PEOPLE from countries that already belong to the eurozone often say that some weeks after the switch to the euro they felt like they were living in a foreign country, where one needed to get accustomed to paying with another currency.

For Slovaks, however, a different currency might not be such big deal, despite all the necessary mental arithmetic, the uneven conversion rate and the new banknotes and coins everyone will need to get used to. Because it will be the sixth time since 1919 that Slovaks have experienced a significant change in their currency.

“As a nation, the Slovaks are easy to adapt; we often even hear the question asked whether Slovakia is a laboratory for trying new reforms,” said Marián Tkáč, the head of archives at the National Bank of Slovakia.

The 20th century did not only see several changes to the currency, but also witnessed several significant economic upheavals: land reform, Aryanisation, nationalisation, privatisation, and several regime changes.

“People have always remained people,” Tkáč said, adding that there’s no need to worry about the Slovak adaptation to euro.

Controversial currency reforms of the 20th century

“Each currency change takes place to ‘solve something’,” Tkáč told the Slovak Spectator.

Most of the changes that took place before now were linked to the foundation of a new state and one of them – in 1953 – was connected to the change in the political regime dating from 1948, when communists took power in Czechoslovakia.

According to Tkáč, the most controversial changes in currency in the modern history of Slovakia took place after WWII: the currency reform in 1945 and the so-called money reform in 1953. These were the ones that stirred most negative feelings among Slovaks.

In 1945, when Slovakia reintegrated with the Czech lands, people were sceptical about accepting the new Czechoslovak crown, especially because the Slovak currency of the time was relatively strong, Tkáč explained. Another problem was that the currency reform was accompanied by a system of ration tickets which Slovaks had not previously experienced, even during the war.

“A ration-ticket system means that money is of no use to you unless you also have special tickets. Without them it is impossible to buy goods,” Tkáč said. In Czechoslovakia, this system lasted until 1953 when, he said, the communists “needed to take money away from people” and introduced what they called a money reform in which the currency formally remained but all existing notes and coins had to be exchanged.

Despite the fact that the reform abolished the rationing system, it was followed by tremendous changes in the national economy since people were deprived of the savings they had managed to gather in the post-war years. People could exchange only 300 crowns at a favourable rate of 1:5, the rest were exchanged at a ratio of 1:50. All money had to be exchanged in the course of five days. According to Tkáč, this was the toughest change that Slovaks had to go through.

Slovak crown reintroduced after the break-up

The Slovak crowns that Slovaks will be able to use until January 16 only marked their 15th anniversary this year. The original plans counted on the Czechoslovak federal currency remaining valid for at least six months after the break-up of Czechoslovakia, to give enough time for both countries to prepare their new currencies, the Sme daily wrote.

In the end, the Slovak crown was introduced on 8 February 1993, which was also the day when the agreement about currency union with the Czech Republic came to its end.

“Fifteen years ago there was no reason for nostalgia, the new state was there, and along with it its child, the new currency. After all, the crown was still there, only in another, and dare I say it, not uglier dress,” said Tkáč, who attended the birth of the modern Slovak crown and the establishment of the National Bank of Slovakia in 1993. His proposal to rename the new currency from ‘crown’ to ‘ducat’ (to follow the old tradition of the mint in Kremnica) was refused at the time, and he admits there might have been some nostalgia for the crown if the name were to have been changed then.

Tkáč also said there was no need for a large information campaign as is the case with the euro switch.

“It was enough if my colleagues and I gave a couple of interviews to television or radio and explained to people what was going on,” he said. “No campaign, no calculators, no millions spent on informing the citizens.”

New century, new currency

This time, however, the currency change requires citizens to be well informed, as it is specific in many ways, particularly the conversion rate.

The past currency changes (with the exception of the money exchange in 1953) always operated with a ratio of 1:1; now the conversion rate is Sk30.1260 for €1.

“I myself am afraid of converting the sums, and thus multiply and divide by thirty… and I’m also afraid about where to put all the coins so that they don’t split my pockets,” said Tkáč, who shares these concerns with most Slovaks.

But the switch to the euro is special for Slovaks in a completely different respect too: it’s a currency the Slovaks have had to earn, to work hard for, and in that sense, Tkáč said, they have succeeded over their neighbours: the Czechs, Hungarians and Poles. With the switch to the euro Slovaks are saying goodbye to the crown that was present here in different forms for 106 years; but it is the first time that the currency has been changed due neither to a change in political regime or state, nor to the weakness of the crown.

“On the contrary, the underdog and outsider from 8 February 1993 has become a leader in a historically short time,” said Tkáč. Slovakia was the first in this region to meet the stringent Maastricht criteria. Starting next year, 320 million Europeans will be able to use Slovak euro coins and this will contribute to making Slovakia more visible in European countries.

The switch to the euro is often referred to as completion of the process of ‘the return to Europe’ that Slovakia was torn away from during the cold-war years. According to Tkáč, the January 1, 2009 date might be just another currency reform that people do not remember so well. But it’s possible that the euro will become a symbol of the definitive ‘Europeanisation’ of Slovakia for some time, especially if it helps improve the lives of people in the country.

Will it be so? “By nature, I am an optimist,” Tkáč concluded.

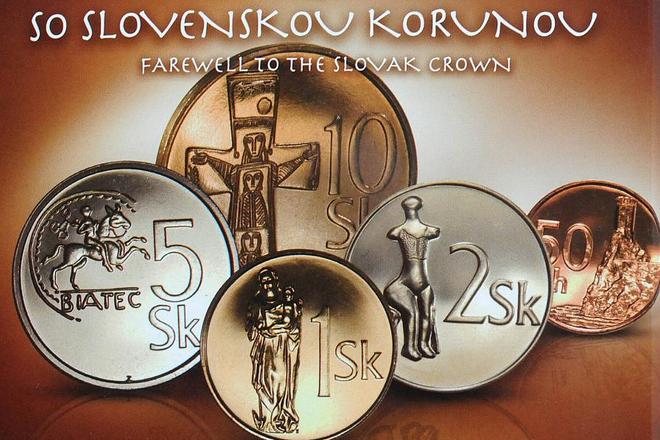

The Kremnica Mint has released a commemorative set of Slovak crowns. (source: TASR)

The Kremnica Mint has released a commemorative set of Slovak crowns. (source: TASR)