A glossary of words is also published online.

Life would be so much easier for people with hearing loss if we all lived in a silent Slovakia.

“I was being constantly mocked. Schoolmates were reluctant to help me when I needed to copy their notes,” Tomáš Dunko, a university student who lost his hearing at the age of 3, recalled one of his childhood memories, adding that his life did not become much different at Slovak universities, “There are people who take me as an equal and others who do not for their reluctance.”

Born to hearing parents, Dunko is fluent in spoken language. He is a lip reader, a hearing aid user, and he also uses Slovak Sign Language (SPJ), which he regards as his second mother tongue. However, having a command of all these skills is not as common in the community. Dunko himself, despite his effort, faces communication barriers on a daily basis.

Though the pandemic did make people with hearing loss more noticeable thanks to SPJ interpreters appearing on television, it did not help root out people’s and the state’s ignorance of this community and its needs. “It is much worse these days because of face masks,” the university student said, explaining that hearing people, whether on television or in person, often do not take their masks off when addressing a deaf or hard-of-hearing person. As a consequence, a larger part of the community, which does not sign, is left more isolated and uninformed.

Out of the estimated 250,000 deaf or hard-of-hearing people in Slovakia, less than 5,000 are said to sign. The first official figure on SPJ users will be released in 2022.

Regardless, after the years of disregard and ongoing discrimination, the 2020 codification of Slovak Sign Language is understood as a step forward. “For the Deaf community, it was definitely not just a symbolic moment,” the Slovak Association of the Deaf (SZN) Chair Jaroslav Cehlárik said. A case in point, following this major change, deaf people could select SPJ as their mother tongue for the first time in the 2021 Slovakia Census.

Codified, but where are the rules?

Rarely had sign language been considered an adequate form of communication in society before its codification, even though it was recognised by law in 1995 and added to a list of the country’s intangible cultural heritage – under the name of Slovak Sign Language - in 2018.

“Codification will strengthen the position of Slovak Sign Language as an independent language,” the Culture Ministry is convinced.

Slovak Sign Language, which has different varieties and is also different from Slovak and a manually coded language following the written form of the Slovak language, has a chance to become standardised after almost two centuries. Sign language appeared on the territory of what is today Slovakia in the first half of the 19th century, when the codification of the Slovak language took place.

People with hearing loss can live a full life, but society must be able to accept it.“

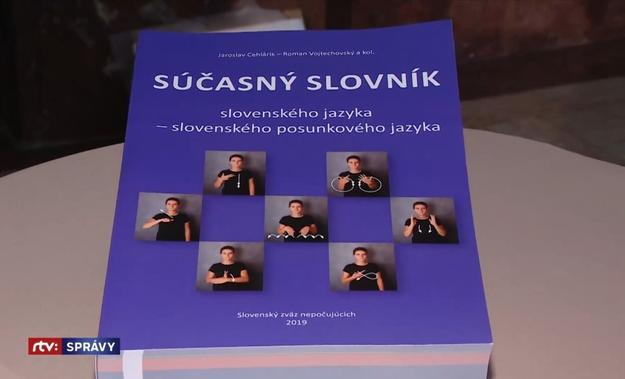

Because of the unfortunate past, Slovakia does not yet have many experts that research Slovak Sign Language. Still, several experts and people from the Deaf community joined forces and published the first book of language standards in 2019 with the €30,600 they received from the Culture Ministry a year before. “Thanks to this, codification could take place,” said Cehlárik. He co-authored this book, which is called The Contemporary Slovak-Slovak Sign Language Dictionary.

Yet, as The Slovak Spectator understands, most people in the community have not seen or heard of the book. It is not available in libraries, nor in bookstores, and the dictionary, allegedly, remains just a working copy.

One of the people who helped Cehlárik with his book project is Roman Vojtechovský, a well-established SPJ expert who himself is deaf. He is also one of the TV News presenters that communicates in Slovak Sign Language, which has been broadcast by the public broadcaster RTVS since 2013. Five years ago, in 2016, Vojtechovský and his organisation SNEPEDA launched the online bilingual dictionary Posunky.sk. The dictionary - also a working draft - contains about 9,000 signs as of today.

“It will take a long time to complete it, but I believe the dictionary is useful,” he said.

