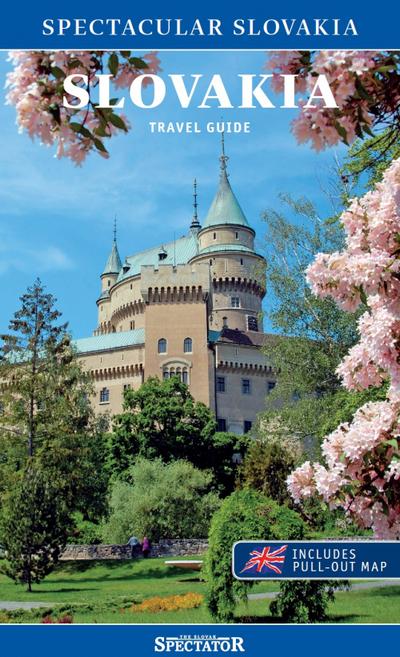

This article was prepared for an edition of the Spectacular Slovakia travel guideand was published in the travel guide Slovakia.

Monuments, synagogues and cemeteries are reminders that Slovakia once had a significant Jewish minority with a tradition enriching all spheres of life for centuries.

Jewish heritage in Slovakia

The wartime Nazi-collaborationist Slovak state deported around 71,000 Jews, with just a few hundred returning after the war – leaving behind a void impossible to fill. Still more Jewish heritage was lost when more synagogues were destroyed during the communist regime, but there are efforts underway to recover and preserve parts of this history.

New sites have been opened, albeit in places that once served for infamous purposes. The first Holocaust museum in Slovakia was opened in February 2016 in Sereď. It used to be a camp where Jews from Slovakia were sent, after their properties and belongings had been confiscated. It was not a death camp but first a work and later a concentration camp. The museum strives to exhibit items of former inmates, a cattle truck that transported Jews

A helping hand in the heart of Europe offers for you Slovakia travel guide.

A helping hand in the heart of Europe offers for you Slovakia travel guide.

to the death camp Auschwitz as well as many names of the deported. They represent only a small remainder of those who passed through the gates of the camp in Sereď. The museum also educates people about the Holocaust.

“Opening the windows for you”, is the slogan of Mazal Tov, a festival of Jewish culture held annually in early July that merges history, traditions and culture into one event.

The festival, held by the non-governmental organisation MoreMusic, offers concerts of traditional Jewish klezmer or jazz music, exhibitions, workshops, readings of literature and film screenings, as well as guided tours through Košice, Bardejov and Prešov in eastern Slovakia. These are also available in English and Hungarian languages.

“People can enter the places which are otherwise closed to the public, such as old synagogues,” said Jana Šargová, a dramaturgist and one of the organisers of the festival.

Previous years of the festival have featured Israeli musician Gitla and ethnic band Sumsum, writer Etgar Keret, jazz star Avishai Cohen and famous Slovak-Canadian photographer Yuri Dojc.

Slovak Jewish Heritage Route

The Slovak Jewish Heritage Route is a project which aspires to map the most significant Jewish sites around Slovakia, for example in Košice, Bratislava, Trnava, Lučenec or Nitra. Maroš Borský, the head of Jewish Community Museum in Bratislava, explained that the Jewish Heritage Route is a network of more than 20 significant sites, including synagogues, cemeteries or memorials coming from all regions of Slovakia.

A brochure of the route is available at the official Slovak Jewish Heritage website in both Slovak and English. The site includes an interactive map featuring the regions where the most significant Jewish monuments are located.

A considerable number of visitors, mostly the descendants of Slovak Jewish families who lived in Slovakia before World War II, come to Slovakia to visit places where their predecessors lived.

Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia

Some cemeteries have become pilgrimage sites, and these can bear more significance than synagogues which no longer serve their original purpose.

“If there’s no tabernacle with a Torah in the synagogue, it’s not a sacred place anymore,” said Pavel Frankl, the head of the Jewish community in Žilina. “Where our ancestors are buried are still sacred places. Even if the gravestone is demolished, the most important thing is that their bones are in the soil.”

