As anyone who has ever attempted to speak a foreign language knows, even after you have mastered the basics, the little things are still going to get you. I have learned this the hard way, as has each and every Slovak who has patiently endured my well-intentioned mutilation of his or her language.

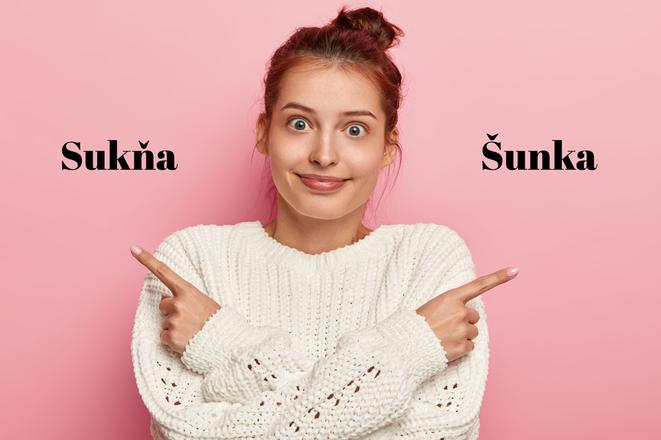

I wasted no time getting started making a fool of myself. In the midst of my first perplexing week in Slovakia I informed my host mother, "I eat chicken, but I don't eat ham." At least, that is what I thought I said, but from the look on her face it was clear that either not eating ham in this country is an idiosyncrasy worthy of a mental exam or I had chosen the wrong word. What I had in fact said to her was, "I eat chicken, but I don't eat skirts," the differences between the words for ham (šunka) and skirt (sukňa) so slight as to be nearly indiscernible to my American ears.

(source: wayhomestudio on freepiks.com)

(source: wayhomestudio on freepiks.com)