Vladimír Godár (1956) studied composing at the Conservatory of Bratislava and was an editor in the music publishing house OPUS. As a composer of film music, he got two Czech Lion awards and made his reputation mainly with music to movies by director Martin Šulík. With Czech singer Iva Bittová, he recorded the album Mater, and on the occasion of his 60th birthday, the Slovak philharmonic premiered his oratory Orbis sensualium pictus in March 2016.

Artists tend to be busy from early morning until late evening without getting to work on what they really believe in, said composer Godár, explaining for the Sme daily why it’s an exception for him to accept orders to compose music.

SME: Once, you said that the role of art in Slovakia is to open people’s eyes after decades of lacking freedom. Do you think that contemporary artists succeed in doing so?

Vladimír Godár (VG): We have not created a society approving and favouring art. While art used to be limited by ideological repressions, it was able to keep or find the raison d’être. Today, artists mostly strive to keep their personal integrity. Moreover, art has always been connected with younger generations – a young person is more eager to express their stance, despite existential issues. However, if they want to create something of value, they have to find their own ideal. For a young filmmaker, this could be Fellini – the greatest artist of the 20th century, according to me. But even he was ultimately eliminated by capitalism.

SME: Why is the stance of Slovak society towards art so half-hearted?

VG: I think the mistake is not on the side of society. This problem is currently not a merely Slovak one, it is global. Politicians or managers ceased to listen to artists. In the 19th century, they still had respect towards thinking and ideas; but in the 20th one, they gradually stopped being interested in philosophers, later in theologians, and today, even scientists are of no interest to them. This can be shown by Albert Einstein who experienced a huge personality cult although only few understood his discoveries and findings. The work of today’s scientist is not connected with social acknowledgement, even if the scientist discovered a remedy against cancer. Politicians are interested in scientists only if the latter can expand their power – and the same can be said about artists. But art has not ceased to desire for this wider consent. Cicero wrote, in his work Brutus, that the real goal of good rhetoric is general consent, in which the opinion of scholars merges with the opinion of the crowds. Artists have taken over this goal of rhetorical speakers. For my generation, such universal personalities were represented by musicians from The Beatles, for a slightly younger generation it was, for example, Michael Jackson.

SME: Let us go back to your idea of lack of freedom. How did you fight it before the Velvet Revolution [of 1989 that toppled communism]?

VG: I cannot evaluate it quite well. Maybe the communist regime used me partially, but I do not think I failed to keep my integrity.

I had one mantra then, meant to protect me. It is from Pushkin’s essay Voltaire: “Only independence and self-esteem can edify us to a level above the trivialities of life and storms of Fate.”

SME: Did you experience moments when you had to remind yourself of this?

VG: Yes, possibly when I felt limited in my movements and whereabouts. When I was on a scholarship stay in Vienna, during which I was able to discover Austrian libraries and their cultural life, I realised fully the limits of our country.

On being a composer, making a living and refusing attractive offers

SME: Have you ever doubted the career of being a composer?

VG: Being a composer has never been an existential career for me, I made my living as an editor, later as a scientist-historian, and still later as a teacher. I have never depended on music existentially, I stayed free towards it.

SME: Could you not make your living from it?

VG: I have never even tried. If I compare my career with my schoolmate and friend Peter Breiner, I have the impression that he would not have accomplished many of his works, if had he the free choice. Peter is extremely hardworking but if he could, he would probably put more energy in his own artistic visions. This, too, is connected with rewarding the art. [US film director of Czech origin Miloš] Forman said that if he makes one movie that captures America, then he can work for four to five years on something he believes in. The amount of royalties in Slovakia result in artists who are busy from early morning until late evening doing things they are not really interested in; and thus, they create chaos in their own heads.

SME: Have you had a great foreign offer that you refused?

VG: I had one which I did not make. British cellist Julian Lloyd Webber ordered a concert with me which I did not write. Hard to tell why. I am probably not able to react well to orders. I do not have it in my basic equipment.

SME: Do you have a problem when someone dictates to you what he wants to hear in your work?

