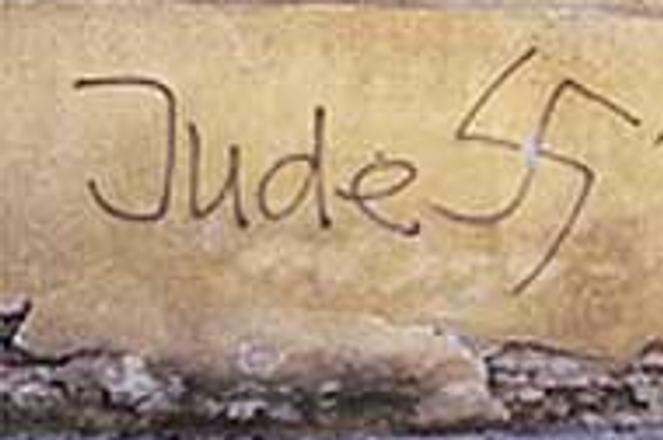

This anti-semitic graffiti, which in English means "Jews Out," is on a side street off Bratislava's Americké námestie, near a church and a high school.photo: Ján Svrček

Libyan diplomats in Slovakia made an upsetting announcement on August 8: Two of their sons had been attacked by skinheads in June. The diplomats also said that several other violent attacks against Arab students had taken place in January and February of this year.

Weeks before the Libyan announcement, a Chinese diplomat had been seriously injured by a gang of youths in Bratislava. Also in July, two British citizens of Asian origin were attacked.

Faced with increasing concern from the general public and diplomatic community about an apparent surge in hate crime, Interior Minister Ladislav Pittner took the opportunity last week to talk tough.

"I'm warning all skinheads that doing what they do or would like to do contradicts the law. They will be driven back hard [by the police]," he announced at an August 16 press conference.

But despite the minister's threats, human rights activists and observers warn that far too little has yet been done by the police to rein in hate crime. Police statistics do not accurately record the problem, nor do judges always acknowledge it. The failure to classify and deal with crimes as racially motivated keeps them from being dealt with effectively, human rights activists say.

According to official statistics provided by the Bratislava-based Police Corps Headquarters, just eight of the total 2,029 physical attacks on civilians during the first half of 1999 were racially motivated.

In Bratislava, only one racially motivated crime took place during that period, said Marta Bujňáková, a police spokeswoman. These numbers, however, contrast strongly with anecdotal reports from ethnic residents of Slovakia, who say that skinhead and other hate crimes are far more common.

Lack of reporting

Why hate crime is not effectively dealt with in Slovakia is a matter of debate. Victims and human rights activists claim that the police and the judiciary are not really interested in investigating the crimes and meting out appropriate punishments to the offenders. The police, on the other hand, claim the reluctance of victims to report such crimes keeps them from taking the necessary steps.

The "skinhead" type attacks which are reported, Bujňáková explained, usually follow a similar pattern. Assailants gather in groups of anywhere from a few to 15 or 20 people, and surround individuals, couples or small groups. Foreigners and people of colour are often targeted.

Some confusion about the racial motivation of such crimes arises because Slovak skinheads will occasionally just as eagerly attack "white" foreigners or domestic residents, Bujňáková said. "My husband was beaten up by skinheads on his way home at night," the policewoman revealed. "But it's difficult to identify the attackers, unless the person knows them personally, so the police rarely find the assailants."

Bujňáková claimed that if civilians do not report attacks, there is nothing the police can do about investigating these crimes and prosecuting the criminals. "That's the least they should do [report the attacks]," she said.

But human rights advocates said that blaming people for failing to report the crimes belies the real problem: that little is done when they do report them. Slovak Roma, for example, are often told that unless they can actually name their attacker, or provide a better description than "a guy without hair," the police will do nothing about the case, said Claude Cahn, publications director at the European Roma Rights Center in Budapest.

"The cases are seldom reported, because when you make a report you can be almost sure that no one will step into the case [to investigate]," said Igbo Anusi Columbus, an activist with the Info Roma human rights foundation. He added that, according to the information of human rights organizations, up to 85% of all skinhead attacks were not reported to the police.

"They (the police) just don't take the attacks seriously," said Columbus, who himself has been attacked several times. He said he had only once reported an attack to the police.

Shortcomings in state legislation and a lack of desire on the part of law enforcement authorities to pursue difficult cases also make it near impossible to prove a racial motive, human rights activists and legal experts say. According to the law, a violent act is classified as racially motivated if the accused confesses that it was, or if there is "other evidence of the racial motive," said Ján Hrubala, a former judge who is now a human rights activist.

Skinheads usually deny the racial or nationalist motives of their acts, Hrubala said, while little is done to assemble other types of proof, even in what seem to be the most obvious of cases.

In 1996 in Banská Bystrica, for example, a young Romany was brutally attacked by three skinheads who called him " nigger" and "filthy gypsy". When the case went to court, the judge ruled that an attack by a Slovak skinhead against a Romany person could not be racially motivated, as both the assailant and the victim "are part of the same [Indo-European] race."

The strange ruling has brought a certain degree of notoriety to the Slovak court system and has underlined again how difficult it can be for a member of an ethnic minority to find justice in this country's court system, the Roma Rights Center's Cahn said.

"The ruling is an extremely embarrassing situation for Slovakia... and is indicative of the larger difficulties of getting justice in its court system," he said.

Gregory Fabian, a lawyer and consultant for the Vienna-based International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, said that another main problem was that Slovak legislation, including the Criminal Code, was not fully in compliance with international norms such as the UN Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and the Council Of Europe's European Convention of Human Rights, to which Slovakia was legally bound.

"For example, the Slovak Criminal Code does not give a specific definition of what constitutes a racially motivated crime," said Fabian. "And Slovak judges are still not very much aware of the international obligations."

The Criminal Code punishes "ordinary" physical assault with a maximum two-year sentence, although people convicted of "injuring someone's health due to their political convictions, nationality, race, religious or other beliefs" may be given heavier sentences.