Fifty years have passed since the Soviet, Polish, Hungarian, Eastern German and Bulgarian tanks invaded then Czechoslovakia and trampled on the dreams of ordinary people. The invasion on August 21, 1968, was followed by normalisation, a process during which the country fell back into its old totalitarian rut. Thousands of people fled for a better life in the West and others emigrated into themselves, trying to live their ordinary lives hidden from the long arm of the repressive regime.

“The invasion was a huge shock for ordinary people,” said historian Ľubomír Morbacher of the civic association Living Memory, which educates young people about totalitarian regimes so as to spur their critical thinking, adding that unarmed people stood against the tanks and explained to the soldiers that there is no counterrevolution. “This huge uprising, the solidarity between people and their non-violent resistance actually left its mark on one entire generation. Then the consequences of the normalisation process literally devastated society, along with thousands of people emigrating, because they realised that the socialist regime cannot be reformed.”

What preceded the invasion?

In early 1968, the communist regime loosened its tight grip on the country, belonging to the sphere of the Soviet Union’s interest following WWII. Reformist Alexander Dubček was elected the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ).

Living Memory

Founders of the civic association Living Memory Miroslav Lehký, Ľubomír Morbacher and Martin Slávik believe that freedom and democracy are not a matter of course and that after the transformation from a totalitarian regime to a democratic one, it is not enough just to build formal institutions of a democratic state respecting the rule of law, but that a change in the thinking of people is necessary. In their opinion, coming to terms with totalitarianism in Slovakia has been delayed, slow and inconsistent. To help this process while fighting against growing hatred and extremism, they visit schools and talk with students about the advances and values of freedom and democracy, the past, fear and lack of freedom.

“All society was braver after Nikita Krushchev uncovered Stalin’s cult of personality in the late 1950s,” explained Morbacher, adding that Czechoslovakia during the second half of the 1960s was ripe for a change. “People began to believe that a socialist reform or their own path to socialism with a human face was possible.”

But the Soviet Union was watching Czechoslovakia closely and similar to eastern Germany back in 1953 and Hungary in 1956, it intervened in Czechoslovakia. Its troops, accompanied by the troops of other Warsaw Pact’s countries, with the exception of Romania, invaded the country on August 21, 1968, and dampened all the reforms.

Normalisation

What followed was the normalisation process, i.e. returning the country to the regularity of the totalitarian regime. Gustáv Husák, originally a close ally of Alexander Dubček during the Prague Spring, changed sides and was elected the KSČ’s First Secretary. Along with Vasil Biľak, he became the symbol of normalisation, which meant a halt to all democratisation processes and a return to a repressive communist regime.

“Again, the media was censored and people had to request permission to travel to the West,” said Morbacher. “Extensive purges followed in mass media, in all segments of the society, as well as in the KSČ.”

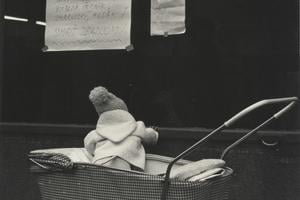

A tank in Bratislava during the August invasion in 1968. (source: TASR )

A tank in Bratislava during the August invasion in 1968. (source: TASR )