Panenská Street, a dead-end road lined with cars and shabby and renovated houses from past centuries in Bratislava's city centre, used to be a place where artisans and winemakers ran their businesses back in the day.

In recent years, life has been returning to the quiet street and most of the houses again, reflecting the diversity that the Slovak capital was once known for. A legendary bookstore, German cultural centre, gay bar, small stores and cafés, and different churches all co-exist in harmony here today.

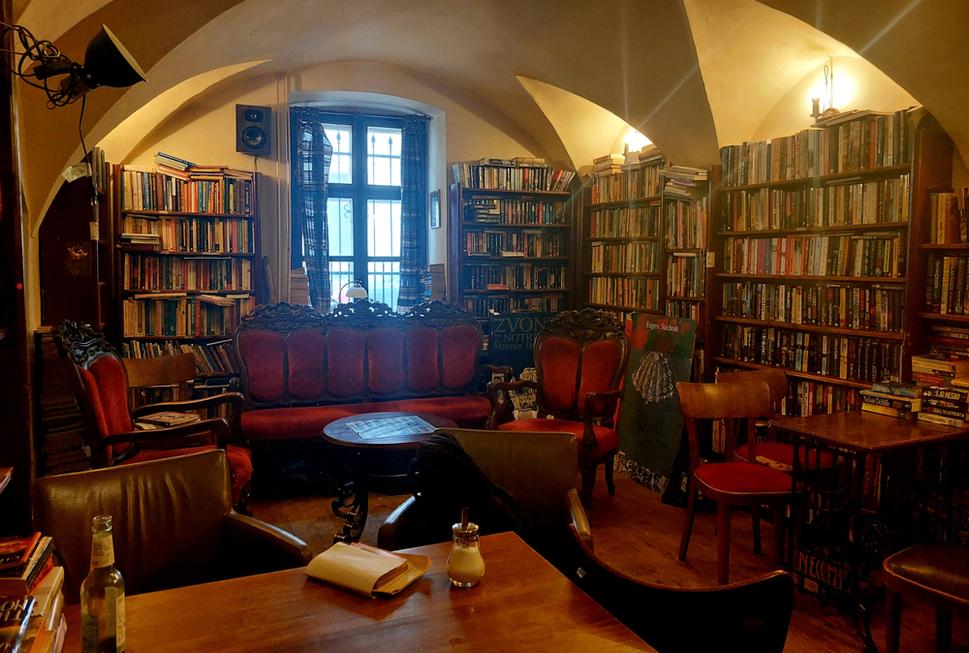

Next to the small Lutheran church nestles Next Apache, a popular café whose name refers to and sounds like the Slovak phrase “nech sa páči”, meaning “here you go” in English. Ben Pascoe, an English teacher from Canada, opened it for expats in a former storeroom in the early noughties, selling not only drinks but also English books.

“Every café was the same at that time,” he recalls, sitting by a shelf stacked with books in the homey surroundings, “We were something much different.”

Pascoe used to buy the books, often spy and crime novels, on his regular trips to Canada, as Bratislava bookshops had only a tiny selection of English books at that time. Today, he is glad he doesn’t still have to travel to Canada with an extra empty bag to fill up with things he cannot find in Bratislava. With more local bookshops now offering books in foreign languages, the English books at the café make nice decorations for the customers, mostly regulars, who come here more for the drinks.

“Thank God we sell coffee and alcohol,” Pascoe laughs.

His clientele has also changed. It’s locals rather than expats or tourists who frequent the place. “You don’t find this by chance. You have to know to come here,” he says about the café and the street situated just a stone’s throw from the Presidential Palace.

Zuzana Čaputová, the current Slovak president, has also visited the venue, Pascoe reveals.

Land of no smiles

When Pascoe started the business almost two decades ago, it was a time when the era of mafia groups was nearing its end and he, luckily, did not have to pay any protection money.

“We often joked that it was because there were books here, that people were scared of knowledge,” the Canadian says.

However, a moment that looked like a scene from a crime show happened in 2019 when the police raided Pascoe’s café, a venue popular with artists, journalists and politicians, during an investigation into how journalists were being spied on. They found no wiretapping devices, and it is water under the bridge for Pascoe today.

