Yukos' decline casts uncertainty over fate of Slovak pipeline operator Transpetrolphoto: TASR

SLOVAKIA might want its Transpetrol shares back just two and half years after the Slovak government sold a minority share of the crude oil pipeline operator to Yukos, Russia's second largest oil concern.

Economy Minister Pavol Rusko said that Slovakia would do everything possible to regain Yukos' 49-percent share in Transpetrol. The Economy Ministry still owns 51 percent of the former state-owned pipeline company.

Yukos remained reserved over the news.

In a memo to The Slovak Spectator, Yukos said, "We have learned from the media about the Slovak government's intention to regain the 49-percent share in Transpetrol. So far we have not received any word from the Economy Ministry in this regard. We will take a stand after receiving an official statement."

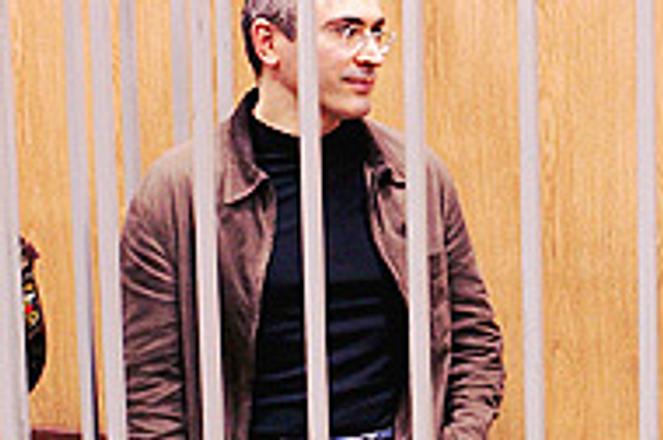

Yukos, led by entrepreneur and 44-percent owner Mikhail Khodorkovsky, hit tough times when Khodorkovsky was arrested for alleged tax fraud in 2003 and resigned.

In 2004, the company was charged €2.64 billion in back taxes. Recently, the Russian government slapped another tax suit against Yukos, bringing its liability to €5.2 billion.

Yukos will hold a shareholder meeting December 20 to decide whether to file a bankruptcy proceeding or liquidate the firm.

Minister Rusko told the press that the Ministry wrote a letter to the Russian government expressing its unambiguous readiness to negotiate the return of Yukos' Transpetrol shares to Slovakia. Rusko said he would like to see the fate of the shares determined by Russian authorities with little Slovak intervention.

Transpetrol was tight lipped when commenting on the developments.

"The repurchasing the 49-percent share of Yukos in Transpetrol by the Slovak government is a matter of agreement between the two shareholders. The leadership of Transpetrol does not consider comments over the issue appropriate," Transpetrol General Director Štefan Czucz told The Slovak Spectator.

According to Rusko, Yukos faces almost certain insolvency, which would likely result in its return to state control.

The Economy Minister has not yet discussed the issue with ruling coalition partners but he claims that a decision about Transpetrol shares must be a top priority.

He implied that after regaining Yukos' stake, the Ministry would try to find a new strategic investor for Transpetrol, hinting that the Slovak government would consider selling more than 49 percent of its shares. However, keeping the shares in state hands is equally likely.

In October 2003, after the parliament passed legislation allowing the state to sell its majority stake in strategic companies, Rusko suggested that the Ministry planned to keep its 51-percent stake in Transpetrol.

The Slovak government sold its Transpetrol shares to Yukos for $74 million. Yukos took control of the 49-percent stake April 29, 2002, having secured the tender in December 2001 after competing with Slovak oil refinery Slovnaft.

Rusko thinks the value of the Transpetrol shares is more-or-less the same. There has been no public discussion about where the state would find the money to buy back the shares.

Assuming Slovakia regained YUKOS' shares, Rusko said the best thing to do would be to sell them directly to a new investor without announcing a new tender.

TRANSPETROL owns the Slovak portion of Druzhba pipeline.photo: Courtesy of Transpetrol

The legality of selling remains questionable. The state's contract with Yukos embeds a clause prohibiting either party to sell Transpetrol shares to a third entity without the approval of both parties for five years.

Analysts warn that if the contract did not include a clause permitting Slovakia first dibs on buying back the shares, Yukos might lend an ear to more lucrative offers.

Analysts also fear that Transpetrol could wind up in the wrong hands, turning the shares into a tool for economic blackmail.

Yukos had hoped to use the stake to gain access to western and southern European markets, as well as initiate a pipeline sea route to North America.

The Slovak pipeline network enjoys an advantageous position in the European crude petroleum market, giving Transpetrol leveraging power. The network consists of two routes - the Druzhba and Adria pipelines - both of which have favourable geographic locations and a relatively high transport capacity.

Druzhba was built on Slovak territory between 1960 and 1961. Its route starts in the Russian Federation and continues to the Czech Republic through Belarus, Ukraine, and Slovakia.

Druzhba's overall length in Slovak territory reaches 507 kilometres; beyond Slovakia's borders it stretches a further 2,280 kilometres. The throughput capacity of Slovakia's section is 21 million tonnes of crude petroleum per year.

The Adria pipeline covers just 8.5 kilometres in Slovak territory, starting in the Croatian port of Omishajl and leading to Hungary and Slovakia. It has an overall length of 606 kilometres and an annual capacity of 4.5 million tonnes. It connects to the Druzhba pipeline in Šahy-Tupá, in southern Slovakia.

The same year that Yukos took control of its minority stake in Transpetrol, Slovnaft complained to the Slovak Antitrust Office about the Transpetrol tender deal. Slovnaft alleged that Yukos, as an oil supplier that also controls pipeline distribution, could offer advantageous prices to itself to the detriment of other oil supply companies in Russia and the Caspian region.

Transpetrol has had its own share of controversy. The then-state-owned pipeline company made headlines in 2001 when it unexpectedly sold its stake in the former East Slovak Ironworks (VSŽ) to the Penta Group. Transpetrol was acting on behalf of its sole shareholder, the Slovak state

Former Economy Minister Ľubomír Harach had supposedly put the sale of Transpetrol's 21-percent stake in VSŽ on hold, saying the time was not ripe for the sale due to a sharp decrease of the share prices. Analysts agreed that the downturn was a result of speculation.

When the sale took place, it came as a surprise to many, including the VSŽ. Anton Bidovský, the VSŽ's boss, said that both the Economy Ministry and Transpetrol were aware that it wanted to buy its own shares back at Sk200 (€4.76) per share, Sk40 (€1) per share higher than the price paid by the Penta Group.

In mid 2003, authorities charged with investigating the sale halted its inquiries. Jozef Bernát, head of the special prosecutor's office, confirmed that investigators had failed to prove that any crime had been committed regarding the transfer of VSŽ shares to the Penta Group.