The Culture Ministry said it would be more convenient if SPJ standards were published online as language is a living organism. A subsidy can be provided, the ministry added.

First trained sign language interpreters

Nonetheless, no dictionary is likely to resolve a more urgent problem in the community with hearing loss: the shortage of SPJ interpreters. The Office of the Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities, moreover, said interpreting services did not work equally well in regions.

“This significantly worsens the quality of life of deaf people,” Cehlárik said. Some cannot find their dream job, while others cannot speak about their mental health issues with an expert. “Deaf children who, when born into hearing families, do not have the opportunity to learn SPJ at a time when they should acquire it,” Cehlárik said, claiming that conditions in schools for these children were not good in this regard.

To become a SPJ interpreter and provide the interpreting service within the institutional framework in Slovakia, a person has to be certified. But a body issuing certificates in the past no longer does it, the highly experienced certified SPJ hearing interpreter and lecturer Robert Šarina said. As a result, today’s small network of interpreters, mostly the children of deaf parents, has not expanded over the past few years.

To raise the first generation of professional interpreters, Trnava University opened the unique Slovak Language in Communication with Deaf People degree programme, now studied by 51 students, in September 2020.

Meanwhile, if they do not have access to an interpreter in the flesh, deaf and hard-of-hearing people preferring sign language can use online interpreting services provided by the Pontis Foundation and Šarina’s Centre for Barrier-Free Communication. “Several institutions are trying to remove communication barriers and use online interpreters or ask to have texts translated into Slovak Sign Language,” Vojtechovský said. Many hearing people have tried learning or continue to learn sign language as well.

Paradoxically, the part of the community with hearing loss that uses sign language, which has been a core part of Deaf culture, might lose it in the future.

Šarina, who grew up surrounded by deaf people, noted: “The community is dying out because advanced technology can help a deaf child become a hard-of-hearing child that can speak and does not need to sign.”

Lip-readers struggle too

The group of people with hearing loss that does not sign is larger, in fact, but equally forgotten about.

Relying on people’s lips - if they do not have a hearing aid - is how this group communicates with their hearing counterparts. The introduction of masks has put the group at a greater risk than the group using sign language during the pandemic, the Office of the Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities said, because they do not have access to information at all.

“Many people with hearing loss have great difficulty reading and understanding the text,” the office added, “Therefore, it is not possible to accept the argument that they can read information about the pandemic online, in newspapers or in leaflets.”

Television channels have long been failing to ensure all their programmes are subtitled for deaf and hard-of-hearing people. The public broadcaster RTVS offers the highest number of subtitled television programmes, but only two programmes broadcast in SPJ. The Culture Ministry has proposed RTVS subtitles for all its programmes.

Jana Filipová, the chair of the Association of the Deaf of Slovakia (ANEPS), said the communication barrier will always be there because hearing loss is invisible, noting that society did not learn to distinguish between degrees of hearing loss. “People with hearing loss try to communicate with the public,” Filipová said, “and hearing people do not have to be afraid to learn sign language and to communicate with such a person either.”

Hard-of-hearing researcher at Comenius University Miroslava Tomášková believes that myths about the community should also be debunked among the public.

Dunko is convinced the discrimination of his community will end in the future. He said: “People with hearing loss can live a full life, but society must be able to accept it.”

The Spectator College is a programme designed to support the study and teaching of English in Slovakia, as well as to inspire interest in important public issues among young people.

Declaration on the codification of Slovak Sign Language was signed in Bratislava on September 23, 2020. (source: Office of the Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities)

Declaration on the codification of Slovak Sign Language was signed in Bratislava on September 23, 2020. (source: Office of the Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities)

Jaroslav Cehlárik chairs the Slovak Association of the Deaf. (source: TASR)

Jaroslav Cehlárik chairs the Slovak Association of the Deaf. (source: TASR)

The Contemporary Slovak-Slovak Sign Language Dictionary. (source: RTVS)

The Contemporary Slovak-Slovak Sign Language Dictionary. (source: RTVS)

The family festival of Slovak Sign Language took place on a football pitch in Opoj, Trnava Region, on August 21, 2021. (source: TASR)

The family festival of Slovak Sign Language took place on a football pitch in Opoj, Trnava Region, on August 21, 2021. (source: TASR)