Even though Slovakia is not considered a low-wage country anymore, local wage costs are still far lower than in countries further west. While it will be years until this gap is closed, Slovakia should prepare and focus more on innovations and R&D as these bring also the need for more educated labour and higher wages. Findings of a recent remuneration survey show that the information and communication technology (ICT) sector offers salaries 22 percent higher than the Slovak market average. But apart from the sector the final total on the payslip depends on the region where they work and also on their gender.

ICT, pharma and banking jobs pay best

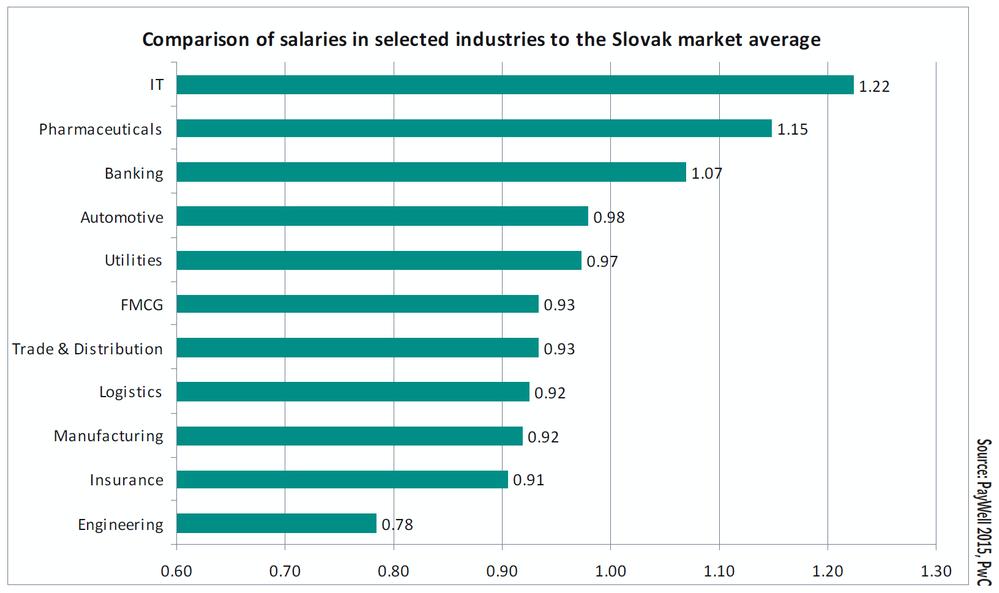

The ICT sector offers the best salaries to its employees, more than one-fifth higher than the Slovak market average, according to PayWell 2015, a survey of Slovak companies by PwC that included 290 companies from 18 industries. This year, ICT surpassed the pharmaceutical industry for the first time as the highest paying field. Salaries in the banking sector are also above average. The lowest paid workers are in engineering, at 22 percent below the market average.

Base salaries in the automotive industry were higher than in the energy industry, compared to last year, while there was a slight increase in base salaries in ICT and banking, said Peter Lackó, senior manager and leader of HRS department in PwC Slovakia.

In 2016, Slovak companies plan to increase base salaries by 2.9 percent. Employers were planning a 3.2 percent raise in 2015, but according to PayWell the actual increase amounted to just 2.8 percent. In accordance with PayWell, the highest salary increases in 2015 were in the insurance and automotive sectors. The lowest salary growth was reported in the energy industry. In 2016, the highest salary growth is planned in the service and ICT sectors. The lowest salary increase is planned in banking and energy sectors.

“Based on our experience from recent years, companies are being fairly cautious when planning their future salary increases,” said Patrícia Šimák, PwC HRC manager. “Actual increase may be higher or lower depending on the company’s results and we have also noted significant differences between sectors.”

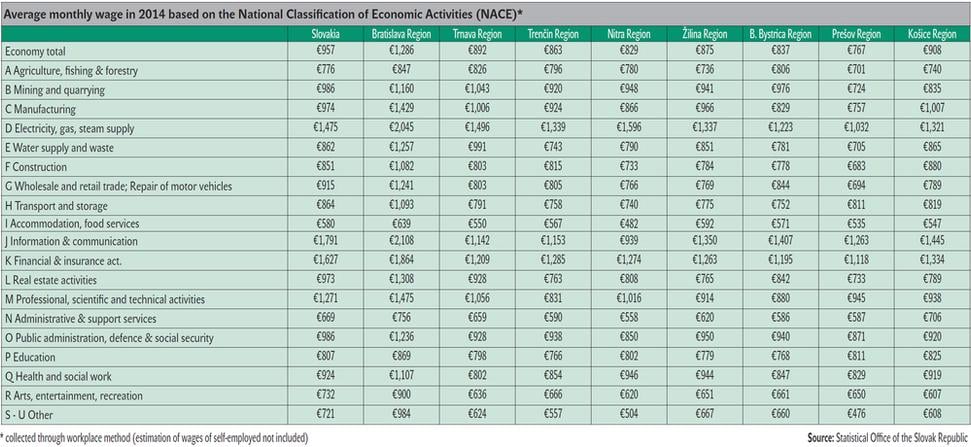

The PayWell survey confirmed once again that the highest salaries are in Bratislava and west Slovakia. The level of guaranteed salaries in west Slovakia is just 14.7 percent lower than in Bratislava. East Slovakia is just behind west Slovakia (16.5 percent less than Bratislava), followed by central Slovakia (16.6 percent less than Bratislava).

