The current situation in most bachelor degree programs in Slovak and European universities presents prospective students with some surreal challenges.

Perhaps the biggest is choosing – and being accepted to – the right program at one of thousands of universities. Every year, high school graduates frantically search forthat program. But this is odd. Of the broad array of subjects they have studied in their thirteen years at school, they are forced to choose just one upon which the rest of their lives will be built. What if they discover after one semester or year that they have chosen the wrong one? They will probably have to apply to a new program and start all over. What a waste of time, energy and money.

Another challenge is posed by the learning style used in undergraduate programs at the vast majority of European universities, the lecture-exam model. New undergrads go from relatively small classes in secondary school to large lectures of fifty or even a hundred students, passively listening to a professor or instructor talk for ninety minutes. At the end of the semester, there’s an exam – often requiring the exact duplication of what was said in lectures, word for word. There is little to no interaction between the students and the instructor other than during the exam. Feedback on assignments is rare. There is little or no thought of honing critical thinking skills, or any of the other soft skills desired by future employees. What a betrayal of the potential of a young person who is at their prime intellectual capacity.

Even prominent and highly ranked European universities suffer from the same conditions. University rankings do not include teaching as a criterion for excellence. Instead, they give points for prominent faculty, research, publications, the quality of PhD studies, and technical and administrative facilities. There are no points for how much, or how well, bachelor program instructors teach. In fact, university teachers are hired based on their PhD degree and publications, not teaching skills. And since most countries link state funding to the number of students enrolled, as many as possible are accepted, resulting in first-year classes with a hundred students listening to someone who, most likely, has never had any pedagogical training.

Sadly, many Slovak high school graduates – and their parents – look for quality education elsewhere in Europe, believing it is surely better than in Slovakia. Each year, thousands leave to study abroad, most often in the Czech Republic. Yet, even though there is some truth to the quality of university education here and abroad, in many ways, there is little difference. Just like in Slovak schools, the majority of European undergraduate programs use the lecture-exam model, catering more to their professors’ research capacity and goals than to their students’ learning and growth.

Liberal Arts Studies

Fortunately, there is an alternative bachelor model slowly growing in Europe – liberal arts studies. Liberal arts differs from traditional European undergraduate education in every aspect:

Students do not have to choose their major (program) immediately but eventually decide based on their ability and interests.

Classes, or seminars, are small (max. 25 students) to provide the opportunity for discussion during every class.

The faculty are offered pedagogical training at teaching and learning centers to work on their teaching skills.

The teacher is there for students and not vis-versa. Hence, discussion, interaction, and feedback are valued both inside and outside of class, every class, every week of the semester.

Extracurricular activities are encouraged and supported, preparing students for their further studies and employment through communication, leadership, teamwork, and problem solving.

The medium of instruction is English, the current lingua franca that opens doors anywhere in the world.

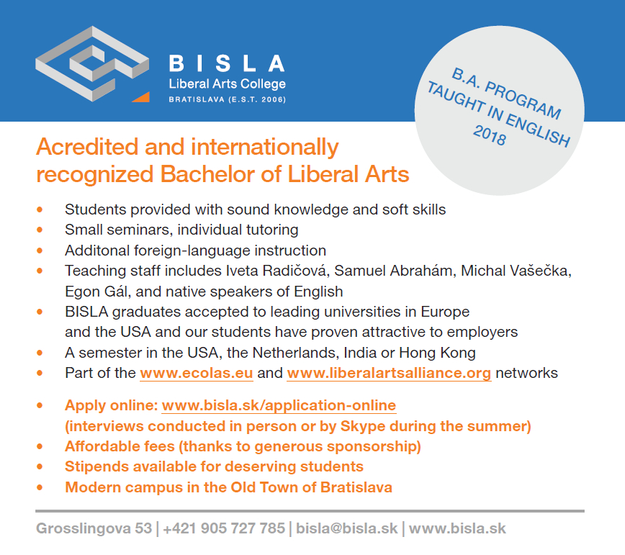

Bratislava International School of Liberal Arts (BISLA), the only liberal arts school in Slovakia, has been offering such a bachelor program for over a decade with its graduates as proof of its quality. Its students have opportunities to study at its sister liberal arts institutions around Europe who are all part of the European Colleges of Liberal Arts and Sciences (ECOLAS) network – also based in Bratislava – and pride themselves on ensuring the best undergraduate education possible for the 21st century, while committed to improving undergraduate education in Europe. After all, it is our young people who lose out when the educational system is more concerned about rankings than about learning.

So, how does the university you (or your child) have applied for or been accept to stack up? Does it meet the criteria (1-6) above for quality education? For the money, time, and effort invested, our young people deserve a quality education, like the one a liberal arts program can provide.

Associate Professor Samuel Abrahám, PhD

Rector of BISLA

Executive Director of ECOLAS (www.ecolas.eu)