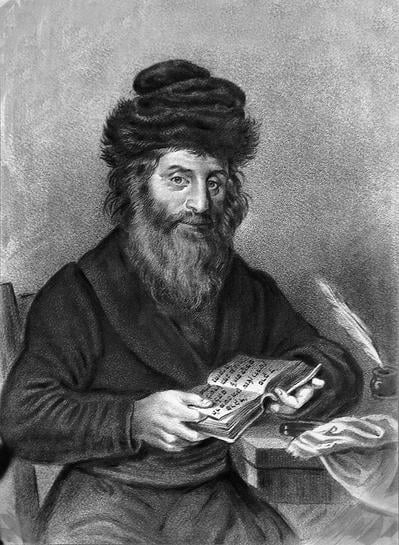

One of the most interesting cemeteries is the remnant of a cemetery in Bratislava with the grave of Chatam Sófer, dating back to 1671. At one time it contained around 6,000 graves and while the cemetery could not expand horizontally, additional layers were added to the site to hold more graves. Much of it was destroyed in 1942-43 when a tram tunnel and road were built under the castle, exiting through the cemetery.

“It is said that there were actually four layers of soil there,” said Viera Kamenická of the Museum of Jewish Culture.

One of the 23 tombs that was saved and is now preserved in a tiny underground room is the final resting place of Chatam Sófer, the orthodox scholar born Moshe Schreiber in 1762, who died in 1839. Sófer became the Chief Rabbi of Pressburg in 1806 and also headed the yeshiva (rabbinical school) in the city, one of the most prominent centres of traditional Jewish learning in Europe. The still-functioning Pressburg Yeshiva in Jerusalem was founded by his grandson.

“The only entry to saved tombs was a metallic cap in the middle of the road which looked like a drain,” Kamenická said. “I was there when I was a little girl. I remember when they opened the cap and we went downstairs to a dark place lit only by candles. There were

orthodox Jews silently praying by the Chatam Sófer’s grave. I felt like I was in a fairytale.”

Jewish Cemeteries

The tomb was preserved despite the massive societal upheavals and the scarring of the landscape. Most visitors now come in September, on the anniversary of his death, to pay their respects.

Today the cemetery looks different and has its own architecture to respect the Jewish burial rituals.

“Chatam Sófer was very gifted: as a 7-year-old boy, he knew all the five books of Moses and could also comment on them. It was an extraordinary phenomenon,” said Martin Záni, of the Jewish Community Museum. Chatam Sófer often visited the town Svätý Jur, and the synagogue there is the only still-preserved place where he spoke.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guides

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to the Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, traveller's needs as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.

Post-WWII Slovakia

Jews have always belonged to the diaspora of Bratislava, a multicultural city, and though World War II demonstrated horrible intolerance towards Jews, there have been also stories of courage on the part of Slovaks who helped them by risking their own lives during the most aggressive times of deportation. A number of Slovaks have been awarded the Righteous Among the Nations award – the highest honour given to a non-Jew by the State of Israel and Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum - for saving Jewish citizens during the Holocaust.

Of the approximately 71,000 deported Jews, only a few returned, and for many it was difficult to adjust: “Slovakia wasn’t home for them anymore because home is where you are accepted,” Kamenická said. Many emigrated to the United States, the UK, Switzerland and Israel.

The Jews who remained still maintain the traditions and feasts, but the Jewish culture’s presence in Slovakia is still most visible through the remaining synagogues.

Synagogues in Slovakia: Dynamic or decaying

There were around 100 identified synagogues in Slovakia before World War II. Most of those remaining are in poor condition today. Only seven still serve their original purpose, and more than 10 have been renovated for use for cultural events.

Synagogues

“Slovakia was an ally of Nazi Germany during the war, so the Slovak synagogues were not burned or demolished as synagogues in other states, as in the Czech Republic for example,” said Záni.

