ETHNOGRAPHER Jana Belišová, 37, used to spend her summer holidays at her grandma's house in Žehra, a tiny village near the eastern Slovak town of Prešov. Every evening, she listened to the singing that drifted in from a Roma settlement on a nearby hill just behind the village. During the day she played with the Roma kids, but had to keep this fact secret from her grandma for fear of angering her.

"Being friends with the Roma was frowned upon, the same as being friends with a gang of hooligans," she says when recalling her childhood.

Her grandmother is no longer living, yet Belišová continues to visit the Roma settlements. She works for the civic organization Žudro, and today she is openly friends with many Roma.

She uses these contacts to seek out authentic Roma music like the songs her little Roma friends used to sing. She has been professionally devoted to preserving the songs, which are slowly disappearing, for 14 years now and, with the help of her colleagues, she has produced a compact disc, a songbook, and a diary that relates the team's experiences working on this project.

"It is great that somebody decided to preserve these songs that are disappearing, because today's youth focuses mainly on modern trends," says Daniela Šilanová from the civic association Jekhetane.

Entitled Phurikane giľa or Ancient Roma Songs, the CD presents 28 songs performed by various artists. It is a selection from more than 130 songs Belišová's team recorded during last year's travels around various Roma settlements in eastern Slovakia.

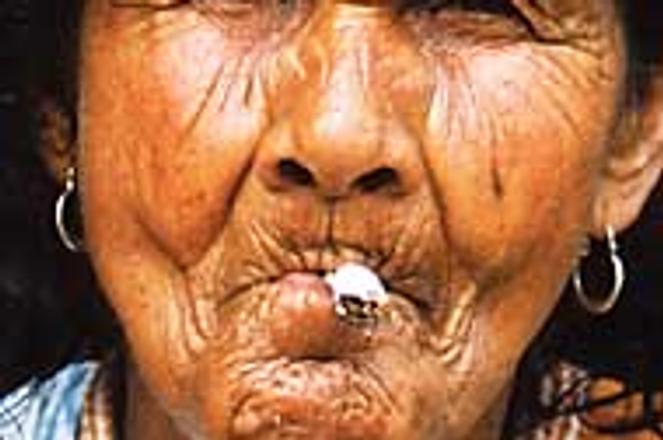

ROMA women are the guardians of their ancient culture. Researchers found some who were willing to share a vital part of it, hidden in their songs.Photos by Daniela Rusnoková and Jana Belišová

"We focused primarily on the slow mournful songs called halgató, [which are improvised stories]. And because we had to dig them up from oblivion, our research project seemed a bit like a rescue mission," Belišová says.

The CD also contains livelier dance songs called čardaša, but only the halgató are in the songbook.

The researchers had to search for older people to help them, because young people, who prefer the mix of Roma and popular music known as "rompop", do not know much about the old songs. However, their parents or grandparents often refused to sing when asked, saying they were ill, tired, or fed up with their lives.

"I believe that in the mournful songs Roma hide their sad history...They might not appreciate it yet, but in the future [the project] will mean a lot, not only to them but also to others," Belišová said.

Most of the songs on the CD are solos, but some are sung by two singers or a group, and from time to time the performers are accompanied by an instrument, usually the guitar or accordian. Clapping or finger snapping supplements the percussion.

All the recordings were made using a single microphone in the singers' houses. That is why in the background one can hear additional voices and various noises, such as laughter, a child crying, and the squeaking of a door. The recordings are surprisingly clear despite that.

The CD, songbook, and diary are sold as a package in selected bookstores around the country, e.g. in Artfórum on Kozia 20 in Bratislava for Sk670. Tel: 02/5441-1898.Photo: Spectator archive

Apart from the fact that the songs are slowly disappearing, Belišová wanted to collect the ancient Roma songs because she felt the musical qualities of the Roma, who have always been pushed to the margins of society, were flouted or falsely presented.

"The most-used argument against their natural talent was that they don't actually create but only reproduce. This opinion of Roma musicians has spread, maybe because few of its defenders have had an opportunity to get to know the authentic Roma folklore," she explains, adding that many considered the music Roma played at weddings and other social events to be genuine Roma music. Those musicians, however, adjusted to the demands of mainstream society and played what the non-Roma liked.

"We thus have to seek out authentic Roma music in its natural environment: Roma settlements, where the original songs live in their intimacy, without being altered for a certain audience," she says.

The accompanying book, illustrated with photographs, is a kind of diary that narrates the experiences and impressions of Belišová's several teams, consisting of two students, a writer, a Roma activist, a photographer, an artist, and her husband.

"Our experiences on our journeys were so strong and important to us that we decided to publish them," Belišová says.

Like the story of Etela, the first person they met after three days of searching who was willing to sing. The big, slow, serious 48-year-old woman with a deep voice and a sad look has never married. When she was little, boys threw her into a fire. She has burns all over her body.

When it came to the recording, Etela nearly changed her mind about cooperating with the researchers.

"She was not in the mood to sing," Belišová relates in the book. "But because she had promised to sing, she wanted to keep her word. She took us to the small house where she lived with her 77-year-old mother.

"Finally we got to hear the songs we were looking for."

- with Saša Petrášová