Slovakia – once a model of post-communist convergence – is losing ground. After two decades of narrowing the gap in living standards with western Europe, the country is now falling behind – and a lack of investment is both a symptom and a cause of this reversal.

In his commentary, economist Michal Horváth of Slovakia’s central bank warns that “Slovakia has, in recent years, stopped catching up with the living standards of developed Western European countries.” He argues that the country invests too little, and that this is not only a cause of stagnation, but also a reflection of deeper systemic problems.

Slovak businesses point to a familiar list of concerns: labour shortages, volatile energy prices, an uncertain future, and an increasingly unattractive business environment. While such problems exist elsewhere in Europe, Slovakia is seeing significantly fewer modern investment projects – even compared with its neighbours.

“It’s clear that, from the investor’s point of view, the grass is greener beyond our borders,” Horváth writes. “More generous subsidies won’t fix that.”

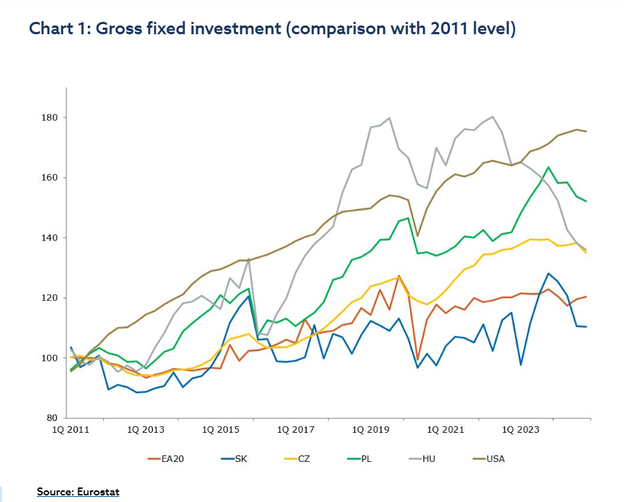

Data from Eurostat show that investment across the eurozone is already trailing far behind the United States. But Slovakia’s position is especially weak. As one of the less-developed EU economies, it should still offer opportunities for relatively high returns – but the evidence suggests otherwise.

Even within the Visegrád Group – Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia – the country is underperforming. “More investment is happening even in our V4 neighbours,” Horváth notes, pointing out that Hungary has attracted more capital despite facing EU funding freezes since 2022. Slovakia’s investment numbers improve only during short bursts when it scrambles to use up EU funds before they expire. “Afterwards, we return to a lukewarm pace of investment growth.”

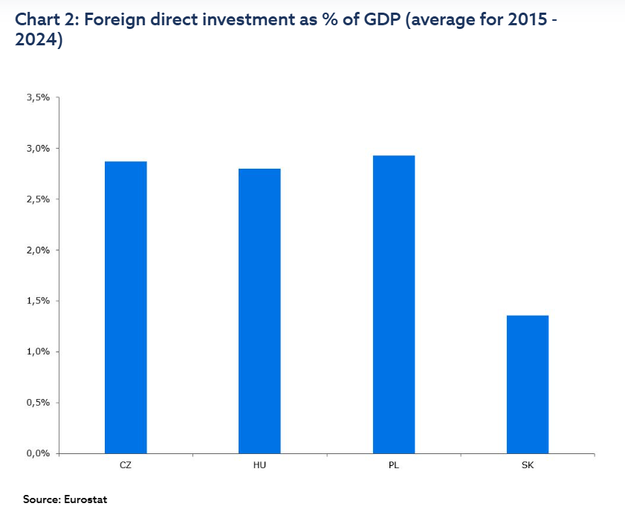

Structural weaknesses are also apparent in private capital. Slovakia lags far behind its neighbours in foreign direct investment. Over the past decade, inward FDI has been roughly half that of the regional average. And the bulk of it comes from firms already established in the country – companies reinvesting profits not in expansion, but in replacing worn-out equipment or cutting costs, including reducing their workforce.

“Larger production expansions, like those we saw last year in some car plants, are becoming increasingly rare,” Horváth writes. “And greenfield investments – like the arrival of a new carmaker in eastern Slovakia – are unfortunately exceptional.”

Public incentives have not reversed the trend. Slovakia offers tax breaks and subsidies to attract foreign investors – usually around €100 million annually across 10 to 20 projects. The aim is to support jobs in poorer regions and attract more sophisticated investment. “In recent years we’ve had more success,” Horváth says, “but the price per job created has risen sharply – over €60,000, compared to about half that in the past.”

Research and development tax incentives have helped slightly, encouraging firms to spend more in this area. But overall, Slovakia remains one of the EU’s weakest performers on R&D – and has already been overtaken by China. “For Slovakia’s future living standards – and Europe’s more broadly – this is an area where improvement will be crucial.”

Why are firms not investing? Surveys by the European Investment Bank suggest several factors: a lack of skilled workers, high and unpredictable energy prices, and broader uncertainty about the future. In Slovakia, these global trends are compounded by an unclear plan for public finances and energy pricing, and increasingly burdensome regulations. “There are likely more obstacles to investment and business here than elsewhere,” Horváth concludes, “and they run deeper.”

Investment statistics, he notes, are unambiguous. “The grass looks greener to investors in our neighbouring countries.” But surface-level fixes – like more subsidies – won’t be enough. The only way to win back investment is to tackle the roots: a predictable business environment, smart public policy, and a better-skilled workforce.

Central bank’s economic outlook – summer 2025

The National Bank of Slovakia has revised its economic outlook downwards amid intensifying global uncertainty and weak domestic growth. The economy is now expected to grow by just 1.2 percent in 2025 – half the pace previously forecast. This slowdown reflects a mix of worsening global trade tensions, weak competitiveness among European producers, and the impact of ongoing fiscal consolidation at home.

Labour market resilience is weakening, with job losses already visible in the private sector and further decline expected. In the private sector, 16,000 jobs are expected to be lost over the next three years. Despite this, wages are set to grow by around 4.5 percent, outpacing inflation, due to labour shortages and agreed public sector pay increases.

Inflation is forecast to average 4 percent this year, but could fall closer to 2 percent in the coming years – assuming global trade disputes ease and energy prices remain subdued. However, renewed geopolitical tensions, such as the recent conflict in Iran, could reverse these trends.

The bank warns that risks remain high and the actual trajectory may diverge significantly from the baseline. In the event of a full-blown global trade war, Slovakia’s economy could shrink by an additional 2 percent by 2027, with 20,000 more job losses.

Given limited fiscal space, government support for growth will hinge on effective use of EU funds and creating a predictable economic environment. Continued fiscal discipline will be essential, with deficits otherwise remaining near unsustainable levels.

Source: NBS

Valaliky Industrial Park, eastern Slovakia (source: TASR - František Iván)

Valaliky Industrial Park, eastern Slovakia (source: TASR - František Iván)