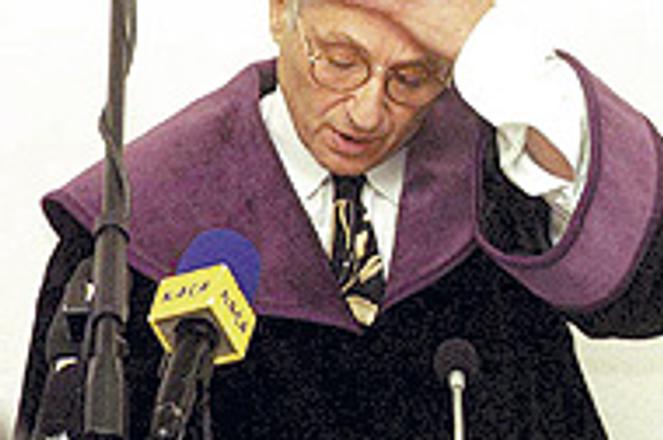

Tibor Šafárik is principally remembered for his "unique" decision in 1999.

photo: Archiv

WHEN THE election terms of 6 Constitutional Court justices expire on January 22, the court, whose function is to protect the basic rights and freedoms of Slovak citizens, will be left with only 4 justices of its full complement of 13.

Deputy Chief Justice Eduard Barány said the court should still be able to function under an emergency regime with this skeleton staff, but that it would be unable to rule on issues that require a plenary session of at least seven judges.

"The result will be an increase in unfinished business left over for the next justices," he said.

The blame for the delay in appointing replacement candidates has been laid squarely at the doors of parliament, which will try again to agree on a final Constitutional Court nominee at the end of January. That name, if selected, will make up the required complement of 18 candidates that must be presented to Slovak President Ivan Gašparovič before he can choose 9 new justices, possibly in February.

However, as in the past, the ruling coalition's habit of putting forward controversial nominees ensures that the election process will be anything but smooth.

The man the legislature will be voting on, Tibor Šafárik, gained the support of the ruling coalition only recently. Parliament already rejected him once, in October last year, but he is now back in the running under the patronage of the Slovak National Party (SNS).

MP Rafael Rafaj, head of the SNS caucus, said that Šafárik met the professional and moral criteria for a Constitutional Court judge, but other coalition MPs refused to comment.

Members of the political opposition regard Šafárik as unacceptable. They object to the decisions he made as a Constitutional Court justice from 1993 to 2000, especially in a notorious 1999 case where a Šafárik-led panel of three justices upheld a blanket amnesty granted by former Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar to those accused of the 1995 kidnapping of the son of former President Michal Kováč.

Ján Klučka, the former judge on Šafárik's panel who was outvoted 2-1 in the case by Šafárik and Justice Ľubomír Dobrík, told the Sme daily on January 15 that "[The Court's] radical departure from its own previous rulings was not based on any rational justification."

But Šafárik told The Slovak Spectator that he still stands by his 1999 ruling, and that he is proud of it.

"This whole mountain of objections against me isn't worth a thing," he said. "These feelings against me have a purely political basis. But none of this surprises me. These criticisms come from people who don't hold to the basics of democracy. And on top of that, the decision on the amnesty was made by the whole Constitutional Court, not just by me alone. Why then are they always criticising me? They act as if I'd privatised the Constitutional Court.

"Everything can be criticised. Even Christ can be criticised. But everything has to be in accordance with the law. This crusade against me has only one simple and fundamental purpose: to frighten me."

Decision time

The decision made by Šafárik's panel dealt with a complaint filed by the former deputy director of the Slovak Intelligence Service (SIS), Jaroslav Svěchota, who along with 15 other former colleagues complained that they were being prosecuted for a crime which, according to them, Mečiar had already amnestied.

While the SIS under the 1994-1998 Mečiar government denied having been involved in the kidnapping, Svěchota admitted to this reporter in an interview in spring 1999 that the SIS had kidnapped Michal Kováč Jr. He added that the kidnapping had been thought up by Mečiar, and that the command to carry it out had come straight from Ivan Lexa, who was director of the SIS at the time.

"As head of the counter-intelligence service, I fulfilled the three orders that I received. I interpreted them as was necessary," Svěchota said at the time.

Despite all the evidence that the SIS had been involved, including a statement to this effect by its new director, Vladimír Mitro, the Constitutional Court panel under Šafárik's leadership ruled that the sweeping amnesty granted by Mečiar applied to Svěchota's case, and ordered that the charges be dropped.

The decision was blasted by a group of Slovakia's leading constitutional and criminal lawyers, who, in an analysis they published in December 1999, pointed out the many legal errors that had been made in the proceedings.

These errors included the fact that Šafárik's panel had allowed Svěchota and his colleagues to appeal straight to the Constitutional Court before exhausting all other legal avenues, as required by Slovak judicial procedure. They also stated that the Šafárik panel had illegally extended its ruling on Svěchota's complaint to apply to other cases, above all the prosecution of former SIS Director Lexa.

The analysis concluded by stating that "the Constitutional Court, which is an organ established to protect the constitution, has in the abovementioned case actually violated the constitution and endangered its further stability. Its decision was an insult against natural justice, the principle of legal certainty and public trust in the law. The decision of the Constitutional Court returns Slovak society and Slovak law to the period before November 1989 as it is an illegal act and an abuse of public power."

Fears for justice

As the current parliament has made its selections for the next court, fears have arisen that the candidates are too closely tied to the ruling coalition, and that they may not be up to the job of protecting democracy in Slovakia.

"I'm worried that the court will cease to be balanced, and that its personnel composition will be the mirror image of the current ruling coalition," said former Constitutional Court Chief Justice Ernest Valko.

"That's very important, because in addition to protecting constitutionality, the court also sets the direction of Slovak society. It makes a huge difference what approach these judges take, whether they are socialist, liberal or conservative, just as it does in the US, for example."

The court's former chief justice, Ján Mazák, who resigned on September 30 last year, warned before leaving that "in order for the Court to continue to function as well as it has up to now, it is very important that the candidates chosen are fully capable of doing the job".

Mazák referred to the 1999 ruling of Šafárik's senate as "unique", a statement that Šafárik said he found offensive.

Šafárik has had a busy political career. In 1990 he unsuccessfully ran as the SNS' candidate for mayor of the eastern Slovak city of Košice. He was elected to the Constitutional Court in 1993 as an SNS candidate and served until 2000. In 2002 he ran for parliament, again as a member of the SNS, and became the party's shadow minister of justice. His long and close association with the SNS is another bone of contention for the current opposition, which argues that a Constitutional Court judge should not be closely aligned with any one party.

Šafárik ran for the post in October 2006, but received only 64 votes, short of the majority he needed in the 150-seat house. According to former Justice Minister Daniel Lipšic, if the ruling coalition supports Šafárik in January, it will be due to pressure from the SNS party.

Those already elected by parliament as possible appointees to the Constitutional Court include current Justice Minister Štefan Harabin, as well as current Constitutional Court judges Lajos Mészáros and Ľudmila Gajdošíková.