultural through industrial to a service-oriented economy. Following those developments, Slovakia’s agricultural sector has experienced difficult years.

The main challenge is the lack of interest among young people in going into farming, coupled with climate change that shifts locations of cultivation, excessive yields of certain crops, a milk price crisis, foreign ownership of local land and low self-sufficiency in essential food products. Despite these dire circumstances agriculture experts see opportunities for Slovaks, mostly in organic farming, agro-tourism and specialised crop production.

“Companies which regularly fit in the top 100 agriculture companies or participate in the Najkrajší chotár (Most Beautiful Land Area) competition show evidence that they can produce even in the unflattering conditions of our agriculture,” Slovak Agriculture and Food Chamber (SPPK) spokeswoman Jana Holéciová told The Slovak Spectator.

Decline in performance

In 2016, production and revenues of the agriculture sector declined and only one-fifth of companies in the sector expect growth of their market share, the results of the survey of a research and analysis firm CEEC Research show.

While the average company’s utilisation was 83 percent in August 2016, pessimism arises primarily in livestock production, said Jiří Vacek, director of CEEC Research. The market is forecast to contract by 1.1 percent in 2017.

As a result of fewer livestock, milk production fell in 2007-2014 by 10.7 percent, beef by 25.4 percent and poultry by 12.1 percent. Though consumption of pork, beef and poultry also fell, the consumption of milk increased by 17.5 percent, according to Dagmar Matoušková of the Research Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics (VÚEPP).

While in 2005, there were 81,500 employees working in agriculture and 59,400 employees in the food industry, in 2014 the numbers stood at 51,500 and 50,200 employees, respectively. Between 1995 and 2014, the employment rate in the sector fell by 73 percent, according to SPPK statistics.

The fall comes amid a decline in agricultural production, transformation and dissolution of non-agricultural activities and subsequently the low diversification of activities, low work valuation and loss of manual work, Holéciová said. She explained that employment in agriculture depends on material and production efficiency, saving costs and potential to sell products on domestic or foreign markets.

Milk crisis affects the sector

Development in the sector is affected by frequent changes to EU subsidy programmes, which impacts consumer prices. Sanctions against Russia leading to a surplus of pork, record-breaking grain harvests and unresolved problem of milk prices are all factors, said Vacek.

“The market expects a large fall in sales due to overproduction,” Vacek said.

In 2016, Slovak dairy producers experienced milk crisis due to overproduction and low retail prices. To solve the crisis, the Agriculture Ministry decided to stabilise the sector, support employment in regions and acquire detailed data on dairy farming for a long-term strategy.

By late September, 1,760 of the total 2,692 dairy farmers had joined the medium-term project which involves payments to farmers and information gathering. The measure includes financial support of €33 million for primary milk products in 2016, of which €30 million will be provided by the Finance Ministry and €3 million from the Agriculture Ministry, said Prime Minister Robert Fico as he introduced the measure, as reported by the TASR newswire.

Targeting a new generation

But the milk crisis is not the sole problem the agriculture sector has to cope with. Generational replacement and lack of business structures that would meet the demand for specific regional products are among the longterm challenges listed by Jana Gasperová of the Agriculture Ministry.

Low interest in working in the sector among qualified youth is a problem that the chamber is aware of too, Holéciová confirmed. SPPK thereby welcomes the dual education system in which 33 agricultural and food companies educate students with the greatest interest in fields like farmer-mechanisation and pastry baking in the academic year 2016/2017.

Responding to the need to employ about 1,990 new people under 40 years of age in the sector, the ministry launched a project to support young farmers who are starting their own animal and crop production businesses. The basic measure of the project is a subsidy of €50,000.

Other measures include a state aid scheme for employment of disadvantaged persons, the European Social Fund for Employment, operating and investment loans for novices and nonrepayable financial aid of the 2014-2020 Rural Development Programme for Slovakia.

Local patriotism

The rural character of Slovakia well into the 20th century also meant that until just a few decades ago it was still common to see farm animals in every village backyard. Agricultural production was thus a natural part of people’s lives from a young age. Today, cows for personal use are rare and are mostly replaced by poultry, pigs, rabbits and bees, the ministry listed.

