English-language fiction is the main gate into the world of literature. English translations of books by contemporary Slovak authors are still scarce, but in recent years their promotion has somewhat shifted. It turns out that the demanding efforts to cultivate contacts with English publishers might not be just vain attempts.

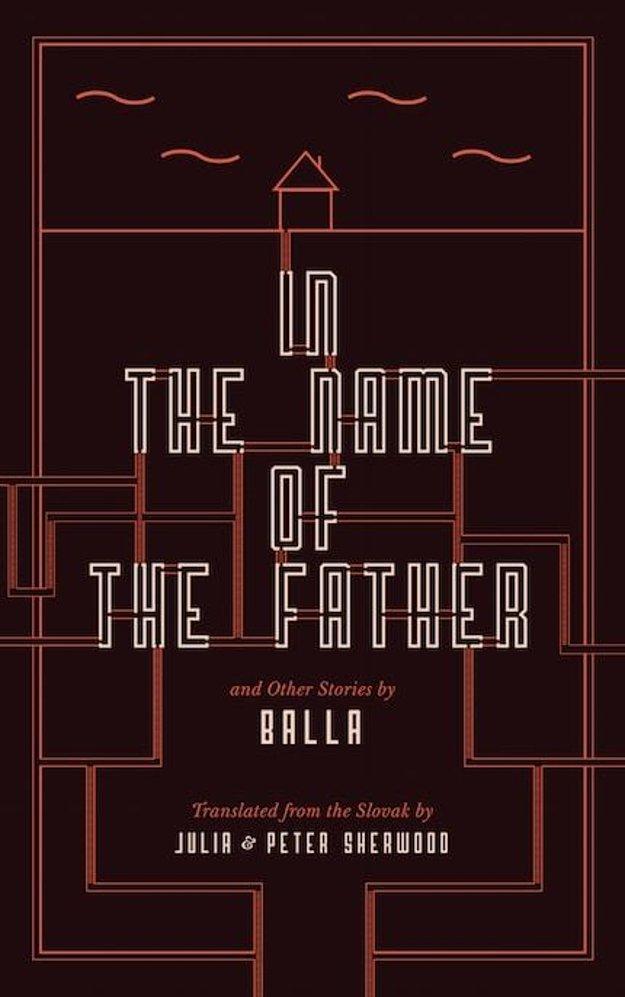

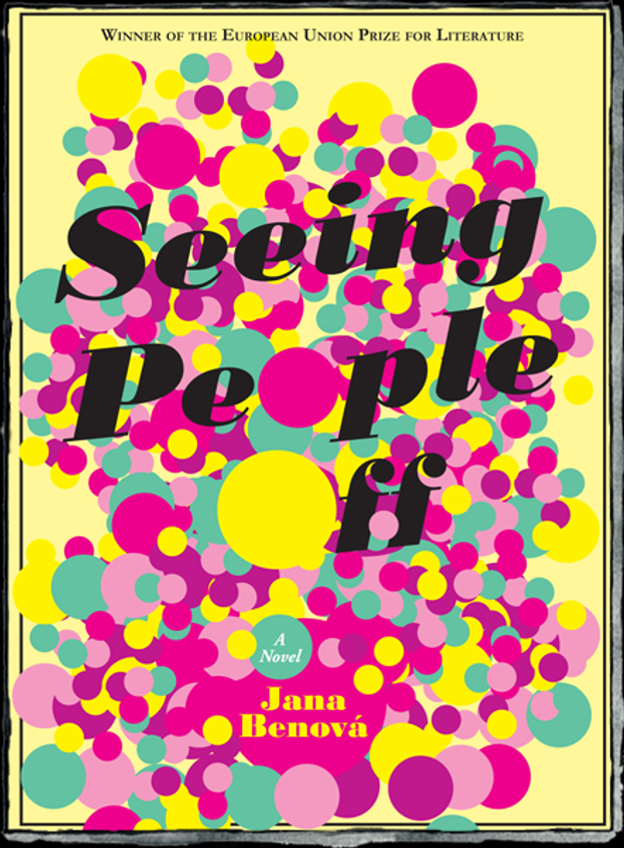

This week, three titles of contemporary Slovak fiction are set to be launched on the Anglophone book market: Seeing People Off by Jana Beňová; In the Name of the Father by Balla; and an anthology of contemporary Slovak fiction. It is a big deal, as they will be introduced in one of London’s biggest bookstores.

Nobody can guarantee readers will notice, but critics confirm that it makes sense for Slovak writers to seek out a way to the world.

Why language deteriorates

“I have lived in London for years now and I follow the book market, but I still haven’t found the miracle formula that would open the possibilities and start intensive interest in Slovak literature,” known translator of Slovak origin Júlia Sherwood told the Sme daily.

Sherwood wanted to study translation and interpreting in the pre-1989 Czechoslovakia, but failed repeatedly to get admitted, despite her excellent study results. It was clear why she was subjected to such bullying— she is the daughter of journalist and publicist Agneša Kalinova and writer Ladislav Kalina, whom the Communist authorities labelled the subverters of the socialist republic.

Ten years later, following years of persecution, the family emigrated in 1968 along with the big wave of emigrants who left Czechoslovakia after the invasion of Russian troops.