Synagogues were more likely destroyed during the communist totalitarian regime, when they were often used as warehouses.

Still, some have managed to survive. Bratislava’s only remaining synagogue is on Heydukova Street and hosts both Jewish marriages and prayers during Jewish festivals.

There is also the unique Jewish Community Museum in the synagogue. The synagogue is open from May to October and provides a permanent exhibition of Jewish heritage and history, as well as rotating temporary exhibitions.

“We don’t want to make museums for the masses,” said Borský adding that the community would like to preserve it as a still-functioning synagogue.

There are seven active Slovak synagogues, one in Bratislava, two in the south in Nové Zámky and Komárno, two in Košice, and one each in Bardejov and Prešov.

The rest of Slovakia’s synagogues are either dilapidated or used for other purposes. Some are used as museums and art galleries today, like the synagogues in Nitra and Trnava. The old synagogue in Trstená became a shopping centre and in Tvrdošín a bar. Komárno’s synagogue is a hotel with squash courts, Zlaté Moravce’s houses a climbing wall and in

Revúca the building has been converted into a centre for Jehovah’s Witnesses.

“Synagogues should be used for cultural purposes, but when there’s no opportunity to use them this way, it’s better to use them for commercial purposes than to let them become abandoned or fall into decay,” said Pavel Frankl, the head of the Jewish community in Žilina.

There are projects of synagogue renovations to make these buildings cultural centres, one of the most significant of which is a project in Žilina, organised by the non-governmental organisation Truc Sphérique.

Our Spectacular Slovakia travel guides are available in our online shop.

Jewish heritage in Slovakia

List of selected sights

Slovak Jewish Heritage Route;www.slovak-jewish-heritage.org

Bardejov: Jewis Suburb;www.suburbiumbardejov.sk

Bratislava: Chatam Sófer;www.chatamsofer.sk

Bratislava: Museum of Jewish Culture;www.snm.sk

Bratislava: Jewish Community Museum;www.synagogue.sk

Komárno: Menház;www.menhaz.sk

Prešov: Museum of Jewish Culture;www.synagoga-presov.sk

Sereď: Museum of Holocaust;www.snm.sk

Zvolen: Park of Generous Souls

Žilina: Židovská náboženská obec;www.kehilazilina.sk

Synagogues

Synagogue Bardejov (Bikur cholim);www.suburbiumbardejov.sk

Synagogue Bratislava;www.synagogue.sk

Synagogue Komárno – Menház;www.menhaz.sk

Synagogue Košice (Old)

Synagogue Košice (Zvonárska street)

Synagogue Košice (Puškinova street)

Synagogue Liptovský Mikuláš

Synagogue Malacky

Synagogue Nitra

Synagogue Nové Zámky;www.angelfire.com/hi/novezamky

Synagogue Prešov;www.synagoga-presov.sk

Synagogue Ružomberok

Synagogue Spišské Podhradie

Synagogue Stupava

Synagogue Šahy

Synagogue Šamorín - At Home Gallery;www.athomegallery.org

Synagogue Šaštín

Synagogue Šurany

Synagogue Trenčín

Synagogue Trnava - Centre of Contemporary Art;www.gjk.sk

Synagogue Trnava - Synagogue Café;www.synagogacafe.sk

Synagogue Trstená

Synagogue Vrbové

Synagogue Žilina (Neologic) - New Synagogue;www.novasynagoga.sk

Synagogue Žilina (Orthodox);www.kehilazilina.sk

Jewish cemeteries

The exact location of each cemetery is marked on the map at the beginning of this article.

