There are several things that come to mind when pondering the similarities between the Irish and the Slovaks: their down-to-earth nature, lively folklore, and fondness for potatoes. But beyond these surface-level traits lies a deeper, more poignant connection — their shared histories of emigration.

Slovaks were the second-largest emigrant nation in Europe during the great waves of migration to America, surpassed only by the Irish. This is no coincidence, but rather a reflection of parallel historical circumstances that drove both peoples from their homelands.

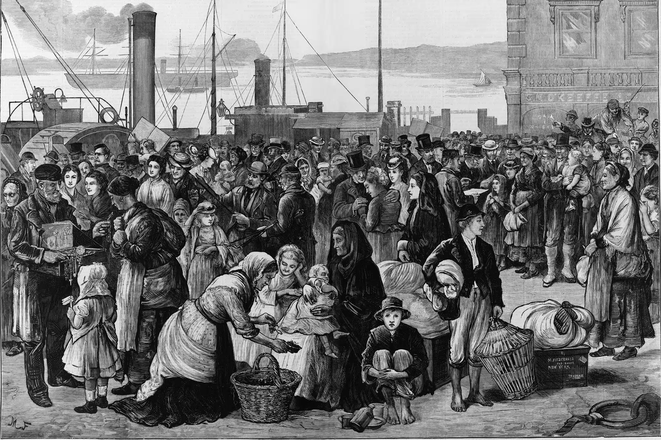

The Irish were among the first Europeans to seek opportunity at the bottom of the social hierarchy and career ladder in industrial America. Only after they began to resist the inhumane conditions and meagre wages in mines and steel mills did industrialists turn their attention to Slavic Europe. Slovak immigration peaked between 1880 and 1914, when approximately 650,000 Slovaks — about one-third of the nation — left for America. Like the Irish before them, they were compelled by economic necessity, but also inspired by the hope of a better life.

Neither the Irish nor the Slovaks found it easy to leave behind their land, families, and the myths and legends of their homelands. Yet they had little choice. Emigration was both an act of desperation and an expression of hope.

For both peoples, America represented not just an escape from poverty, but from political oppression. The Irish fled British colonial rule; for Slovaks, emigration offered relief from harsh Magyarization policies. In both cases, they were leaving societies in which their cultural identities were under threat from dominant powers.

The experience of emigration left indelible marks on their cultures. In Irish literature and music, the theme of exile is ever-present. Slovak cultural expression, too, reflects this sense of displacement and longing for home — evident in folk songs that speak of separation and the sorrow of leaving loved ones behind.

Perhaps most remarkably, the diaspora communities of both nations played crucial roles in their homelands’ struggles for independence. Irish-American support was instrumental in funding the Irish independence movement. Similarly, Slovak-Americans were vital advocates for Czechoslovak sovereignty, with the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Agreements — both signed in the United States, not in Europe — laying the groundwork for an independent Czechoslovakia.

While the stereotypical associations — hearty peasant cultures with rich folklore, musical traditions, and yes, a culinary affinity for potatoes — contain some truth, the deeper parallels between Irish and Slovak experiences offer far more profound insights. Both nations endured centuries of domination by larger powers. Both preserved language and culture as acts of resistance. And both continue to navigate the complexities of being small European nations with large diaspora populations.

As Europe continues to evolve, these two nations — one on its western edge, the other at its centre — can be more than historical parallels.

Slovakia is only beginning to develop strategies for engaging its global diaspora and harnessing its potential for economic and cultural enrichment. What better teacher could there be than Ireland?

The Irish have transformed their diaspora connections into diplomatic, economic, and cultural assets. Will the Slovaks follow their lead?