In the 1970s and 1990s the efforts of Slovak households in rural areas to sustain themselves from their own farming products were booming. People living in the countryside would produce home-made, healthy products for themselves and even for their children living in cities. They would breed poultry, rabbits, produce eggs, pork meat and lard, vegetables, potatoes, fruits, and other products, said VÚEPP analyst Mária Jamborová. In some cases they would even make money selling their overproduction to their neighbours or friends.

This created a significant “cushioning effect” in the society that tamed the social consequences of transformation and restructuring of the society, and also contributed to taming the big difference between living standards of people in cities and people in villages.

Some people are now returning to farming and breeding animals on their own land. Such regional products of high quality and safety guarantee that customers keep returning and do not prefer ordinary retailers, said Gasperová.

A strong feeling of belonging to the soil and respect to traditions is still present mostly among the rural population.

“That is why gardening still represents an important part of the life of people, despite the fact that the economic side of farming is no longer the most important,” Jamborová told The Slovak Spectator.

In 2013-2014, subsistence farmers participated in the total market of vegetable produce on average by almost 40 percent and in domestic consumption by 60 percent. The biggest share of subsistence farmers was in cabbage (24.1 percent), tomatoes (13.6 percent), carrots (11.6 percent), peppers (9.5 percent), onions (8 percent), cucumbers (6.3 percent), gherkins (5 percent), parsley (3.1 percent), kohlrabi (5.2 percent) and celery (0.6 percent), according to VÚEPP.

“Subsistence farmers less addressed cultivation of eggplants, beans, watermelons, red pumpkins and spinach, which apparently stems from the difficulty of growing them,” Jamborová said.

Foreign ownership in spotlight

With a large part of Slovak land under foreign ownership, former agriculture minister Ľubomír Jahnátek in 2014 adopted the Act on Acquisition of Property Right to Agricultural Land which required foreign buyers to be active in agricultural production for at least three years and have a residence permit in Slovakia valid for at least 10 years.

However, the European Commission (EC) criticised the rules as restricting free movement of capital and hindering the right to settle, which could discourage cross-border investment. The EC has forced Slovak authorities to amend the law and liberalise rules for foreigners acquiring land in Slovakia.

The draft amendment introduced in July 2016 abolishes the requirement of 10 years of residence permit to increase transparency, awareness of market offers and number of preventive actions against speculative buying of land for non-agricultural purposes, according to Gasperová.

“Other modifications may reduce the administrative burden and improve access of active farmers to the land,” Gasperová told The Slovak Spectator.

The residency period applied only to sales of land of more than 2,000 square metres situated outside an urban area. In Slovakia, there were a total of nearly 7,000 such areas outside and inside village areas by July 2016, the Sme daily reported.

In addition to the amendment, Agriculture Minister Gabriela Matečná announced that she would gather the relevant self-governing farmers’ organisations for a round-table on October 24, to discuss the possibilities of joint action in proposing constitutional solutions to the problem. She claims there are public concerns that Slovakia would become vulnerable to speculative land purchases and that the farmers’ organisations are calling for a constitutional amendment to prevent potential negative consequences.

Production structure alters

In comparison with crop planting in the past, farmers currently raise more durum wheat and shift corn production to more northern areas where they can take advantage of accumulated water during winter. Plant breeders point to a return to the Slovak breeds which are better at handling fluctuations in temperature and water deficit than the western-European ones, said Holéciová.

In the last two years, experts have recorded increases in soy-beans and partly in field pea, which are often used as renewable energy sources. Roman Hašana of the Research Institute of Plant Production (VÚRV) pointed out that plant types began to change in the restructuring of production after 1989 and since 2004 the sector has gradually lost its processing capacity.

“Ongoing processes of meteorological character which we can carefully call climate change do not significantly affect the structure of vegetable production in Slovakia,” Hašana told The Slovak Spectator.

Rare crops already include root vegetables and flax for fibre production. Hop-fields have been reduced and cultivation of tobacco is in retreat due to protection of public health. A further decrease is in fruits, vegetables and potatoes cultivated only on 8,066.15 hectares compared to 26,056.32 hectares in 2002, according to the ministry.