VG: No, but many of my problems with film directors appeared when we failed to find a common language and we did not understand one another. I composed film music when I was able to accept the due film. Today, it happens ever more frequently, that a conflict appears during the work that may have a generational background. In fact, I only really have an understanding with Martin Šulík now who also has ever bigger problem getting to work on something he believes in…

SME: Does it happen often here, that a composer of classical music gets money for a composition connected with just one specific event – and composes it, not expecting to hear about it anymore?

VG: A composer should make music mostly for himself, to understand himself as the listener whom he gets to know familiarly. What you said means stating a situation when some mediating institution gets between the artist and the listener. Grant systems represent the death of independence and self-esteem. I perceive their boosting and cultivation as the true function of art. If the artwork does not spread independence and self-esteem in society, it does not make sense anymore, even if multiple grants contributed to its creation.

SME: How could this financing function?

VG: Let us ask Leonardo da Vinci what grants he filled in during the nights.

SME: But he also worked often on order.

VG: It is often said art or music is killed by lack of finances. However, a more reliable death for art or music is their connection with big money. Once, I heard an interview with a person who discovered for the world the music of Dylan and Springsteen. They asked him how he managed to do it. His answer was: I need to find a person who has negative social experience and who is able to define that experience. I will make him a millionaire, and he himself has then to sort out the problem how not to go crazy because of this new existential dilemma of his.

SME: Do you think a musician cannot bear fame and money?

VG: I read a book by Cynthia Lennon – it is about John, her ex-husband. At the time of his culminating fame, she stopped recognising him; he started to use hallucinogens. Their son Julian, then aged nine, asked her: Dad still says people should love each other, so why does he not love me?”

SME: Can a musician lose humanness?

VG: Probably, he can. When his ego grows, his ruthlessness towards reality also grows. The traps humans set for themselves can be tricky.

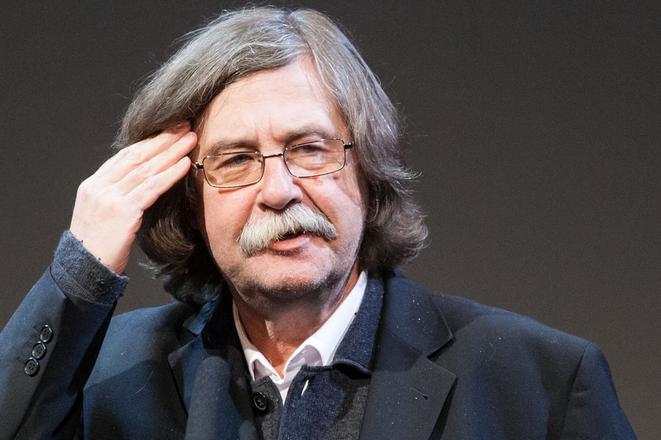

Slovak composer Vladimír Godár (source: SITA)

Slovak composer Vladimír Godár (source: SITA)

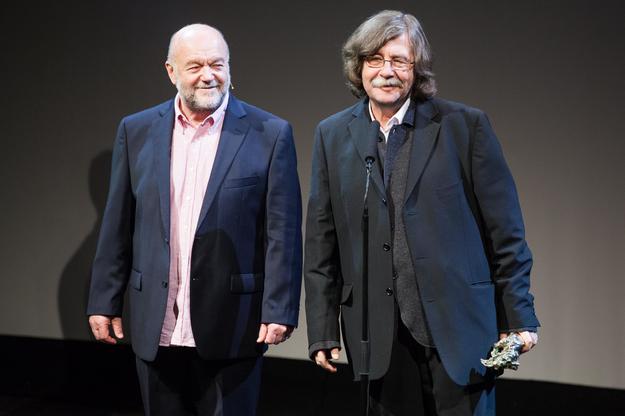

Godár (R) with singer Peter Lipa, receving the SOZA awards 2011-2012. (source: SITA)

Godár (R) with singer Peter Lipa, receving the SOZA awards 2011-2012. (source: SITA)

Godár with singer Iva Bittová (source: TASR)

Godár with singer Iva Bittová (source: TASR)