This story was produced in partnership withReporting Democracy, a cross-border journalism platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

The adverse consequences for children of shutting schools during the Covid-19 pandemic are well-documented, wide-ranging and long-lasting. With Slovakia having administered one of the longest school closures globally, growing divisions have opened up within government and between experts about how best to handle children’s education as another deadly wave of the pandemic engulfs the country.

Unlike last year, when schools shut in mid-October 2020 for most pupils and ended up staying closed for more than half a year, the Slovak government opted to leave schools open this time around as it tried to strike a balance that would both mitigate the pandemic and avoid the kind of harsh lockdown imposed across the country last winter.

However, it took a veto by the education minister and his Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) party in a cabinet session of the four-party coalition on November 24 to halt a push to close the schools.

Education Minister Branislav Gröhling argued for leaving schools out of countering the pandemic this time around, saying the younger generations should no longer be made to pay for the decisions of adults. “Closed schools will not solve the pandemic for us; what solves the pandemic is that we go and get vaccinated to get out of this whole situation,” Gröhling told a November 26 press conference. He also argued that closures would go against World Health Organization guidelines.

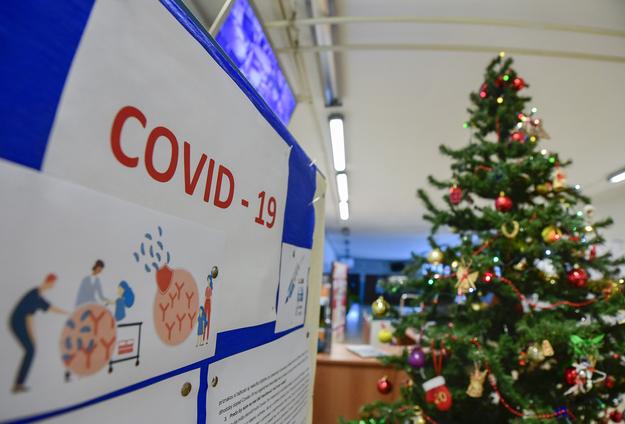

Ultimately, the government decided on December 7 that schools around the country should switch to online learning from the fifth grade upwards one week before the Christmas holidays, on December 13, as part of what experts have described as a half-hearted lockdown imposed on the country.

At the start of the lockdown on November 25, all primary and secondary schools, special schools, and kindergartens remained open, on paper at least, with a reintroduced mask mandate for pupils and an order to mix classrooms as little as possible. The Education Ministry halted all after-school activities, language schools and art schools. “We aim to keep as many pupils as possible in schools until the holidays,” Minister Gröhling said on November 26.

(source: TASR)

(source: TASR)

(source: TASR)

(source: TASR)