Karen Chorba has enjoyed exploring her Slovak and Rusyn ancestry lines throughout her life. Married to a wonderful husband who also has significant Slovak heritage, Karen has found great satisfaction in keeping the holiday traditions and foods, and in passing those things down to her three children. As with her ancestors, spirituality is very important to Karen. Working for nearly a quarter century in the healthcare field as a licensed massage therapist, Karen enjoys helping people to rehab their injuries and to provide them with relief from pain.

Her story is part of a Global Slovakia Project- Slovak Settlers, authored by Zuzana Palovic and Gabriela Bereghazyova. The book is available for purchase via info.globalslovakia@gmail.com.

I grew up the eldest daughter of an immigrant. My father Bill (Vasil in birth records) was only four years old when he, his mother, and sister arrived on the shores of America. His father had come to America a couple of years earlier and had earned enough money to send for them.

Vasil was born in 1926 in the Rusyn village of Čirč, Czechoslovakia, which is now present-day Slovakia. He was the firstborn son to a family that reflected the struggles and challenges of the times.

In those early turn-of-the-century years, only a third of the population in rural, eastern Czechoslovakia had enough land to support their survival. Most were peasants toiling for wealthy landowners with nothing of their own. My grandfather, Vaszul, was one of those peasants. He was not fortunate enough to own any land. So he labored as a lowly field hand while my grandmother, Mária, used every inch of soil around their small home, shared with other family members, to plant enough crops to feed her ever growing family throughout the year.

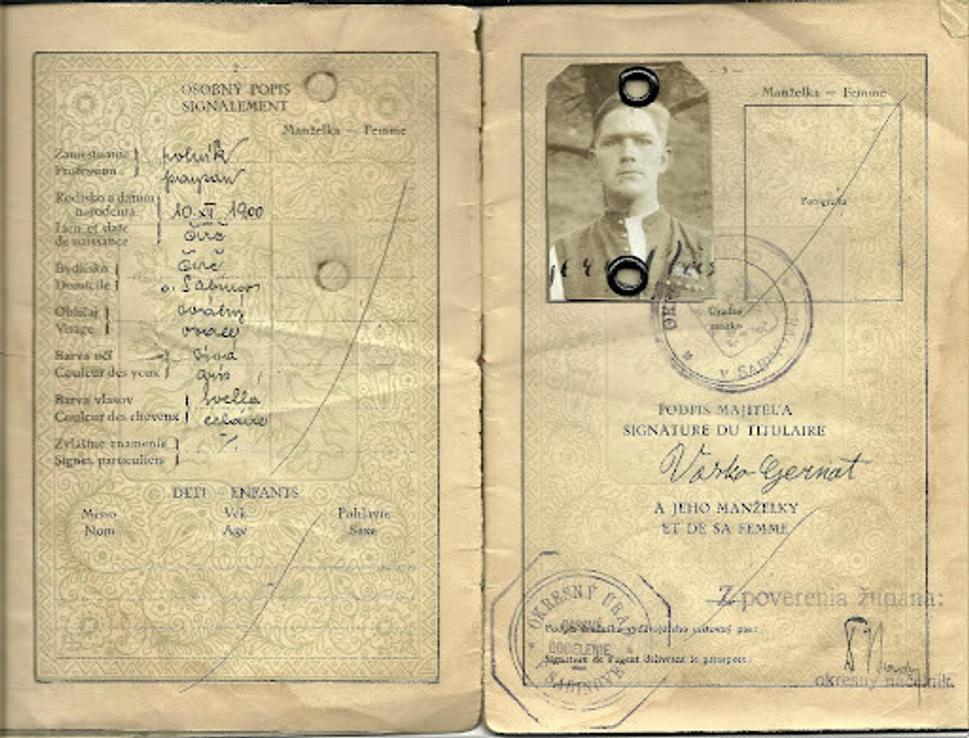

Looking ahead at the prospect of a bleak future in Slovakia, my grandfather was determined to make a better life for himself and his family. The wheels were set in motion in 1927 when Vaszul contacted his brother and a cousin living in Pennsylvania, hoping they would vouch for his immigration application. But, emigrating to America would not be as easy as it used to be, especially after the U.S. Congress began halting immigration from that part of Europe from 1923 onwards.

