I regularly go to the gym, go cycling, swimming and hiking. But running is not my cup of tea. I have not run, except to catch a tram or bus, since my school years. Yet recently, I enrolled for an almost 10-km run.

I decided to run to commemorate the 42 people who were killed at the Iron Curtain between former Czechoslovakia and Austria during their attempts to flee the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1948-1989.

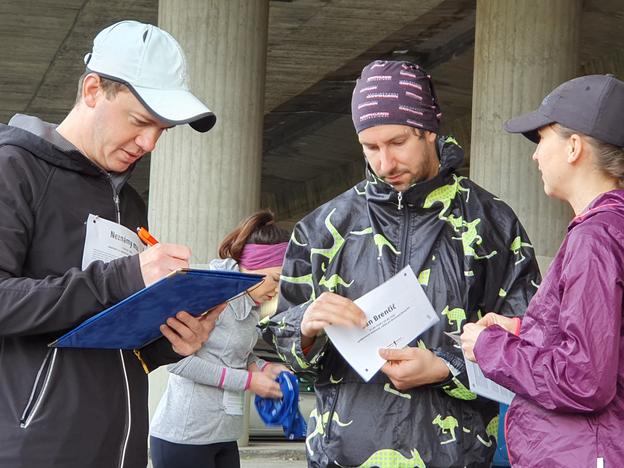

Keen runner Milan Čupka, who likes running along the former Iron Curtain near Lafranconi Bridge on the Petržalka side of the Danube, organised the Freedom of Movement event. Three decades ago, only border guards walked the narrow road, in some spots just a metre or two from the border. Today, people can freely cross and walk into the neighbouring Austrian fields.

Border guards would have fired at anybody who tried to run this road 30 years ago, using live ammunition. The communist leaders were always on about the happy and well-off lives we were living here, but they surrounded the whole country with barbed wire charged with lethal high voltage. Not to prevent people from the “decaying West” from entering, but to keep its own citizens inside.

More than 400 people were killed at the Czechoslovak borders with the West between 1948 and 1989. They were either shot dead, died blown apart by mines, electrically shocked or even torn by dogs trained to lethally attack intruders.

I ran for Mária Rozmaňová

At the start of the run, each participant received a piece of paper with stories of one of the 42 people instead of numbers. Mine was Mária Rozmaňová. As a 44-year-old, she attempted to escape as one of a group of 19 close to Jarovce, now part of Bratislava, on December 9, 1952. By then there was barbed wire on the borders, not yet charged with lethal electricity. To get out, it was necessary only to avoid patrols, draw apart the wires, brush past and run to cross the border.

Mária Rozmaňová was not lucky. The border patrol spotted her group and opened fire. They fired 459 projectiles from subguns and 90 projectiles from rifles. Five people were killed, including Mária Rozmaňová, and two injured. Six of the intruders were detained and six managed to escape.

I pinned the story on my back, feeling a little bit like the target of the former border patrol, and set out for the run. Memories immediately started to pop up in my mind.

Actually, I never saw the actual barbed-wire fence. Born in 1968, just a few days before the Warsaw Pact armies invaded Czechoslovakia, I grew up under what was known as the normalisation process that sent the country into its old totalitarian rut.

My life did not differ from the lives of thousands of others. My parents, even though they were not members of the party, made sure not to stand out in the crowd. That could have endangered their careers, but also impact the lives of my brother and I. The children of rebellious parents were not allowed to study in the field they wished, or they could do it only after first working in blue-collar jobs.

I went to a technical high school and then a technical university. I did not dream of becoming an engineer, but these were schools, where I, as a girl (thanks to gender quotas) and with my parents’ contacts, had sound chances of getting in. Law or medicine were only for the well-connected, or those with better marks.

I found my studies fairly interesting and never had any problems with maths, physics or technical subjects. I feared most subjects, like History of the International Revolutionary Movement (MRH) and Political Economy, and then the school-leaving exam from Marxism-Leninism. But I’m sure that if I could have freely decided, I would have picked a different field of studies.

Of course, I was thinking about what would come next in my life. Like any young person, I was idealistic, even though the reality was grey and double-faced. It was a period for pretending. Different things were said officially from what was said at home. Some of my uni classmates applied to become party members, even though they did not believe in the regime at all and did not even hide it. It was easier to become a party member during one’s studies than as a university graduate. There were quotas, and the number of new party members with university degrees had to match the number of new blue-collar members. A university diploma in combination with a party membership enabled people to climb faster up the career ladder.

My vision of my life after graduating from uni was rather dull: to work somewhere as engineer. I did not expect the work to be exceptionally interesting. I thought I would get married and have children and, as I call it today – emigrate within myself. Such emigration means living in one’s own small world, living as happily as possible, with one’s relatives and friends. Reading forbidden books would be my biggest rebellion, like Milan Kundera or Dominik Tatarka, along with listening to forbidden musicians like Karel Kryl or attending theatrical performances just narrowly escaping censorship like those hopelessly sold out shows by Milan Lasica and Július Satinský with their unforgettable anti-regime subtext.

I did not ponder emigration to the West. I was afraid, apart from the act of fleeing itself, whether I would manage to make a living abroad. Also, if I emigrated, my relatives would have been persecuted. Was I a coward? I don’t know.

I also could not imagine, as an ordinary person without any contacts, at that time much-needed, going through the bribing procedure to get special permission to travel to the West. As a result, I had expected to travel only to the Eastern Bloc countries, with a holiday in half-prohibited Yugoslavia to be the height of my travels. Thus, having a look at Austria, which was literally a few metres beyond Bratislava, was completely outside my imagination, even though we did listen to Austrian radio (especially the Ö3 single charts for me) and watched Austrian TV (a highlight for me were their colourful ads, strongly contrasting what was on shelves in Czechoslovak shops).

The fall of the regime came when I was in the fourth year at university, and everything changed. The borders opened and since then we can freely travel needing only money to do so – something unthinkable in the past.

Epilogue

One of the strongest and most emotional moments of the run, which I, an untrained runner, mostly walked instead of ran, was meeting Dorota Kubinová. She waited for us at the fourth kilometre, near the replica of the barbed-wire fence, with tea and cakes. Her aunt was shot dead in the 1950s by border guards during an escape attempt.

Now to cross the border we only needed to fight our way through the bushes separating the road on the Slovak side and the Austrian fields. Like every time I cross the Slovak-Austrian border, either on bike or car, I realised how unthinkable that once was for me. Crossing this border has never become a matter of course for me.

About 50 people ran on November 17 to commemorate the 42 people who were killed at the Iron Curtain between former Czechoslovakia and Austria in their attempts to flee the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1948-1989. (source: Jana Liptáková)

About 50 people ran on November 17 to commemorate the 42 people who were killed at the Iron Curtain between former Czechoslovakia and Austria in their attempts to flee the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1948-1989. (source: Jana Liptáková)

Milan Čupka, second from the left. (source: Jana Liptáková)

Milan Čupka, second from the left. (source: Jana Liptáková)

At the start of the run, each participant received a piece of paper with stories of one of the 42 people killed at the Iron Curtian instead of numbers. (source: Jana Liptáková)

At the start of the run, each participant received a piece of paper with stories of one of the 42 people killed at the Iron Curtian instead of numbers. (source: Jana Liptáková)

To cross the border, the runners only needed to fight their way through the bushes separating the road on the Slovak side and the Austrian fields. (source: Jana Liptáková)

To cross the border, the runners only needed to fight their way through the bushes separating the road on the Slovak side and the Austrian fields. (source: Jana Liptáková)