SLOVAKIA will mark the 19th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, which signalled the end of communism in Czechoslovakia, in two ways. It will contemplate to what extent parliamentary democracy has taken root since that fateful day, and it will celebrate the cancellation of the visa requirement for Slovak and Czech citizens travelling to the United States.

Fedor Gál, the co-founder of the Public Against Violence (VPN), which was the Slovak counterpart to Václav Havel’s Civic Forum, recalled for The Slovak Spectator that there were signs the communist regime was crumbling well before November 1989.

“The bloody regime simply exhausted its ability to lie, manipulate, threaten … and compete economically and militarily with the democratic West and capitalism,” Gál said. “The Czechoslovak story is historically connected to the student revolt in Wenceslas Square [in Prague].”

Some people, such as Ján Slota, chairman of the Slovak National Party (SNS), have suggested that the dissidents and demonstrations had little effect on the regime.

“Let’s stop pretending: [the communist secret police] orchestrated the Velvet Revolution,” Slota said on the public Slovak Radio (SRo) station last May. “Only a naive fool would believe that some dissidents caused it.”

But Milan Žitný, who co-chaired the November 17th Commission after the revolution, completely rejects Slota's theory.

“The events definitely occurred spontaneously,” he told The Slovak Spectator. “There’s no chance that the ŠtB [communist-era secret police] was involved.”

Yet even Prime Minister Robert Fico has in the past downplayed the revolution’s importance.

“I got a job that year, and I worked,” he told the Domino Fórum weekly in 2000, while an opposition politician. “Looking back on it, 1989 was not a milestone in my life.”

Fico has never retracted this statement.

Mária Hlucháňová, a journalist who worked at the SRo during the revolution, strongly condemns it. She expressed her concern to The Slovak Spectator that today’s young people are unaware of and uninterested in the lessons of November 1989.

“I’m concerned about whether this date will be commemorated at all three of four years from now,” she said.

She added that distorting, or even forgetting, such an important date in the country’s history diminishes the value of democracy. This leaves open the chance for the totalitarian regime to be repeated, she said.

How it unfolded

Gál’s memories of the Velvet Revolution are vivid.

“There were meetings, public discussions, prison riots, changing of the guard from bottom to top, the creation of a standard political agenda, preparations for the first free election, and many other things,” he recalled. “All of this was accompanied by euphoria, stress, fatigue… and the feeling that we were part of history.”

Žitný pointed out that, though November 17 is considered the beginning of the Velvet Revolution, there was no sign of it in Bratislava that day.

He was working as a writer and dramatic adviser on a student theatre production at the College of Music and Dramatic Arts (VŠMU), he explained, when one of his students asked to meet him at the famous Piváreň Umelecká Beseda.

Dozens of people had already gathered there by the time he arrived. He heard the actor Milan Kňažko announce that police in Prague had disrupted a student demonstration on Wenceslas Square, leaving several injured.

Žitný explained: “A protest petition was immediately drawn up, which was the true beginning of the Velvet Revolution in Bratislava. Actors stopped performing, choosing instead to read the petition and start political discussions. VŠMU became their first base, where they formed the VPN. Later, meetings began on SNP Square, where Kňažko, Gál, Ján Budaj and others held speeches. Others then joined them.

“I remember several funny stories, too. Once, a man came to the VPN holding a plastic bag full of Czechoslovak crowns, which he claimed was a donation from the ‘veksláci,’ the illegal money-changers who worked on the streets of 1980s Czechoslovakia .

“At the beginning of December, talks were held at the Slovak National Theatre, in which Václav Havel, who would later become president, took part. The result was the abolition of the Article 4 of the Constitution, which banned any political grouping other than the Communist Party. This was a crucial achievement, along with the abdication of the communist government. Others were the dissolution of the ŠtB in February 1990 and the free elections that took place in the summer of 1990.”

Gál added, “While it was happening, the situation changed from one minute to the other. Twists and turns became the norm. But, from the very beginning, we resolved to do two things: abolish the leading role of the communist party and organise free elections.”

The Commission is formed

In November 1991, Czechoslovakia’s Federal Parliament passed the Lustration Act, which banned anyone who had served in the ŠtB or collaborated with it from being given government or certain public sector positions.

“The reason was that they should face the consequences for their previous activities,” Žitný explained.

He noted that the ŠtB recruited informants to pass along information on family members, colleagues and neighbours. Some people collaborated voluntarily, but others were forced into it, usually under threat of imprisonment for their own transgressions. This latter group of people were called “candidates” or “ŠtB confidants”.

As a result parliament founded the November 17th Commission, an independent body tasked with evaluating whether a person had collaborated with the ŠtB voluntary. Žitný was its vice-chairman.

“The members of the commission studied each person’s file, heard their testimony, and then decided,” he said.

The commission worked on hundreds, possibly thousands, of cases throughout 1992. Žitný eventually came to the conclusion that most people fell into the category of “candidate” or “confidant,” so he requested that they be excluded from the Lustration Act. The Constitutional Court ruled to that effect in November 1992.

Žitný defends the Lustration Act, saying that allowing people associated with the ŠtB to attain public positions would have made it impossible to establish democracy. He said the act’s value is proven by the fact that it is still in force in the Czech Republic.

Stories of resistance

Žitný related the details of some of the cases that came before the commission.

One involved a young college student whom the ŠtB approached at the end of the 1980s. The student performed several tasks that were asked of him. But when he was eventually asked directly, he refused to collaborate.

That night, ŠtB agents attacked the student, Žitný said. Even so, he refused to collaborate, and told the agent who had originally approached him, “You are in your thirties. You are not some dim-witted Bolshevik. Don’t you see that the regime is about to fall? The new regime will need someone as intelligent as you.”

“After the revolution,” Žitný stated, “the student was elected to parliament. He now serves as the secretary for Czech President Václav Klaus. His name is Ladislav Jakl.”

Žitný also spoke of an employee at a TV station in Prague who refused to collaborate with the ŠtB.

After studying her file and hearing her testimony, the Commission decided to recognise her bravery.

“When I told her that we were expressing our deepest praise for her humanity, she was so moved, she started crying,” Žitný said.

Both Žitný and Gál believe that the main objectives of November 1989 – free elections and diversity of political belief – has been achieved. Gál said this is true despite the rise of populism in recent years.

“The Velvet Revolution has not stripped people of responsibility for their deeds,” he said. “Slovaks elected Vladimír Mečiar, Ján Slota and Robert Fico freely.”

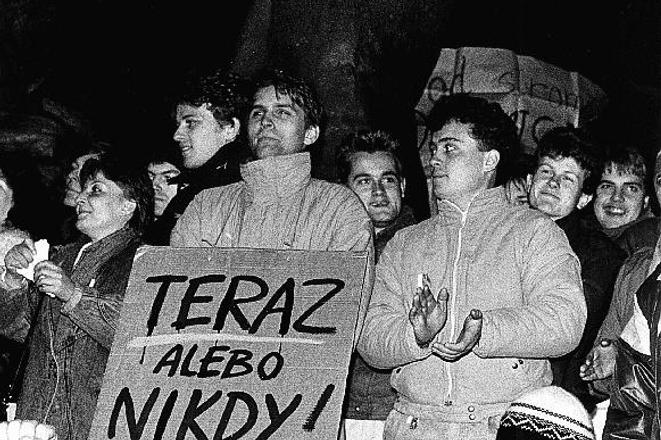

Now or never, says the slogan back in 1989. (source: Ján Lörincz)

Now or never, says the slogan back in 1989. (source: Ján Lörincz)