With few other choices available to him in his homeland, Vaszul decided to persevere with his American dream despite the immigration obstacles. He took it one step at a time, painstakingly filling out all the required forms while diligently jumping through every bureaucratic hoop that lay ahead. Luckily, his paperwork made it through.

Maybe it was meant to be…

When Vaszul boarded a ship anchored in the port at Le Havre, France, in September 1927, his heart was filled with hope. Eight days later, the ship docked in New York Harbor, and Vaszul, soon to become Bill, was excited to begin his new life in America!

Once released by the immigration office, Bill headed to the eastern Pennsylvania coal mines in Windber. I can only imagine the drastic difference in lifestyle. My grandfather went from laboring in the fields, planting and harvesting crops outside in the fresh air and hot sun, to climbing into the cage of a mine shaft which plunged him into a cold black hole deep under the earth. There he would spend the rest of the day in a small tunnel, hammering relentlessly at its walls to break away chunks of coal.

Coal mining was backbreaking work. No one got rich working the mines except for the mine owners who profited off the backs of their immigrant employees. Money was scarce as Bill was forced to work diminished hours because the mines had to cut back on labor. At the same time, he was paying rent to his cousin and repaying the ship passage loan he had received from his brother. But he also needed funds to send back home to support his wife and children. In his effort to save money for his family, Bill sometimes survived by eating only bread and bananas. He scrimped and pinched pennies as much as he could in order to be able to accumulate enough money to bring his wife and children to this new land. How much he missed them!