“I have met many of our people abroad whose mother tongue went incredibly bad over the years,” Sherwood says. “That’s when I made the resolution that I cannot let the same thing happen to me.”

Only years later she returned to translating, influenced by her husband, a Hungaristfrom London, who is her adviser on the potential versions of translations and in the selection of books to translate. He is also the one to give the final brushing to the texts.

In 2014, for instance, they translated the book by Jana Juráňová, Ilona: My Life with the Bard. It tells the story of Ilona Országhová, the wife of Slovakia’s classic Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav.

“Though he is our biggest poet, we have agreed not to use the name Hviezdoslav in the title of the English translation [as it is in the Slovak original],” Sherwood said and explained that it would mean nothing to the readers abroad.

Success is uncommon

The main problem remains the same as it has been in the past—Slovak literature is a big unknown in the UK and does not have the supporting pillars as Czech literature does in the tradition of Hašek, Hrabal, or Kundera.

Rivers of Babylon, by Peter Pišťanek and Samko Tále, by Daniela Kapitáňová found success among the English critics, but it is hard to say how that translates into the numbers of sold copies, Sherwood says about the English translations of Slovak books in the past.

The book The Equestrienne, by Uršula Kovalyk was also welcomed in London, but the sales numbers are yet to be seen.

The novel by Peter Krištúfek, House of the Deaf Man, performed quite well, since it is a voluminous historical novel that now belongs to the favourite types of books among readers around the world.

“It’s not that it would sell thousands of copies, but the publisher is satisfied,” Sherwood says and adds that the sales of the book are comparable with the sales of books by English writers who are starting to make their name, and that can be seen as a success. This is also thanks to the personal presentation by the author in English at the international book festival in Edinburgh.

Reason is a secret hit

Translator Abram Muller has similar experiences with Slovak literature in the world. He has translated the books of Rudo Sloboda, Balla, Dušan Mitana, and short stories by several other Slovak writers into Dutch.

He says the books received quite a lot of attention in the Dutch media and they had good reviews, even in the major Belgian daily De Standard.

“It is a joyful, amazing feeling,” Muller says. “I was surprised, because it happened completely without connections. The editors found the books on their own.”

The reasons for the independent interest is the innovative approach of editors and the young publisher with a vision who publishes the books.

Despite good reviews, however, he is aware that they do not have the potential to become bestsellers. Yet he discovered that Reason, by Rudo Sloboda was a secret hit. The translation was published two years ago and it is still on display in bookstores.

The experiences of both translators confirm that big novels stand a chance. But don’t be hasty—it’s better to be a good author than a good graphomaniac.

©Sme

(source: PARTHIAN BOOKS)

(source: PARTHIAN BOOKS)

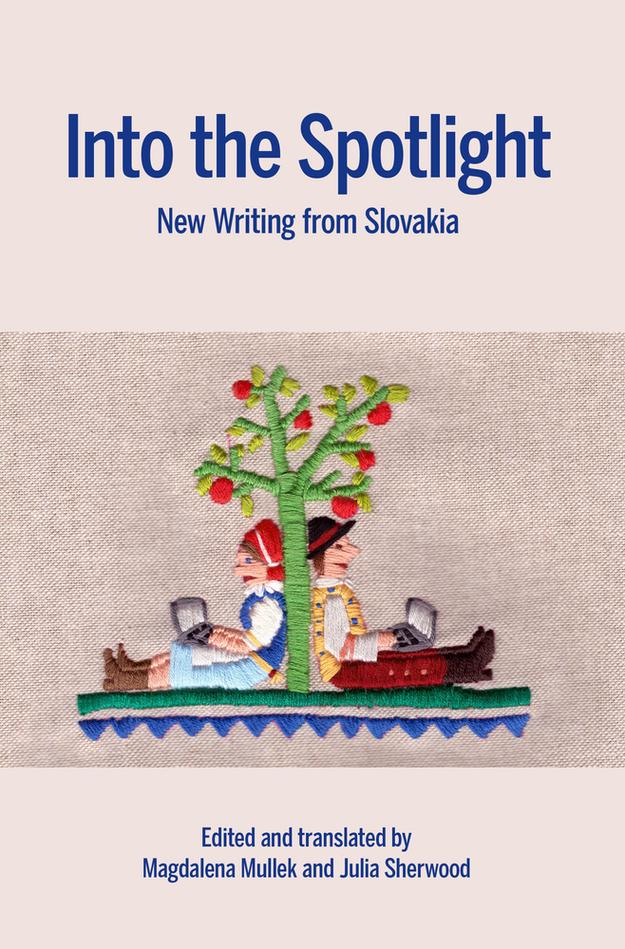

On Wednesday, Slovak literature will be presented in one of the biggest bookstores in London. Among the new books translated into English is also the anthology of current Slovak prose selected and translated by Magdalena Mullek and Júlia Sherwood. (source: PARTHIAN BOOKS)

On Wednesday, Slovak literature will be presented in one of the biggest bookstores in London. Among the new books translated into English is also the anthology of current Slovak prose selected and translated by Magdalena Mullek and Júlia Sherwood. (source: PARTHIAN BOOKS)

(source: Jantar Publishing)

(source: Jantar Publishing)

(source: TWODOLLARRADIO)

(source: TWODOLLARRADIO)

(source: ABRAMMULLER.COM)

(source: ABRAMMULLER.COM)