Jewish Cemetery Banská Bystrica

Jewish Cemetery Banská Štiavnica

Jewish Cemetery Bardejov

Jewish Cemetery Bátovce

Jewish Cemetery Beckov

Jewish Cemetery Beluša

Jewish Cemetery Betlanovce

Jewish Cemetery Bojná

Jewish Cemetery Boleráz

Jewish Cemetery Bolešov

Jewish Cemetery Borovce

Jewish Cemetery Borský Mikuláš

Jewish Cemetery Bošáca

Jewish Cemetery Bratislava (Neologic);www.jewishbratislava.sk

Jewish Cemetery Bratislava (Orthodox);www.jewishbratislava.sk

Jewish Cemetery Brezno

Jewish Cemetery Brezová pod Bradlom

Jewish Cemetery Brodské

Jewish Cemetery Cerová

Jewish Cemetery Cífer

Jewish Cemetery Čáry

Jewish Cemetery Častá (New)

Jewish Cemetery Častá (Old)

Jewish Cemetery Častkov

Jewish Cemetery Čerhov

Jewish Cemetery Čertižné

Jewish Cemetery Červený Kameň

Jewish Cemetery Devínska Nová Ves

Jewish Cemetery Diviacka Nová Ves

Jewish Cemetery Dlhé Klčovo

Jewish Cemetery Dobrá Voda

Jewish Cemetery Dobšiná

Jewish Cemetery Dolná Mariková

Jewish Cemetery Dolný Kubín

Jewish Cemetery Dubnica nad Váhom

Jewish Cemetery Dunajská Streda

Jewish Cemetery Fiľakovo

Jewish Cemetery Gajary

Jewish Cemetery Galanta

Jewish Cemetery Gbely

Jewish Cemetery Gelnica

Jewish Cemetery Giraltovce

Jewish Cemetery Hanušovce nad Topľou

Jewish Cemetery Hliník nad Váhom

Jewish Cemetery Hlohovec

Jewish Cemetery Hniezdne

Jewish Cemetery Holice

Jewish Cemetery Holíč

Jewish Cemetery Horný Bar

Jewish Cemetery Hraničné

Jewish Cemetery Hronský Beňadik

Jewish Cemetery Humenné

Jewish Cemetery Huncovce

Jewish Cemetery Chropov

Jewish Cemetery Ilava

Jewish Cemetery Jablonica

Jewish Cemetery Jablonové

Jewish Cemetery Jelšava

Jewish Cemetery Kalná nad Hronom

Jewish Cemetery Kežmarok

Jewish Cemetery Kluknava

Jewish Cemetery Kolbasov

Jewish Cemetery Komárno

Jewish Cemetery Košice (New)

Jewish Cemetery Košice (Old)

Jewish Cemetery Kotešová

Jewish Cemetery Krajné

Jewish Cemetery Krompachy

Jewish Cemetery Kuchyňa

Jewish Cemetery Kuklov

Jewish Cemetery Kúty

Jewish Cemetery Kysucké Nové Mesto

Jewish Cemetery Lakšárska Nová Ves

Jewish Cemetery Levice

Jewish Cemetery Levoča

Jewish Cemetery Lipany

Jewish Cemetery Liptovský Hrádok

Jewish Cemetery Ľubotice

Jewish Cemetery Lučenec

Jewish Cemetery Lučenec (Old)

Jewish Cemetery Lukačovce

Jewish Cemetery Lúky

Jewish Cemetery Margecany

Jewish Cemetery Markušovce

Jewish Cemetery Martin

Jewish Cemetery Medzilaborce

Jewish Cemetery Michalovce

Jewish Cemetery Mliečno

Jewish Cemetery Moldava nad Bodvou

Jewish Cemetery Moravský Svätý Ján

Jewish Cemetery Námestovo

Jewish Cemetery Nitra

Jewish Cemetery Nitrianske Pravno

Jewish Cemetery Nováky

Jewish Cemetery Osuské

Jewish Cemetery Partizánska Ľupča

Jewish Cemetery Pastuchov

Jewish Cemetery Pavlovce nad Uhom

Jewish Cemetery Pernek

Jewish Cemetery Pezinok

Jewish Cemetery Piešťany

Jewish Cemetery Plavnica

Jewish Cemetery Podolínec

Jewish Cemetery Poprad

Jewish Cemetery Popudinské Močidľany

Jewish Cemetery Považská Bystrica

Jewish Cemetery Prešov

Jewish Cemetery Prešov (Neologic)