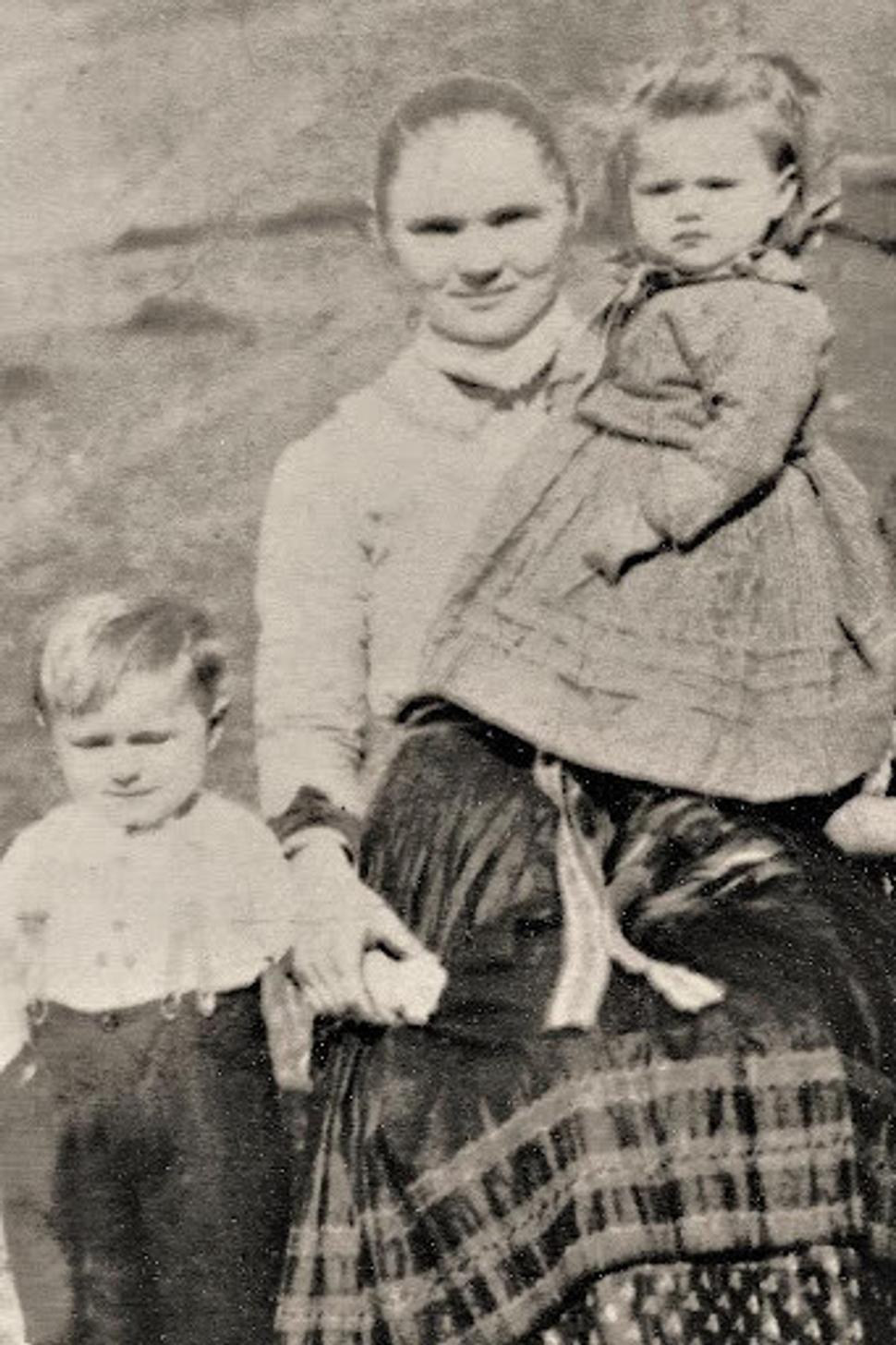

Meanwhile, back in Čirč, Bill's wife Mária patiently waited. She had been five months pregnant with their second child when her husband left for the U.S. Their baby girl was born while Bill was far away. With her husband living across the ocean and a young son and an infant daughter to care for, Mária's family helped out as much as they could.

Finally, the long-awaited day came. The American Consulate in Prague issued the documents to permit Mária and the children to join her husband who had financed their ship and train passage. Mária packed up her few belongings to prepare for the long journey to America. On departure day, her family gathered together at the train station in Čirč to say their tearful farewells. They knew all too well they might never see each other again. But to Mária, the saddest parting of all was having to leave behind her four-year-old sister, Margita, who was only six weeks older than Mária’s own little boy. Her heart was heavy, as she knew that everything would soon be different: family, landscapes, lifestyle, and customs.

While crossing the ocean, Mária had a violent bout of seasickness and was not able to keep the children at her side. Some passengers were upset because her carefree, rambunctious four-year-old son and his two-year-old sister were running up and down and playing all over the ship’s deck. But for Mária, the vision of soon seeing her husband again made it all worthwhile. After two weeks at sea followed by a long train ride, the little group disembarked in Windber. Finally, the family was reunited!

Bill and Mária (Mary) were delighted to be together again after two and a half years apart. This was the first time Bill saw his daughter, and his son had grown so much in his absence! A year later, the couple joyously celebrated the addition of another daughter to their family. With high hopes, the family of five, now complete with their new American baby, was ready to begin writing their next chapter.

But life in a mining town was rough—and dirty, and sweaty, and smelly, and exhausting. Everything in sight was covered with coal dust. It permeated every aspect of a family’s existence. The coal’s black soot filled the air, blanketing sidewalks, and porches, and railings. It insidiously found its way inside their homes, dirtying clothing, furniture, bedding, and rugs. Floors needed to be scrubbed, not just washed, to get rid of the filth. Bedding was boiled to get out its stains. Even the air stunk. The hydrogen sulfide gasses released in the mining process seeped into the air, making it smell like rotten eggs.

When Bill came home from work he was blackened from head to foot in coal dust except for the whites of his eyes. Mary would draw water, heat it up on the coal and wood stove, and pour it into a portable tub placed in their kitchen so that her husband could clean up after a long, exhausting day in the mine. There were no bathrooms, just outhouses, always shared with neighbors, and therefore especially inconvenient for a family with children.

To bring in some much-needed extra money, Mary did cleaning-work and even some wallpapering for the wealthier people in town. As the children grew, they too contributed by doing various chores for neighbors in the hope of trading their labor for some milk or even a small bit of a cow or pig that had been butchered. It was a daily struggle, but by pulling together, the family survived.

