He knew that he wanted to leave Slovakia ever since he graduated from secondary school at the age of 20. “Leaving Slovakia wasn’t that much about hating something in Slovakia; it was more that I felt I will have a better education and more opportunities in Austria,” Kanka told The Slovak Spectator.

Slovakia witnesses the situation in which the number of people in productive age who left the country is higher than of those arriving. While most of them leave the country for an obvious reason – salary, the second biggest group is irritated by poorly run state.

While the Education Ministry is battling brain drain with grants for Slovaks graduating abroad, observers point out that without improving the economy there is little to be done to reverse the trend.

“Besides economic growth and prosperity in Slovakia, I don’t know the measure which could effectively draw people, who have decided to stay abroad, back to Slovakia,” sociologist Miroslav Bahna of the Institute for Sociology - Slovak Academy of Sciences (SAV) told The Slovak Spectator. “There is one solution used before 1989 – to close the borders.”

Interpreting statistics

The exact number of people who left Slovakia and do not plan to come back remains a mystery. It is impossible to count how many Slovaks left the country and what education they achieved, according to Vladimír Baláž, an economist at the Institute for Forecasting of the SAV.

“Our economy is harmed not only by those who leave the country with university-level education, meaning brain drain,” Baláž told The Slovak Spectator. “But also when a 30-year-old person with secondary-level education leaves because he or she could produce value, pay taxes here and contribute to the state welfare system.”

There are some studies that try to quantify the problem.

In 2014, more than 2,800 people left the country, about 17 more than the number who came. Thus for the first time in Slovak history the number of those leaving the country is higher than the number moving in. Moreover, the number of emigrants is the highest since 1993, since the establishment of the independent Slovak Republic, according to the data of the Demographic Research Centre (VDC).

The centre calculated the number from those who cancelled their permanent residence in Slovakia. The VDC data was published by the Financial Policy Institute (IFP).

However, the trend that saw Slovaks leave to go abroad was the greatest shortly after Slovakia joined the European Union in 2004, Bahna pointed out.

“In fact, instead of describing the current situation, this number says that some people who left the country in past decades are officially cancelling their residence in Slovakia with some delay,” Bahna said.

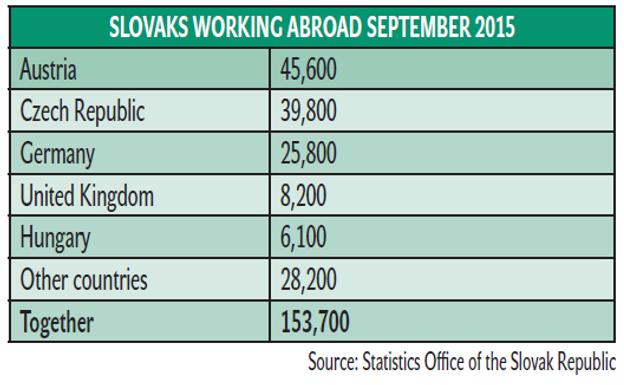

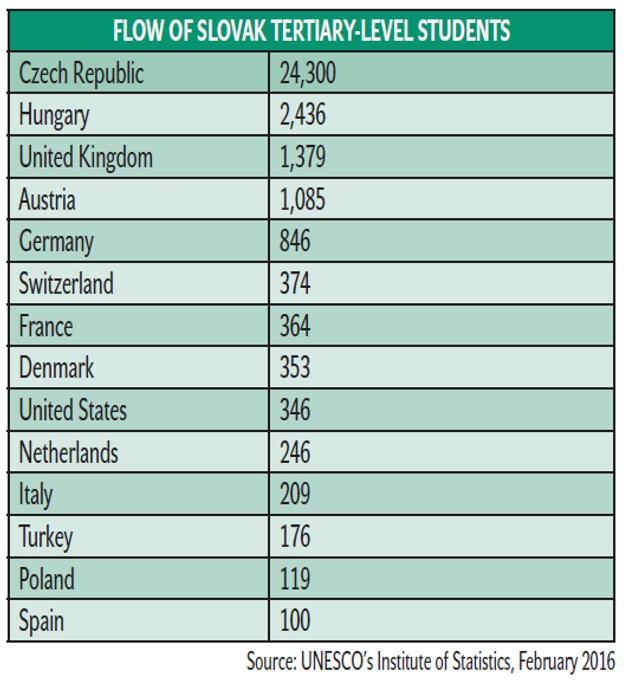

The Business Alliance of Slovakia (PAS) estimates that more than 300,000 Slovaks work abroad either short or long term, while additional about 30,000 Slovaks are studying abroad. Most of them study in the Czech Republic, but many in Germany or Austria as well.

The exodus of professionals can increase inequality in society especially in sectors such as health care or technologies, because salaries in those sectors will increase while in others will stagnate, according to Brian Fabo of the Central European Labour Studies Institute (CELSI).

“There is a visible trend in our region connected to this development,” Fabo wrote on his blog, “as salaries of doctors are growing fast because they can easily leave for a better life when compared with increase of teachers’ salaries.”

Reasons to stay abroad

In October 2015, PAS conducted a survey Talents for Slovakia in which it asked respondents why they live abroad and what would motivate them to return. In total it surveyed 132 people working abroad and 81 people studying abroad.