Labour costs grow but still low

Even though labour costs in Slovakia grow by a pace exceeding the average of the European Union and the eurozone, they still remain low in comparison with older EU members. More forecast that they will continue to increase and bring more sophisticated industry, more added value and jobs. But the country on the way from a low-wage country should not forget to develop a knowledge-based economy, experts warn.

Nominal hourly labour costs rose by 2.9 percent in Slovakia in the third quarter of 2015, compared with the same quarter of the previous year, Eurostat, the statistics office of the EU, announced in mid-December 2015. This growth exceeded the growth of 1.1 percent in the eurozone and 1.8 percent in the EU. But Slovakia lagged behind growths registered in other CEE countries with the highest annual increases registered in Latvia and Bulgaria (both 7.4 percent), Romania (7.3 percent), Estonia (6.1 percent) and Lithuania (5.7 percent).

The two main components of labour costs are wages and salaries and non-wage costs. In Slovakia, wages and salaries per hour worked grew by 3.1 percent and the non-wage component by 2.4 percent. In the eurozone and the EU wages and salaries per hour worked grew by 1.4 percent and 2 percent, respectively, and the non-wage component by 0.1 percent and 1.1 percent, respectively.

But while Slovakia keeps exceeding growth in the EU and the eurozone generally, its labour costs remain far below levels in the EU and the eurozone. In 2014, average hourly labour costs were at €9.7 per hour in Slovakia while it was €24.6 in the EU and at €29.2 in the euro area on average. However, this average masks significant gaps between EU member states, with hourly labour costs ranging between €3.8 (in Bulgaria) and €40.3 (in Denmark), Eurostat wrote.

There are labour costs comparable with Slovakia in Estonia (€9.8), Croatia and the Czech Republic (equally €9.4), while neighbouring Germany reported labour costs of €31.4 and Austria €31.5, in 2014.

Pointing to this difference, economist Vladimír Baláž from the Institute for Forecasting of the Slovak Academy of Sciences says that Slovakia still has very low wage costs.

“Of course, the situation is different compared with 20 years ago, when the average monthly wage in Slovakia was €150, but labour costs in Slovakia still belong among the low end, with the exception of Romania, Bulgaria and some Baltic countries” said Baláž, adding that wages in developed countries like Germany or Scandinavian countries are growing too, but at a slower pace than in Slovakia.

Labour costs in Slovakia have more than doubled over the last 10 years when they were at €4.1 per hour in 2004. Analysts and economists agree that Slovakia is not a low-wage country anymore.

“The change took place gradually, in various times in various sectors,” Robert Chovanculiak of the Institute for Economic and Social Studies (INESS) think tank and the Faculty of Economics at the Matej Bel University in Banská Bystrica told The Slovak Spectator.

Baláž ascribed part of the long-term growth of wage costs also to high inflation Slovakia experienced during its transition to a market economy, but he does not see growth in labour costs as a negative development.

“Of course, Slovakia cannot compete with Bangladesh, but developed countries have to compete with innovations and technologically developed products,” said Baláž, adding that only people with high wages and a good education can produce such result. The transfer to a knowledge-based economy is thus “wanted and proper” and it will also reflect in growing wages.

“And this is good, because growing wages then create a high prospective demand and new jobs,” Baláž said.

But he warned that in terms of the growth of wage costs there are several trends that meet in Slovakia.

“Wages increase also because of a lack of labour,” said Baláž, adding that while the local jobless rate is a bit above 10 percent, which compared with the rest of Europe is a relatively high unemployment rate, but that the natural jobless rate in Slovakia is estimated being between 8-8.5 percent as many of those people are considered to lack the necessary skills for full-time employment.

In terms of impact on the economy, high labour costs may mean that those manufacturing sectors based on cheap labour would depart for abroad.

“I do not see this as something wrong but as proper,” said Baláž, adding that developed countries went such a transition 20-30 years ago too. “Our task is to make the transition to sectors with a higher added value and thus also higher wages.”

But Baláž warned that this transfer is slow for now in Slovakia.

“Slovakia in terms of innovations and R&D is somewhere at the end of the EU train,” said Baláž, warning against the situation that happened in Portugal when it failed to arrive with innovations and R&D when the country became too expensive and investors moved their productions to eastern Europe.

Nevertheless, factors that will have the biggest impact on the future development are external ones as Slovakia is a small and open economy.

“When something happens in Germany or Italy, negative or positive, the impact in Slovakia is four times stronger,” said Baláž, citing macro-estimates that if the GDP decreases in Germany and other big countries by 1 percent, in Slovakia there would be a drop by 3 percent. If nothing special happens in the eurozone, years 2016 and 2017 should be favourable, the jobless rate should decrease and wages increase. This could also be in consequence of the demographic development with fewer young people arriving on the labour market who would ask for higher wages, Baláž explained.