By 1944 my grandfather had worked 18 years in the mines. He’d had his fill of living in the dark, and he was done with rarely seeing daylight and barely making a living. By then, he had accomplished what he had come to America for—his children surpassed anything that was ever available to him in the home country. Although still in school, his girls were well on their way to becoming educated American women, and his son had obtained a high school diploma without ever having to work even one day in the mines like many other children did. It was time for a change.

Bill’s decision was final. The family would move, leaving the coal mines far behind.

Bill found work at a local brewery in Cleveland, Ohio, where he cleaned huge vats and tanks that held beer which was in the fermenting process. Instead of spending his work shift getting filthier as the hours passed, Bill’s job was now just the opposite: he was wet and clean all day. Although he never had a high-skills job, my grandfather always tried to take good care of his wife and children.

However, the family arrived in Cleveland incomplete. Bill Jr. had finished his high school studies a couple of months early, enlisted in the Navy and left to fight in WW2. It was Bill’s mother who proudly accepted his diploma on the high school stage.

With their only son off to join the Allies, my grandfather was distraught. He knew the atrocities of war all too well. As a teenager back in Slovakia, he had been conscripted and fought in the previous world war. He raged when he first found out that his wife had signed the papers for their son to join the Navy. But nothing could dissuade my father. He had come to the United States as a young immigrant boy, but he was now an American, and he was determined to fight for his country.

Bill’s ship, the USS Tabberer, was assigned to the Pacific Theater. He was the ship’s cook, but during battles, he manned the guns like the rest of his shipmates. In combat, the young eighteen-year-old sailor, so far away from home, watched in horror as his friends on either side of him were pierced with bullets sputtering from the Japanese Kamikaze planes. In fact, Bill’s own life nearly came to an abrupt end during a fierce storm of cataclysmic proportions.

Typhoon Cobra, also known as Halsey’s Typhoon, ripped through the Pacific, sunk ships, and caused so much damage that it was the first cyclone ever given a name. The sea was rough, with waves up to ninety feet high and wind gusts up to 185 miles per hour. The salt in the seawater, whipped by the wind’s fierceness, ripped into the sailors’ faces, cutting like splinters of glass. Torrential rains and winds washed men, screaming for life, overboard. The storm raged for 24 hours. My father’s ship was severely damaged and left with no radio capability. Despite that, the next day the ship began to methodically circle the area, rescuing men from the freezing ocean water. In total, 55 men, all from capsized destroyers, were plucked from the brink of death, warmed, attended to in sickbay, and fed with the ship’s best food, prepared by my father. Typhoon Cobra’s destruction was immense, and it is still recorded as the worst natural disaster in U.S. Naval history.

The war would not leave my father unscathed. When he returned home, he suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In those days it was called “battle fatigue” or “combat disorder.” But after his naval discharge, Bill met a pretty Slovak girl at a roller-skating rink who would help him heal his invisible wounds.

She was the girl of his dreams and the two fell head over heels in love. Agreeing to adopt her Lutheran faith to win her hand, Bill and Dorothy married. But torturous wartime nightmares still haunted him. Awakening suddenly in the middle of the night, Bill would leap up and hide on the side of the bed. These episodes were terrifying for my mother. Eventually, Bill managed to move on and establish a relatively balanced life with his wife and four children, although the scars from his past would remain. Through the ups and downs of life, Bill and Dorothy remained sweethearts until the end of their days.

As for my grandparents, they were so relieved when their only son returned home from the war alive and in one piece! But the challenges of normal everyday life persisted. The move to Ohio certainly had not meant they could leave hard work behind. Although their new home in Cleveland was in a more urban area, their financial situation was no different. The family needed every penny.

Mary certainly wasn’t a stranger to hard work, and over the years she spent many of her evenings at different cleaning jobs. With time and determination, my grandparents were able to save enough money to purchase a car and to put a down payment on a house of their own. Their home was a cute little place with a sunny yellow kitchen and beautiful roses growing in the yard. And my grandma’s carefully planted garden provided an abundance of vegetables which she canned for use in the winter. A mixture of modern America and old world Slovakia, their home reflected them perfectly. There was an enormous weaving loom in the basement on which my grandmother made multicolored rag rugs that she was able to sell for a little extra income. Scattered around the house were doilies and other crocheted items, handmade by my grandma’s sisters in Slovakia, and a treadle sewing machine that captured my heart. Years later, I inherited her sewing machine, and I used it several times when making clothing for my own daughters.