“It is alarming that only less than one-quarter of Slovaks studying abroad plan to live in Slovakia,” Peter Kremský, PAS executive director, wrote in the press release. “In case of those working it is 9 percent; almost 70 percent of the respondents are preparing to stay abroad indefinitely.”

When asked what would inspire students to return home, 46 percent of surveyed people listed higher wages, order and prosperity was the most important for 39 percent of people. Family finished third with 33 percent, according to PAS.

Kanka agrees that improving how the country is run could be convincing, but from following Slovak news and politics he does not see a plan to move the country forward.

“Government basically just reacts to current events and pursues populist policies to stay in power,” Kanka said. “To feel the perspective that Slovakia is going to catch up with western Europe would be an important factor for me to return.”

People want to live a decent life in a country which is well governed so their enthusiasm, energy and knowledge are rewarded for their own good and for the good of the whole society, according to Mario Fondati, partner of consulting company Amrop.

Drawing brains back

The Education Ministry wants to lure Slovak experts living abroad to the public sector in Slovakia. The cabinet gave the green light in early July 2015 to a grant scheme supporting their return. The money is destined for Slovak citizens who graduated from a prestigious foreign university and is designed to encourage them to return home.

Young experts will get €10,000 while the government wants to allocate as much as €50,000 for senior experts. The sum put aside from the state budget should be enough for some 50 people.

Bahna estimated that nearly 50 percent of recent graduates who studied abroad return to Slovakia within two years of getting their diploma (including students from top 150 universities of the Shanghai chart) according to a survey he worked on with sociologist Oľga Gyárfášová.

Moreover, the government’s stimuli would draw back just 5 percent of the working respondents, according to the PAS study. The Education Ministry responded that its duty is not to deal with migration of Slovaks and its programme is focused only on academic environment and state administration.

“Therefore we are not dealing with comebacks for lower positions or private sector conditions,” the ministry’s press department told The Slovak Spectator. “We are responsible for the education sector and in this sector the return of people with foreign know-how is desirable.”

Other approaches

What Education Ministry is doing is unsystematic, and when the funding is cut those people will leave again, according to Igor Šulík, managing partner of Amrop.

“Finances should go towards change and initiatives which can make Slovakia an attractive country that is worthy to work in,” Šulík told The Slovak Spectator. On the other hand, Slovakia can still offer possibilities for professional development, according to Michal Kovács of Leaf, the non-profit organisation focusing on development of young individuals.

For Slovaks abroad, Leaf launched a programme creating and curating job and internship opportunities, scholarships and volunteering opportunities to develop young talented Slovaks living abroad, reconnect them with Slovakia and facilitate their homecoming.

People can achieve more in a shorter time in Slovakia than they could in more developed countries and they have more possibilities to be creative, according to Kovács.

“People have the opportunity to test a new product on fully integrated European market with significantly lower risk; several banks could be an example,” Kovács told The Slovak Spectator.

Improving economy

When National Union of Employers (RÚZ) and Federation of Employers’ Associations (AZZZ) were asked what can be done to draw people back to Slovakia they both responded by improving of economy and thus working conditions and salaries.

“By gradual equalising of wage conditions in Slovakia and European countries there would be a gradual reduction in brain drain,” RÚZ’s Martin Hošták told The Slovak Spectator. “The education sector is a big challenge, particularly university-level education, because our economy will feel the migration of our best students more and more intensively.”

The state can do something with employment and salaries “but those are long-term processes, you cannot expect miracles”, Baláž added.

Learning from the experienced

Programmes battling brain drain in foreign countries such as Ireland or Israel could also be inspiring for Slovakia. The Irish periodically meet with the diaspora of clever Irish abroad who give advice to government’s institutions on how to develop the country. They also help to draw foreign investment to Ireland, according to Kovács.

Moreover many of them came back after the economic situation in Ireland improved, according to Baláž.

“The Irish have an advantage that they speak English, therefore their barriers for migration are weak and many of them went to the United States,” Baláž said. “Currently they are coming back as the situation improved.”

Israel, with its aim to become the homeland for all Jews, has more than 10 state-supported organisations connecting Jews with Israel. They organise travel for young Jews to the country of their forefathers, scientific researches with Jewish experts at world-recognised universities and organise community projects in less developed parts of Israel, according to Kovács.

Opportunity for Slovakia

The lack of educated and skilled people combined with a low birth rate in Slovakia can be an opportunity for Slovak firms to employ the long-term unemployed. Another solution for some of them is to bring foreigners to work in Slovakia: carmakers drive in employees from Romania or Bulgaria, according to Baláž.

The number of foreigners in Slovakia is increasing only mildly. There were around 14,000 working foreigners in Slovakia in 2008 and the number grew by just 4,000 people by 2015. Most are Romanians, Czechs, Hungarians and Polish. From countries which are not in the EU, Slovakia is popular with Ukrainians, Koreans and Serbians, according to the Statistics Office.

“We should deal with the problem from the other side [not luring them back],” Bahna said. “The people that leave should be replaced by skilled people from countries that would find Slovakia an attractive destination.”

(source: SITA/AP)

(source: SITA/AP)