FAST and easy solutions, standing up for ‘all decent people’, fighting the ‘mismanaged and corrupt’ system: these are a few of the new slogans currently used by extremists to bring their views into the mainstream. Extremist groups and their opinions are not relegated to the margins of society, the police admit in a recent report, while human rights watchdogs warn of extremist views being adopted by mainstream politicians.

The number of detected crimes related to extremism sharply increased in 2011 to 271 (compared with 115 detected the previous year), according to the Report on Fulfilling the Tasks Based on the Conception of the Fight against Extremism, which was submitted for interdepartmental review on October 11, 2012.

“The increased number of reported cases is connected with the police’s focus on this area,” said Michal Slivka, the spokesperson of the Police Corps Presidium, adding that with hate crimes it is often the case that the victims do not report them because they are intimidated and repeatedly threatened with further violence from the perpetrators.

According to police statistics in 2011, however, only about 45 percent of the detected crimes of extremism were actually investigated. Irena Bihariová from the NGO People Against Racism (LPR) sees several reasons behind this.

“It is the result of long-term trivialisation of this issue,” she said, adding that for years the police have complained that they lack sufficient support from the Interior Ministry, that there is a shortage of staff and that they do not receive professional preparation and training. “This area really requires radical legal, organisational and personnel reform,” she said.

Bihariová does not believe that the reported statistical increase of criminal acts of extremism sheds much light on the current situation.

“If one notices the structure of specific criminal acts that were recorded, it suggests that the police got stuck somewhere in 2004 in identifying this type of criminality,” Bihariová said.

The most frequently detected criminal act is the promotion and support of movements directed at limiting the rights and freedoms of others, which includes swastikas graffitied at bus stops or groups of drunken youngsters giving Nazi salutes.

“While the police make detecting such crimes their showcase for their fight against extremism, in reality they are failing to notice the growing core that has long since ceased presenting itself through Nazi salutes, swastikas and T-shirts with forbidden topics,” Bihariová said.

Abusing frustration

Even though the public shuns extremist groups overall, people tend to agree with some of the specific ideas that extremist groups promote, a research project from 2011 called Public Opinion on Right-Wing Extremism, authored by sociologists Elena Gallová Kriglerová and Jana Kadlečíková from the Centre for the Research of Ethnicity and Culture, supported by the Open Society Foundation, has shown.

“It seems that their current activities are an attempt to change their negative image,” Gallová Kriglerová told The Slovak Spectator, adding that in a time of growing tension in society it is quite possible that a certain part of the population might lean towards extremist groups, since they very often hold the same opinions about some things.

“It looks like that’s exactly what’s happening at the moment in our society,” Gallová Kriglerová noted.

Protesting

Extremist groups in Slovakia seem to be trying to improve society’s negative perception of them, speaking in the name of ordinary citizens and talking about the protection of their own rights, Gallová Kriglerová said.

The police also noted in their report that during 2011 there was an increase in the number of organised protest gatherings (against budgetary measures, in reaction to cases in the media, or even directly motivated by anti-Roma sentiments) that were later abused by supporters of extremist movements.

“The extremist scene in Slovakia underwent a visible change from relative anonymity through civic associations up to the political scene,” the report reads, adding that extremists are using the problems of socially disadvantaged groups of citizens and the frustration of locals.

Citizens’ “only ally”

The far right is now working to convince people that its solutions are the only effective ones, although in reality they are most often technically, financially, and legally impossible ideas, on the level of “pub recipes”, according to Bihariová.

“And since people today are really frustrated and feel that the state doesn’t offer solutions regarding the issues of marginalised Roma communities, the far right seems to be becoming their only ally,” Bihariová explained.

The Slovak political scene continues to walk the line of public opinion, which is tuned to a strong anti-Roma theme, Gallová Kriglerová said, adding that, however, political parties not only listen to public opinion and react to it with their inactivity; they also have the power and ability to form public opinion.

“Their social responsibility lies in the fact that they can influence their voters and therefore it should be in their interest to move public opinion towards higher tolerance and mutual respect of all inhabitants of the country,” she noted, adding that, however, in practice the opposite seems to be happening.

“As long as the state doesn’t manage to take responsibility on a macroeconomic level and doesn’t start to play fair, by directly telling the public that the politics of repression and restriction is a populist road to nowhere, the far right will continue taking the wind out of their sails,” Bihariová said.

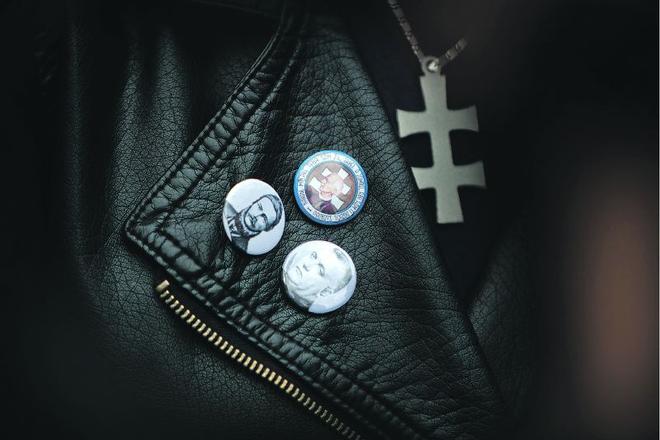

Springtime for Tiso? (source: SME)

Springtime for Tiso? (source: SME)