“We recorded a significant decrease also in legumes like lentils and beans which were gathered from historically lowest acreage of 60.4 hectares [in 2016] compared to 322 hectares in 2010,” Gasperová said.

Problems with surplus

The current unstable era and climate change bring fluctuations in harvested agricultural commodities. In 2016, Slovak farmers cropped around 3.2 million tonnes of grain, 2.3 million tonnes of which the country has to export due to low stocks of livestock and low consumption, according to SPPK.

“We have become exporters of raw material and import it back in the form of processed products, therefore, we do not produce added value in Slovakia but in other state,” Holéciová said.

In comparison with 2015, Slovakia produces 327,600 tonnes (11.4 percent) more of thicksown grains although acreage of sown land is less about 10,100 hectares (1.8 percent). Similarly, there are greater yields of seed corn by 522,600 tonnes (56.2 percent), potatoes by 49,600 tonnes (37.9 percent), silage corn by 708,900 tonnes (34.5 percent), sunflowers by 71,700 tonnes (41.1 percent) and sugar beet by 185,000 (15.3 percent). The Statistics Office (ŠÚSR) expects a fall in the barley and oats yield.

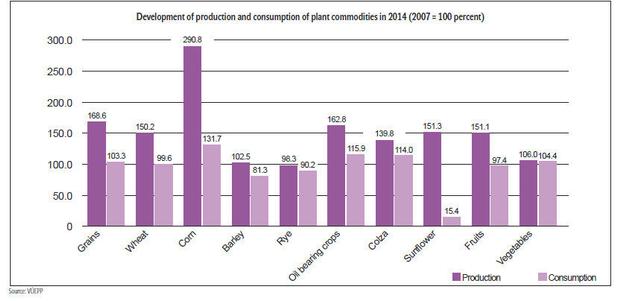

In 2007-2014, production of oil bearing crops jumped by 62.8 percent thanks to their increased use in energy and construction industries, Matoušková of VÚEPP noted.

Differences in self-sufficiency

The rate of self-sufficiency depends on volume of production and consumption, which should not be lower than 80 percent, said Matoušková. The indicator has worsened in milk and beef, although the beef sector is still more than self-sufficient (108.3 percent), and grains and oil bearing crops achieve positive results.

“We have also reached self-sufficiency in milk (89.1 percent) and poultry (93.4 percent) even though their domestic production has not fully covered their consumption,” Matoušková told The Slovak Spectator.

In addition, the country is self-sufficient in egg and sugar, of which products and consumes about 180,000 tonnes, according to SPPK. Selfsufficiency is not the case in pork sector where the production reaches now less than 50 percent of consumption.

The situation is alarming in fruits (66.1 percent) and vegetables (73.6 percent), Matoušková added.

How to be more independent

Vacek suggests better protection for domestic producers instead of companies which import goods into the country, re-package it and pretend they are “Slovak producers”. The future of food self-sufficiency is in the state hands and local patriotism, he said.

“People buy by price and there is a lack of national pride and education already in primary schools that purchasing Slovak products gives work to our own people,” Vacek said.

More village families breeding a few hens and rabbits or cultivating tomatoes and potatoes are desirable, said Holéciová.

“When a small child gets used to healthy home-made food, it will reach for more homemade Slovak products as an adult,” Holéciová said.

However, business-oriented farms and the trend towards professionalisation of groups of individual farmers have significantly accelerated, Jamborová said.

Government intervention

The current government in its programme statement pledged to develop production where authorities amend the regulation of dairy products in schools including selection of the product range, determination of the amount of the state aid and the highest charges paid by students.

There is also a target to promote free market development, where authorities have prepared a draft law on veterinary medicinal products and technical devices, plans to adopt the EU legislation of livestock breeding and increase support for sources of employment, Gasperová said.

“In 2015, the project of development of vegetable and livestock production and update of the register of orchards in relation to main types of apple and pear trees were implemented for the first time,” Gasperová said.

In addition, the Concept of Development of Slovak Agriculture for 2013–2020 aims to increase production of agricultural commodities to 80 percent of current consumption.

Illustrative stock photo (source: TASR)

Illustrative stock photo (source: TASR)

(source: Research Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics)

(source: Research Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics)