Today we can hardly imagine what life in mediaeval Bratislava, then Pressburg, was like. At that time between 5,000 to 10,000 citizens lived here with no sewer system. Each household had a yard, in which they raised livestock and poultry. As a consequence, a perpetual stench engulfed the area.

Yet people lived similarly as they do today; committing crimes just as contemporaries do: stealing, fornicating or murdering. The “only” difference is in which deeds were considered criminal offences and which interrogation methods and punishments were used. This is because torture used to be an inseparable part of legal proceedings, and of course, of punishment.

“Mediaeval man did not differ at all from contemporary man in terms of mentality,” states historian Vladimír Segeš from the Institute of Military History and author of a book about crimes from mediaeval Bratislava, Prešporský Pitival, during a lecture about criminality in Pressburg organised by the non-profit organisation Bratislavské Rožky and dedicated to the history of Bratislava.

Criminality in the Middle Ages

The topic of criminality in the Middle Ages only recently came into the focus of attention of Slovak historians. Also Segeš came upon this theme only by chance when he was researching the history of warfare in mediaeval Bratislava.

When studying historical materials he found not only a great deal of information about warfare but also about the common life of people at the time. Particularly the so-called Kammerbücher, a kind of accounting books kept by towns, proved to be a rich source of information for him.

In the Middle Ages, most people were illiterate. They did not travel and were bound to the place where they were born. Only certain groups of citizens used to travel, for example, nobles, merchants, soldiers and of course apprentices.

During those days the system of law was very multifarious when several partial law systems co-existed: for the nobility, the municipal law or the canon law. Also guilds had their own system of law.

“During the Middle Ages no complex and unified criminal law was adopted, i.e. a criminal code for the entire [historical] Hungary,” said Segeš.

Criminal offences

Criminal offences were divided into public and private. The first group included treason, but also unfulfilled promises, offences against life, decency or property. The second group included, for example, libel. Many of these historical offences are crimes today.

“Manslaughter or assassination is still manslaughter or assassination today,” said Segeš.

But in modern times criminal offences are assessed and punished differently. For example, in the Middle Ages punishment by imprisonment did not exist.

Three times of torture

Trials were held on the first floor of what is now the Old Market Hall at the Main Square. Characteristic of trials was a kind of theatrical ritualism and formality.

Confession played a key role, while the court did not scrutinise whether it is true or not, i.e. whether the person really committed the crime or whether he made the confession himself, or whether he was forced to make it by torture.

Each of the accused was investigated three times, except those caught red-handed when committing a crime. In such a case there was no need for investigation and the culprit was convicted and punished immediately.

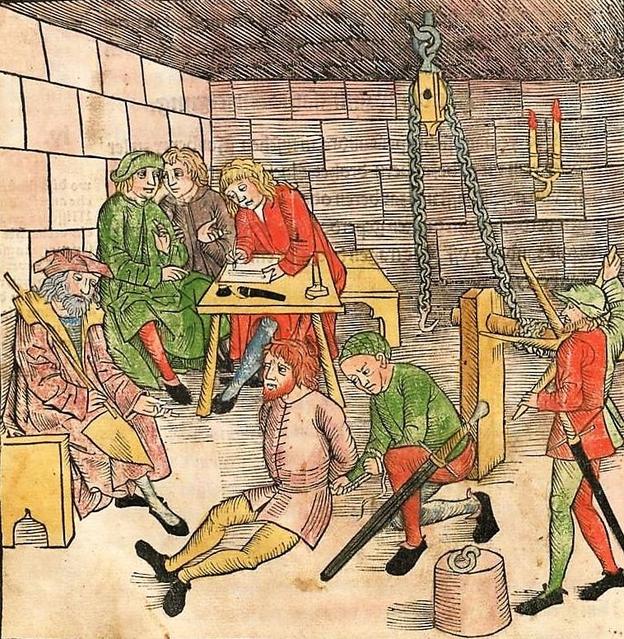

The whole process of interrogations and torture usually lasted about two weeks. Preserved historical documents mention that in Pressburg, clamps and candles for burning were the most often used torture instruments.

But also sticking the accused with a needle, nail or emblazed iron were popular.

“At first, the hangman only showed the torture instruments to the accused,” said Segeš. “During the second seating, when the accused did not make the confession, he was tortured. In case he did not confess, he was interrogated and tortured also for a third time. In case he did not confess the third time, and there were some such cases, he was simply released as innocent.”

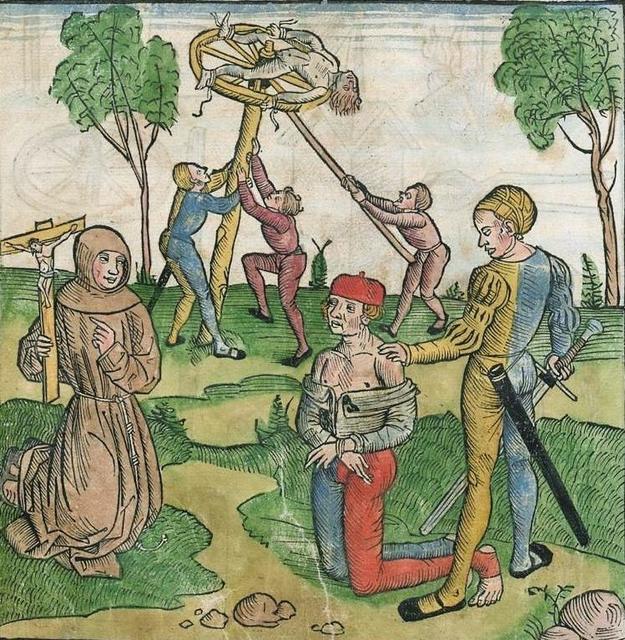

Death sentence

The most serious punishment was the death sentence; the method of execution based on the seriousness of the committed offence. For example, for thievery, the culprit was hanged by the neck. In Bratislava, the gallows used to stand in front of Michalská Brána gate, on the border of Župné and Hurbanovo squares.

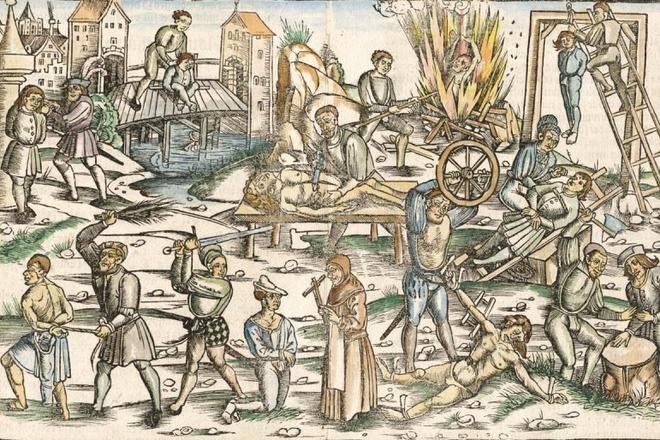

But other techniques included hanging by the ribs, burning at the stake, drowning or execution by the breaking wheel. The latter, which was an exceptionally cruel way of execution, was used for executing thieving killers.

The most frequently mentioned non-capital punishment in Kammerbücher was pillorying. The pillory stood on the Main Square close to the town hall.

The Pressburg law book also allowed for mutilation punishments.

“In the Middle Ages people perceived justice and satisfaction differently,” said Segeš. “This means that everybody took these punishments as something normal and natural. Man in the Middle Ages believed in fulfilment of justice much more than they do today.”

A depiction of punishments in the mediaeval justice system. (source: Laienspiegel)

A depiction of punishments in the mediaeval justice system. (source: Laienspiegel)

Mediaeval justice (source: Bambergische Peinliche Halsgerichtsordnung - Constitutio Criminalis Bambergensis from 1507)

Mediaeval justice (source: Bambergische Peinliche Halsgerichtsordnung - Constitutio Criminalis Bambergensis from 1507)

A depiction of punishments in the mediaeval justice system. (source: Bambergische Peinliche Halsgerichtsordnung - Constitutio Criminalis Bambergensis from 1507)

A depiction of punishments in the mediaeval justice system. (source: Bambergische Peinliche Halsgerichtsordnung - Constitutio Criminalis Bambergensis from 1507)