THE EYES of the entire sporting world are on Beijing, where the Summer Olympics are taking place. Slovakia is no exception, having sent a delegation of 57 athletes to bring home as many medals as possible.The Olympic hosts have used the increased interest as an opportunity to organise events introducing and promoting their country worldwide.

The Experience China in Central Europe – Slovakia project is part of a series of events that are being organised across the region.

An exhibition entitled World Heritage Sights in China, which is part of the project, opened in the Slovak National Museum (SNM) in Bratislava on July 2.

“More than 3,500 people viewed the exhibition during its run until August 3,” Jana Chrappová, a spokesperson for the museum, told The Slovak Spectator. “The museum considers the exhibition, which took place during the summer holiday, to have been very successful. The guest book had comments by tourists from France, Germany and China.”

The project continues with documentaries on Slovak Television exploring Chinese culture through traditional medicine, tea, cuisine, and martial arts such as kung fu.

Since the cooperation between China and Slovakia is mutual, Slovak artists are also bringing the culture of Europe to Asia.

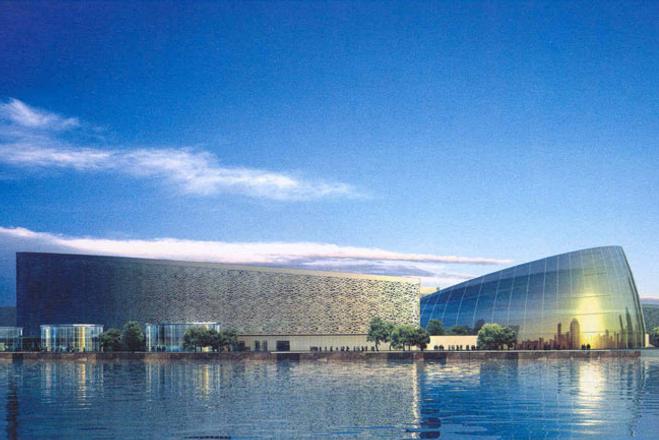

The ballet troupe of the Slovak National Theatre (SND) was the first ballet ensemble to perform in the new Sciences and Cultural Arts Centre in Suzhou, which is in the Jiangsu province, about 100 kilometres west of Shanghai.

The 35-member troupe performed Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker between December 23 and 25 last year.

“More than 3,000 people came to the performances,” Zuzana Golianová, the spokesperson of the Slovak National Theatre, told The Slovak Spectator.

Chinese pupils from the local ballet school rehearsed for weeks to perform the children’s roles in the show.

Slovakia can be also proud of Marina Čarnogurská, who was honoured in 2003 for her translation of Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber, one of the most important works of classic Chinese literature.

On the 240th anniversary of Cao’s death, China evaluated the translations of this masterpiece, and selected Čarnogurská’s as the most faithful and elegant in the world.

The Sme daily reported that Čarnogurská began translating the four-volume tome in the 1970s, after her publications were banned by the communist regime in the former Czechoslovakia.

She kept her knowledge of Chinese linguistics fresh by translating about two pages every day, without respect to whether her work would ever be published.

After the fall of communism, all four volumes of the translation were published, and Čarnogurská garnered wide acclaim.

The SND Ballet performed in the Sciences and Cultural Arts Centre in Suzhou. (source: Courtesy of SND)

The SND Ballet performed in the Sciences and Cultural Arts Centre in Suzhou. (source: Courtesy of SND)