Chovanculiak added that it is difficult to make predictions for the whole economy, but noted that in the upcoming years another carmaker, Jaguar Land Rover, will open its plant in Slovakia.

“Its demand for labour would further increase wages of workers in the automotive industry,” Chovanculiak said. In other sectors, much will depend on the quality of the business environment as well as external factors, that is the development of foreign economies.

Minimum wage

The one-party Smer government kept increasing the minimum monthly wage in Slovakia, from €327 in 2012 (when it took power) to €405 as of 2016. Prime Minister Robert Fico has already indicated that if his party is part of the next cabinet, the trend is set to continue.

“My vision is that if we were in the government and if Slovakia fared as well as we fare now, we would go closer, step by step, to the €500 level,” Fico told the TA3 news channel in early January 2016.

The government increased the minimum wage, by €25 per month, in 2015 with the hike effective as of the beginning of 2016.

“In this case, there is neither a winner, nor a loser,” Labour Minister Ján Richter said. “It’s important that people who work for a minimum wage will actually feel the increase in 2016.”

Profesia.sk, the biggest job portal in Slovakia, pointed out that Slovakia has now a higher minimum wage than the Czech Republic, where it is €365 per month and Hungary with €352. In Poland it is €445 while Austria does not have a general minimum wage.

The Institute of Financial Policy (IFP), a government think tank at the Finance Ministry, believes that the influence of the minimum wage in Slovakia affects only a small number of employees. The IFP estimated in its analysis from January 2016 that about 7 percent of employees with a standard work contract earn a gross wage within the interval +/-5 percent of the minimum wage. The share of employees earning the minimum wage oscillates depending on age, sector and region where employees up to 24 years of age, working in accommodation and catering services and in the Prešov Region earn the minimum wage most often.

The influence of the minimum wage is not equal across Slovakia, according to Chovanculiak.

“The minimum wage acts negatively especially in central and eastern Slovakia and on sectors, in which wages oscillate around it – retail sale, wholesale, hotels and restaurants and so on,” said Chovanculiak. “In these regions and sectors the increase of the minimum wage causes lay-offs, but what is worse and also less visible is that it prevents creation of new workplaces for long-term unemployed. Thus this prevents them from obtaining work experience and gain needed skills.”

Graduates’ requirements

Graduates of universities demand an average monthly wage of €926 per month on average, as stated by Profesia.sk in June 2015 while the requirements rank between €627 and €1,448. Graduates of faculties of Bratislava-based universities have the highest expectations, topped by graduates of the Faculty of Informatics and Information Technology at the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava (STU). They are followed by graduates of faculties of medicine as well as law and media. Graduates of faculties with a focus on humanities from eastern Slovakia have the lowest expectations.

The average expected wage of job applicants searching for work via the Profesia.sk’s website is €840.

“In terms of expected wages this is always proportional to education,” Profesia.sk wrote in its press release. “Wages expected by university graduates are 13 percent lower than wages of university educated people with some practice.”

Dana Blechová from Blechova Management Consulting perceives many wage requirements to be exaggerated.

“Even though there are graduates who work during their studies, thus their wage requirements are more real, the requirements of a large portion of graduates are unrealistic and exaggerated,” Blechová told The Slovak Spectator. “They mostly lack work experience and sometimes also self-reflection.”

Men still earn more

Slovak women earn 19.8 percent less than men on average, a statistic that is worse than the 16.4 percent European Union average, based on Eurostat data from 2013. Estonia has the EU’s biggest gap of 29.9 percent. Among neighbouring countries, Austria and the Czech Republic are worse than Slovakia with 23 and 22.1 percent, respectively. Hungarian women earn 18.4 percent less. The greatest equality was reported in Slovenia (3.2 percent), Malta (5.1 percent) and Poland (6.4 percent).

Profesia.sk confirms this statistics for Slovakia, of women earning 22 percent less. The gender pay gap changes from region to region, while it is the biggest, 24 percent or €240 per month, in the Košice Region. On the other hand the Prešov Region reports the smallest wage gap of €165 per month. In the Bratislava Region the gender wage gap is 21 percent or €294 per month, with men earning €1,413 gross per month and women €1,119.

Blechová sees two reasons behind the gender wage gap in Slovakia: most women interrupt their careers to take maternal and parental leaves and women also show lower interest in managerial positions that are demanding of time and not always favourable to creating the necessary work and life balance.

Luboš Sirota, CEO and general director of McROY Group, sees the gender pay gap a result of the historical development and traditional division of work in Slovakia.

“We remain a rather conservative country in regard to the status of women,” Sirota told The Slovak Spectator. “Our labour market belongs among the most gender-segregated in the EU, which means that women work significantly more often in lower positions compared to men.”

Author: Patrícia Šimák, PwC HRC manager

(source: SME)

(source: SME)

(source: SME)

(source: SME)