God was very important to Bill and Mary. Prominently displayed in their dining room was a Sacred Heart of Jesus picture, while the Immaculate Heart of Mary hung high on the wall of their bedroom, and a depiction of the Last Supper presided over their kitchen table. Over the years they had changed from their original Greek Catholicism to Orthodoxy, attending a local Russian Orthodox Church. At one point, my grandfather got into a huge argument with his Byzantine Catholic brother in Pennsylvania over their chosen religions. The brothers did not speak to each other for fifteen years because they were both so bullheaded.

Practicing Eastern Christianity also meant that our Easter and Christmas observances were doubled. During those celebrations, their house would be filled with delightful ethnic fragrances which would hit my nose as soon as I walked through the door. At Christmas, the aroma of mushroom soup and holúbky wafted in the air, making all of us eager to eat. Bowls of huspenina/kočenina (aspic made from pork legs) were lined up on the steps of the very chilly stairway leading up to their attic, due to my grandmother’s limited refrigerator space. Bobálky, apricot and prune koláče, along with nut and poppy seed rolls were on the festive menu too.

My grandma made everything the old-fashioned way: a handful of this, a pinch of that. Eventually, my uncle wanted to have a more precise nut roll recipe. So, as he watched his mother-in-law baking, he measured and wrote everything down. This treasured recipe is still in the family, recreated each year. Unfortunately, the rest of my grandma’s recipes are lost to the past. How I wish I could travel back in time and spend just one day with her in her bright, sunny kitchen, learning all her special recipes!

Looking back on all the great remembrances I have of my grandparents, the ones I cherish the most are my memories of the endearing features of their personalities. The warmth of my grandma’s huge, strong, enveloping hugs when we walked through the door, her hearty laugh, and her slightly broken English are all precious recollections. When upset or frustrated, grandma would sigh and drop her head and move it back and forth in a “no” type movement and say in her singsong tone: “Bože môj. Bože, Bože môj!” Other times, for emphasis, she would add a thump of her closed fist on her chest.

With her childhood shaped by rural eastern Slovakia, my grandmother never shook off the superstitions she had learned as a young girl. Dreams and events could quickly bring on a sense of foreboding and worry for her. Growing up so close to nature on the slopes of the Carpathian Mountains, my grandma was also a natural weathervane. Mary could tell when a weather front was coming through and, even when the sun was shining brightly, if my grandmother said it would rain, it was a near certainty that an umbrella would be needed sometime that day!

My grandpa was very strict, but later in life there was an impish, playful sense of humor that occasionally surfaced. There were sit-up competitions with his grandchildren even when he was into his sixties. He would tease his young granddaughters, asking them if they had a boyfriend yet. When I was about ten years old, he would come up beside me, dance a little jig, and say in his broken English: “you gonna get married soon? I dance at you wedding!” And we would laugh.

Unfortunately, by the time I did get married my grandpa’s legs had been amputated due to arteriosclerosis. First one, then the other. He was embarrassed to attend my wedding in his condition, which broke my heart. I arranged for the bridal party to visit him at home, so that I could have pictures with my grandpa on my wedding day, even though he wasn’t able to dance with me. And I’m so glad that I did. Tragically, my grandpa passed away just a few days later.

Over the years there were many twists and turns as I traveled along the road to discovering my ethnic identity.

My grandfather fully embraced being Slovak. It was my father who came upon information suggesting the possibility of Carpatho-Rusyn roots. In the early 1960s, he and my grandfather would argue back and forth. “We are Slovak!”, my grandfather would yell. Emphatically my father would bellow back, “We are Rusyn!” And on it went until one of them gave up. I can still recall my grandfather ending a session with a disgusted, dismissive wave of his hand. I do not know why my grandfather insisted on being Slovak. He came from a Rusyn village, the language his family spoke was slightly different from Slovak, and everyone was baptized in the Greek Catholic rite, a hallmark for the Carpatho- Rusyns. All evidence pointed to my father being right. And my dad emphatically insisted he was “Carpatho-Rus” (as he called it) until the day he died.

