October 31 is around the corner. For many in western Europe and the Americas it’s a time of fun and merrymaking. Getting dressed up, carving pumpkins, trick-or-treating. For many Slovaks, October 31 is simply the day before Dušičky, or All Souls Day. People return to their hometowns and light candles on the gravestones of their loved ones who have passed.

In Slovakia, as with much of the world, there’s a tension between the religious celebration of All Souls Day and the apparent satanic hedonism of Halloween. I spent a few years teaching in a Catholic school here, where any mention of Halloween was highly verboten. This somewhat mirrored my experience of Halloween growing up in Ireland.

The first few years I was at school, Halloween was celebrated in class by all of us putting on cheap plastic masks, eating monkey nuts and bobbing for apples. That was until Father Pearse, our parish priest and member of our school’s board of directors, came in and put a stop to our heathenism.

As long as I’ve been in Slovakia, adults have been celebrating Halloween in the form of parties in bars and clubs. Now it seems more and more children are being marketed to, with various children’s play areas and even language schools holding Halloween parties. While plenty of Slovak people love and embrace Halloween, I am very aware that there is a strong undercurrent here that opposes it.

In an effort to understand the thinking of the Slovak public about Halloween, I took to the internet. Many of these kids events are being advertised there, with some of them garnering highly negative reactions from some vocal sections of the local population. Not only are the standard religious motivations there, but also nationalistic and ethnic ones. Halloween is bad because it is satanic, celebrates death and monsters. It is also bad because it’s American. One I haven’t heard before now is that Halloween is bad because of its Celtic origin.

Halloween or Samhain?

Yes, Halloween has its roots in Celtic traditions. Specifically Gaelic. The feast of Halloween is a Christianised version of Samhain (pronounced Sow-wan), a harvest festival practised in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Like most folk festivals, it served a practical purpose; the year is about to enter its darkest phase, so gather your food and be prepared. It also provided an opportunity to pay respect to one’s ancestors.

The narrative applied to this change was that dark spirits began leaping out from caves that were portals to the underworld. The preponderance of ghostly spirits bounding around necessitated the lighting of bonfires to ward them away, as well as dressing up as monsters in order to fool them that you were one of their kin.Trick-or-treating can perhaps be linked to this practice. People give gifts to the dark spirits to move them away from their house, to the next. That the layer between this world and the next was weakened also meant that you might be closer to the good spirits of your loved ones.

These folk practices stayed with people in Ireland for generations, eventually melding with the Christian feast of All Saints Day, which was conveniently placed at the same time of year as Samhain. Christmas was also brought into the Christian fold in a similar way, from the Ancient Roman feast of Saturnalia.

The folk celebrations, transmuted into Christianity, followed emigrants to the New World. Over the centuries it has morphed into an almost wholly American affair, complete with ample opportunities for commodification - mass-produced costumes, decorations and sweets.

But that doesn’t mean it could not have its deep roots in Central Europe. The Gaels of the British and Irish isles were the descendants, remnants, of a European Celtic culture that was extant at the time of the rise of the Roman Empire. There were Celts all over the continent - even the territory of today’s Slovakia. Many of the so-called barbarians that the Romans tussled with (and eventually genocided out of existence) along their borders were in fact Celtic.

Celtic roots

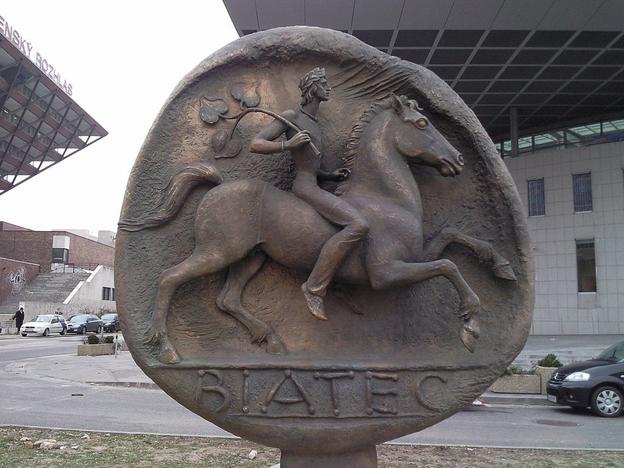

Evidence of Slovakia’s Celtic past can be seen in places like Smolenice, near Trnava in western Slovakia. Under the shadow of their beautiful castle there is a small recreation of a Celtic settlement there, dating back to the 6th century BC. The hill where Bratislava Castle is situated was also at one time settled by Celts. Even the Biatec coin, which we can see today recreated outside the National Bank of Slovakia in Bratislava, evidences this connection. Biatec was a Celtic king, believed to be of the Boii tribe.

Even the naming conventions of the region may shed some light on this forgotten past. The River Danube is believed by some to take its name from the Celtic goddess Danú. The River Morava, it is suggested, is related to the Gaelic words Mór and Abhainn, meaning “Big River”. Even one explanation put forward for the naming the city of Brno in Czechia states that it comes from the Celtic word for hill.

Did the early inhabitants living in the territory of what is now Slovakia celebrate Samhain like their Irish cousins? That’s hard to know due to the lack of written sources. But it’s not impossible that on an October night some 2,000 years ago, children sat, speaking something akin to modern Gaelic, around a fire in a smokey hut near the banks of the Danube. Wind and rain battered the wattle and daub walls of their houses as their elders explained to them that the darkening skies, falling leaves and dropping temperatures were being caused by mysterious spirits roaming the Earth. Maybe even the genocidal Roman soldiers themselves were seen as the same agents of darkness.