The education and business graduate found himself in Bratislava for the first time in 1999, a year after the autocratic prime minister Vladimír Mečiar was ousted, and he has stayed since.

The Canadian still remembers an FAQ paper about Bratislava given to him by his then employer on his arrival that said: don’t be surprised if you don’t see a Tesco worker smiling. As Pascoe recalls, the paper further explained that if a foreigner made as little money as the Tesco worker, they wouldn’t smile either. He himself then earned about 200 euros, less than the average wage of 356 euros in 1999. Since then, the Slovak average wage has more than tripled.

Initially, the Canadian was supposed to teach English in Prague. “I lasted a few weeks there,” he admits, explaining that the Czech capital was too big for him and so he decided to move to Bratislava. “It was harder to get people here, so I took a chance.”

Today, the private English teacher jokes there won’t be much work for him in the future as local people’s English is getting so much better.

“If you run into the police, they are able to help you in English a little bit,” he argues. Many expats might not agree, but Pascoe stands by his word. “You think it’s bad now? You should have it seen before,” he says, underlining that more information, including menus, is available in English. “We used to joke that if you need help, find someone with a backpack and looks young – they’re able to speak English.”

Nevertheless, the Canadian, who is now fluent in Slovak, admits that speaking a little bit of Slovak opens a lot of doors.

Building change

The capital has also evolved in many ways – except for the shabby main railway station. High-rising buildings have sprouted up, the city has a new bus station, the renovated Slovak National Gallery has reopened after several years, city services and public transport are better, and opportunities are wider, though the city has also gotten more expensive.

“In the past, Bratislava was known for get off the boat, spend an afternoon here, and go back on the boat and get out of the city,” Pascoe says, “Now tourists don’t have to.”

Still, one of the best things about Bratislava remains how accessible Vienna is, the Canadian jokes, stressing that he sees the location of the Slovak capital and the country itself as a huge advantage that allows people to reach all kinds of places – be it forests, castles or bigger cities like Vienna or Budapest – within just a few hours.

Even as the city has become more attractive for tourists, the Bratislava resident appreciates the fact that city hall has not forgotten about local people, and that starting a business in Slovakia is easier.

“The thing that’s changed for me the most over the years – we don’t have to go to the centre and pay the expensive tourist prices, because outside of the centre there’s many nice places to go,” the Canadian says.

However, he would welcome more night buses and fewer motorised scooters – the latest trend – in the city.

While he is not a politician who can directly change things, despite being a foreigner Pascoe has been closely following national and local politics for many years. “Because this is my home now, it’s important to me what goes on in politics,” he claims.

When he arrived in Slovakia, he says he noticed how widely accepted corruption was. “Now, it’s not. People do stand up,” he believes.

This foreign observer of local politics also feels that life in Bratislava seems to be getting better with each new mayor, but he has some suggestions on how the city’s management could be further improved: he would get rid of several different layers of local and regional government. In total, 317 local councillors sit in the city and there are 17 borough councils. By comparison, 150 lawmakers sit in the national parliament.

Although Pascoe does not plan on joining local politics for now, he is glad he can still be a part of the changes in Bratislava as a resident. On Panenská Street businesses work together, he says, to make the area much more interesting and inviting.

“I’m very happy to be home here, and I want to make Bratislava a better place,” he says.

This story was produced in partnership with Reporting Democracy, a cross-border journalism platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

Canadian Ben Pascoe runs a cafe in Bratislava's Old Town. (source: P.D. )

Canadian Ben Pascoe runs a cafe in Bratislava's Old Town. (source: P.D. )

Next Apache is a safe place for LGBT+ community. (source: P. D.)

Next Apache is a safe place for LGBT+ community. (source: P. D.)

Next Apache, housed in a light-yellow house on the left, is located on Panenská Street in Bratislava. (source: P. D.)

Next Apache, housed in a light-yellow house on the left, is located on Panenská Street in Bratislava. (source: P. D.)

Next Apache is also a used bookstore. (source: P. D.)

Next Apache is also a used bookstore. (source: P. D.)