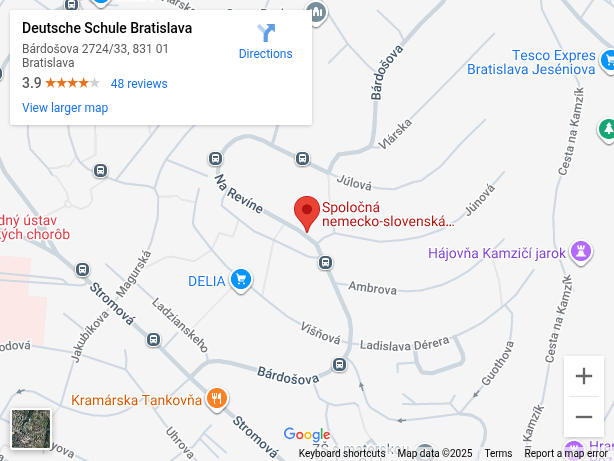

On the Revín hill overlooking the Slovak capital, a metal dome now turns quietly toward the heavens. Inside sits the city’s newest – and only – public observatory, a modest yet striking addition to the German School in the Kramáre neighbourhood. Opened in April 2024, the project is the unlikely product of a determined parent, a community-wide fundraising effort, and more than €200,000 collected from families and sponsors.

Its ambassador is Ivan Bella, the first Slovak astronaut.

For a city that has long lacked a planetarium or observatory, the facility is more than just a telescope under a dome. It is a public invitation to the night sky.

“From the very beginning we wanted it to be an observatory not only for this school, but for the whole of Bratislava and its surroundings,” explained Sven Rossbach, the parent behind the idea, to Postoj at the time of the opening.

Observatory vs. planetarium

Observatory: A facility with telescopes for studying the real night sky. Visitors look at actual stars, planets and galaxies.

Planetarium: An indoor theatre with a dome where projectors or digital systems simulate the sky. Visitors watch shows about space and astronomy.

Filling a void

Bratislava holds the unfortunate distinction of being the only EU capital without a public planetarium or observatory – a source of frustration for astronomy enthusiasts. The nearest observatory, operated by Comenius University in Bratislava, is located in Modra, a wine-making town about 30 km from the capital.

A long-promised riverside planetarium was scrapped at the eleventh hour after Mayor Matúš Vallo, backed by the city parliament, redirected its funding elsewhere in 2023. Instead, the mayor traded the project for a park and preliminary documentation for the Plato Staromestská development – a scheme for which he has yet to explain how it will be financed. Vallo reportedly argued that a planetarium is not something Bratislava needs.

“Many people were very angry,” astronomy enthusiasts Marián Psár and Matúš Tondriška recalled on the Spectacular Slovakia podcast.

When the idea of building an observatory at the German School was born, Rossbach approached Mayor Vallo for financial assistance, but Vallo refused to support the project. “We also held discussions with the mayor, but there was no interest on his part in taking part in this project,” Rossbach told Postoj. As the conservative daily notes, neither Vallo nor any other city official attended the opening of the observatory.

The German School observatory does not erase the absence of such a facility in the capital, but it goes some way toward addressing it: a professional-grade instrument housed in a rotating dome, open not only to students but to anyone curious about the stars.

The equipment is straightforward but effective. A solar telescope allows visitors to study the Sun’s surface, while the “go-to” tracking system locks onto planets, clusters, and binary stars, following their arc as Earth turns.

More than stargazing

The dome is open to the public, with sessions bookable online and guides available in English. Among them are Psár and Tondriška, best known for their Slovak-language podcast Slnečná zostava (“Solar Gang”). Their dry humour and gift for explanation help make the cosmos accessible.

School groups arrive during the day, when the telescope is turned on nearby landmarks — the hilltop Slavín Memorial, for instance — to demonstrate its power. Events for tourists mix science with lighthearted space trivia and team-building exercises.

The challenge of city skies

But stargazing in Bratislava is never ideal.

“From the centre of Bratislava you might see only 50 stars — the brightest ones. But travel a few hundred kilometres away and thousands become visible,” Psár and Tondriška told The Slovak Spectator. Kramáre’s higher elevation helps, but weather and the turning of the seasons still dictate what is seen, according to Psár and Tondriška. Planets appear and vanish; clusters and double stars remain a constant fallback.

“We are always half-joking that we wait for a blackout in Bratislava, just to see a truly clear sky,” they said.

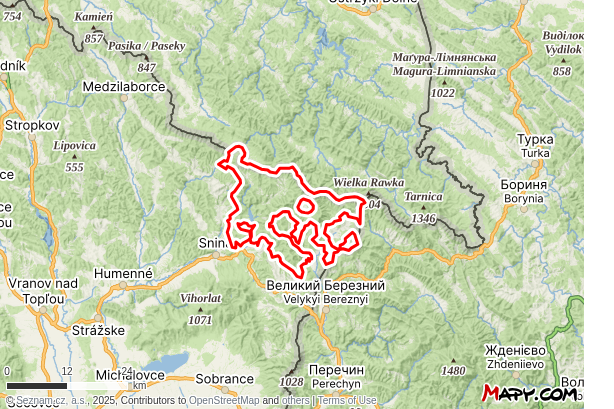

If the city’s skies disappoint, Slovakia’s countryside offers compensation. Poloniny National Park, near the Polish and Ukrainian borders, is one of Europe’s most celebrated dark-sky reserves, where the Milky Way spreads out in full clarity. “Dark sky reserves are rare in Europe because of light pollution,” Psár and Tondriška noted. Other Slovak dark-sky reserves in Kysuce and Malá Fatra, both in northern Slovakia, also draw stargazers to organised tours and lectures.

Poloniny National Park:

Cities such as Prešov, Košice, and Hlohovec already maintain observatories and planetariums.

For Bratislava, the new dome marks a modest but meaningful step. Organisers plan to expand its educational programmes and tourist offerings, ensuring it becomes not only a scientific outpost but part of the city’s cultural fabric.

For residents long deprived of a place to look up, and for travellers who want something beyond the castle and the cafés, the German School observatory offers a rare view of the cosmos — a reminder that even in a crowded, light-filled city, the stars are still there.

“What you can see differs from night to night, depending on the weather,” Psár and Tondriška concluded enthusiastically.

The new observatory at Deutsche Schule (German School) Bratislava (source: Marek Harman)

The new observatory at Deutsche Schule (German School) Bratislava (source: Marek Harman)

Astronomical observatories of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in the High Tatras (source: TASR - Veronika Mihaliková)

Astronomical observatories of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in the High Tatras (source: TASR - Veronika Mihaliková)

An amateur observatory at the primary school in Sobotište, Senica district, on Wednesday, 14 May 2025. (source: TASR - Martin Medňanský)

An amateur observatory at the primary school in Sobotište, Senica district, on Wednesday, 14 May 2025. (source: TASR - Martin Medňanský)

An observatory and a planetarium in Prešov, eastern Slovakia (source: TASR - Maroš Černý)

An observatory and a planetarium in Prešov, eastern Slovakia (source: TASR - Maroš Černý)