Jewish Cemetery Prešov (Orthodox)

Jewish Cemetery Prievidza

Jewish Cemetery Pruské

Jewish Cemetery Pružina

Jewish Cemetery Púchov

Jewish Cemetery Rajec

Jewish Cemetery Raslavice

Jewish Cemetery Reca

Jewish Cemetery Rovensko

Jewish Cemetery Runina

Jewish Cemetery Rusovce

Jewish Cemetery Ružomberok

Jewish Cemetery Rybky

Jewish Cemetery Sabinov

Jewish Cemetery Sečovce

Jewish Cemetery Senec

Jewish Cemetery Senica

Jewish Cemetery Senica (New)

Jewish Cemetery Sereď

Jewish Cemetery Skalica (New)

Jewish Cemetery Skalica (Old)

Jewish Cemetery Sládkovičovo

Jewish Cemetery Smolenice

Jewish Cemetery Smolinské

Jewish Cemetery Smolník

Jewish Cemetery Snina

Jewish Cemetery Sobotište (New)

Jewish Cemetery Sobotište (Old)

Jewish Cemetery Sološnica

Jewish Cemetery Spišská Belá

Jewish Cemetery Spišská Nová Ves

Jewish Cemetery Spišská Stará Ves

Jewish Cemetery Spišské Podhradie

Jewish Cemetery Spišské Vlachy

Jewish Cemetery Stará Bystrica

Jewish Cemetery Stará Ľubovňa

Jewish Cemetery Stropkov

Jewish Cemetery Studienka

Jewish Cemetery Stupava

Jewish Cemetery Sučany

Jewish Cemetery Šaľa

Jewish Cemetery Šamorín

Jewish Cemetery Šaštín - Stráže

Jewish Cemetery Štúrovo

Jewish Cemetery Tisinec

Jewish Cemetery Tisovec

Jewish Cemetery Topoľa

Jewish Cemetery Topoľčany

Jewish Cemetery Trenčianska Teplá

Jewish Cemetery Trenčianske Teplice (New)

Jewish Cemetery Trenčianske Teplice (Old)

Jewish Cemetery Trenčín

Jewish Cemetery Trnava

Jewish Cemetery Trstená

Jewish Cemetery Trstín

Jewish Cemetery Turá Lúka

Jewish Cemetery Turany

Jewish Cemetery Turčianske Teplice

Jewish Cemetery Turzovka

Jewish Cemetery Unín

Jewish Cemetery Varín

Jewish Cemetery Veličná

Jewish Cemetery Veľký Lipník

Jewish Cemetery Veľký Meder

Jewish Cemetery Vranov nad Topľou

Jewish Cemetery Vrbovce

Jewish Cemetery Vrbové

Jewish Cemetery Vrútky

Jewish Cemetery Vysoká nad Kysucou

Jewish Cemetery Závod

Jewish Cemetery Zbehňov

Jewish Cemetery Zborov

Jewish Cemetery Zlaté Klasy

Jewish Cemetery Zlaté Moravce

Jewish Cemetery Zvolen

Jewish Cemetery Zvolenská Slatina

Jewish Cemetery Žiar nad Hronom

Jewish Cemetery Žilina

Jewish Cemetery Žitavany

Author: Carmen Virágová

Bratislava: Chatam Sófer Memorial (source: Majer)

Bratislava: Chatam Sófer Memorial (source: Majer)

Jewish cemetery in Dunajská Streda (source: Ján Pallo)

Jewish cemetery in Dunajská Streda (source: Ján Pallo)

Prominent Rabbi Chatam Sófer (source: Courtesy of Židovské komunitné múzeum)

Prominent Rabbi Chatam Sófer (source: Courtesy of Židovské komunitné múzeum)

Žilina Neolog Synagogue (source: Courtesy of kunsthalle)

Žilina Neolog Synagogue (source: Courtesy of kunsthalle)