NOVEMBER 17, one of the red-letter dates in the Slovak calendar, is a holiday devoted to the memory of the 1989 Velvet Revolution. Each year it recalls among Slovaks warm memories of their liberation from the communist regime. But this year it has lost some of its shine, after several political parties started using the occasion to take swipes at each other. Their moves portend a tough, albeit relatively short, campaign before the general election in March.

Two of the leading parties on the Slovak political scene have already flooded the country with political billboards, although both deny that these represent the start of their campaigns.

Observers have rubbished the parties’ claims that the billboards are merely an attempt to commemorate the Velvet Revolution, and say that the messages in them clearly hint at the major difference of opinion over the EU bailout fund between the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKÚ) and Freedom and Solidarity (SaS).

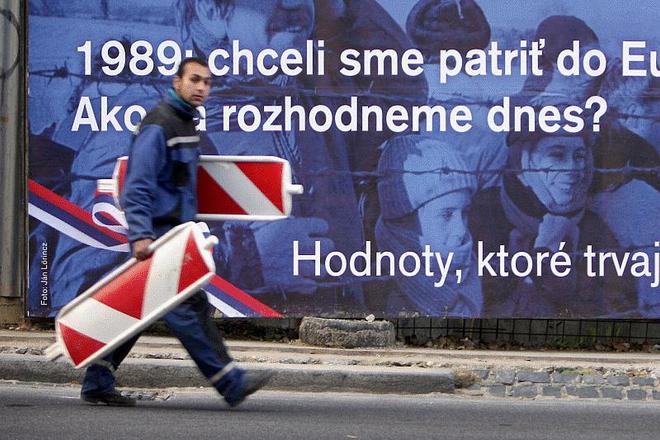

The SDKÚ was the first to launch its billboard campaign, citing the 22nd anniversary of the Velvet Revolution on November 17 as the reason. Seven hundred billboards have sprouted across the country featuring a blue-toned picture of people behind a barbed-wire barrier, saying “1989: we wanted to belong to Europe. How will we decide today?”

While the SDKÚ denied that the billboards are part of its election campaign and said they are instead a commemoration of the November 17 events, observers agreed that they clearly hint at the party’s conflict with SaS over the EU bailout fund.

Indeed, SaS was quick to respond with 200 billboards of its own, which referred to the same anniversary but employed a contrasting slogan: “1989: we fought for freedom. Why should we let them take it away from us today?” SaS also denied that its billboards were a counter-campaign.

Days before the national holiday on November 17, however, SaS politicians openly clashed with SDKÚ and Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) politicians over celebrations of the anniversary. First, the SaS-nominated defence minister, Ľubomír Galko, complained that neither Prime Minister Iveta Radičová, who is a member of the SDKÚ, nor the chairmen of the SDKÚ, KDH or Most-Híd, the other governing party, had invited SaS politicians to a commemoration event taking place at the Slovak National Theatre historical building in Bratislava.

“We’re not worthy of that any more,” Galko wrote on his blog. “I see this as their attempt to take all the credit for November ‘89, bask in its eternal glory in front of the cameras, and re-write history.”

Radičová rejected Galko’s criticism and said the event was open to the public and that there were no invitations.

“Anyone who feels the need to come and take part is free to do so,” she said, as quoted by the TASR newswire, adding that she would greet SaS representatives personally if they came to the event.

“The fight for November 1989, about who its real inheritor is and about how its legacy should be interpreted, is very topical,” political analyst Miroslav Kusý said, adding that the time of year was merely a coincidence and that any other occasion would have been used to launch campaigning in much the same way.

Right vs. right?

The November 17 bust-up demonstrates one feature of the campaign that will precede the March elections: this time around the centre-right parties will not stand united against Smer, as they did in 2010 and before.

Although Smer and the centre-right parties still remain the main rival groups in the fight for voter support, clashes are also expected between SaS, the party which chose not to support the European bailout mechanism and thus helped the Radičová government lose a vote of confidence in parliament last month, and the other governing parties: the SDKÚ, the KDH and Most-Híd.

Political analyst and president of the Institute for Public Affairs (IVO) Grigorij Mesežnikov expects the centre-right to start what he called an ‘interpretation fight’ over who was responsible for the fall of the Radičová government. The November 1989 billboards are a part of this interpretation fight, which started after the ruling coalition fell apart, he noted.

“It shows that the competition between the SDKÚ and SaS will be among the main topics, and that centre-right voters now find themselves in a situation of wider selection possibilities,” Mesežnikov told The Slovak Spectator.

The centre-right parties will no longer maintain the moderate approach that they pursued in 2010, when they refrained from attacking each other, Mesežnikov opined.

“Nowadays we cannot expect any such moderate approach, and we can already see aggressive attacks between them,” Mesežnikov said.

Mesežnikov also predicted that although the centre-right parties will fight for each other’s voters harder than they did in the previous election, with each attempting to become the leading party on the right, “there is still much more that connects them than divides them”.

Inactive activists

Another contrast with the 2010 campaign is that the centre-right parties seem unlikely to enjoy the support they previously received from civic movements and activists in their campaign against Robert Fico, the leader of the Smer opposition party.

The voices of civic activists and movements were heard very strongly in the 2010 campaign. They were raised mainly against Robert Fico and the populist-nationalist government he then led, and observers agree that they contributed very significantly to the subsequent change in government and the rise of Iveta Radičová as prime minister.

The biggest of these campaigns was definitely the one launched by Martin “Shooty” Šútovec, a cartoonist for the Sme daily, who collected tens of thousands of euros in the form of donations from friends and concerned citizens who wanted to see a cartoon he had drawn – depicting as bandits the three heads of the then-ruling coalition, led by Fico – appear on large billboards throughout Slovakia.

But activists like Shooty do not seem keen to help the centre-right this time around, after its failure to maintain a stable government.

“[The centre-right parties] do not deserve to have citizens do anything for them,” Shooty told the Sme daily, adding that they had wasted a great opportunity and he wished them only a cold shower in the elections.

1989 on a billboard. (source: SME)

1989 on a billboard. (source: SME)