I, on the other hand, knew nothing about Rusyns. In fact, I thought the word my father was saying was ‘Russian’, not ‘Rusyn’. As a young girl living through the tense years of the Cold War, the thought of going to school and having anyone find out I was part Russian was the most horrible thing I could imagine! So, I dismissed my father’s rantings.

Yet, those arguments between my father and my grandfather nagged at me, playing over and over in my thoughts. As time went on, the internet brought to light a staggering amount of new information about Carpatho-Rusyns. I was happy to dig in and gather evidence. Yet, in the end, the answer had been staring me in the face all long: my father’s birth name. Vasil is a distinctly Carpatho-Rusyn name. Furthermore, it was officially recorded in church records in Cyrillic. So, now, many years after those arguments between my father and my grandfather, here I stand, united in solidarity with my father. And just like him, I can now truly declare: “I am (at least in part) Carpatho-Rusyn!”

After my grandmother and my father passed away, there was no contact between my family and the relatives in Slovakia. When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, it was an invitation to the world to restore family bonds. How happy my father would have been to witness that! Sadly, he passed away a year before the Velvet Revolution.

My husband and I journeyed to Slovakia in 2016 to see the ancestral places where both our families originated. What a blessing it was to walk on the land where my father, grandparents, great-grandparents, and so many generations before them had been born! With my bare feet, I dug my toes into the dirt and felt the connection to my ancestors. It was a feeling that energized me. The air was fresh and the beauty of the countryside in eastern Slovakia was incredible! Right then and there, I fell in love with my ancestral country.

Prior to our trip I knew almost nothing about my relatives in Slovakia. Yet we received a genuine and heartfelt welcome. They were happy that their land and heritage were still important to us. With open arms, our Slovak family presented us with the ritual of salt, bread, and slivovica. Our hosts were the children of my grandmother’s youngest sister Margita, who as a little girl many years before, ran and played with my father before he left for America. We had come full circle. And once again, after 86 years, our family was reunited.

During our visit, I had a conversation with my family, and I asked if they considered themselves to be Slovak or Rusyn. I expected them to tell me they were Rusyn, but I was wrong. Growing up in Slovakia, they considered themselves to be Slovak. So, once again, the question came around, teasing me: Am I Slovak, or am I Rusyn? But this time I know the answer, and I’m confident in my Rusyn roots.

A year after our trip to Slovakia, four of our newfound family members visited us in the U.S. They surprised me with a lovely, handmade kroj, fashioned after the folk costumes worn by my grandmother when she was a young woman living in Čirč. It brought tears to my eyes. I was amazed by the beautiful colors, fabrics, and textures. It fit perfectly and even though it was an outfit fashioned after those worn by peasants, I felt like a princess when I was wearing it! But what meant the most to me was the thoughtfulness of my family in bringing a part of my historical culture to me and accepting me as one of their own. It is a gift I will treasure as long as I live.

Kočenina (huspenina)

(8 servings)

4 pigs’ feet, split lengthwise

½ head garlic, cloves separated and peeled

1 tbsp salt

1 tsp pepper

2 tbsp sweet paprika

1 large onion, peeled and quartered

1) Rinse off the pigs’ feet and place them in a big pot, adding enough water to cover.

2) Bring the water to a boil, turn down the heat, and simmer slowly. Skim the surface of the water until there’s no more foam.

3) Add the garlic, salt, pepper, paprika, and onion.

4) Simmer 3-4 hours, until very tender and the meat almost falls away from the bones. The liquid should taste like a nice, rich soup broth. If it’s a little bland, add more seasoning, to taste.

5) When cool, remove the pigs’ feet from the pot and place them in pretty bowls or refrigerator storage bowls with lids.

6) Ladle the broth directly into the bowls, through a strainer. Cover the bowls with plastic wrap or lids, then refrigerate them overnight. The broth will turn into a gel (aspic).

7) Serve chilled, with rye bread.

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)

(source: Karen Chorba)