This is an article from our archive of travel guides Spectacular Slovakia. For up-to-date information and feature stories, take a look at the latest edition of our Spectacular Slovakia guide.

www.spectacularslovakia.sk

www.spectacularslovakia.sk

Slovak wine might be a revelation to first-time visitors, but wine-making here goes back to the 7th century B.C., when Celtic settlers, probably taught viniculture by the Romans, first planted grapes on the hilly land northeast of Bratislava. Slovakia has been on the northern fringes of the winemaking world ever since.

Slovakia's continental climate-hot summers and cold winters-makes it perfect for growing fruity whites and full-bodied reds. Austro-Hungarian nobles prized the white wines produced in the Small Carpathian region near Bratislava, the red wines in what is now southwestern Slovakia, just north of the Hungarian border, and most of all the sweet wines of the Tokaj region, in northeastern Hungary and southeastern Slovakia.

The legacy of Communism

The 20th century all but ruined 2,700 years of winemaking tradition. The Austro-Hungarian Empire fell, two world wars were fought, and communists ruled the lands (and vineyards) for 40 years.

By 1989, Slovak vineyards were churning out loads of cheap commodity wine. The Czechoslovak government even traded away Slovakia's right to sell Tokaj abroad in an export deal with Hungary. Since independence in 1993, a small group of wine-makers, concentrated in the Small Carpathians and in the Tokaj region, have been striving to restore Slovakia's winemaking heritage.

In rural areas, adults were allowed a maximum of 10 acres of land on which to farm, and the rest was collectivized. The bulk of wine-growing land was bundled into huge lots, and cultivated by state workers mainly interested in increasing yield.

The government's crude grading system awarded top prices to Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, and Rhine Riesling (Rizling rýnsky in Slovak). But the yields of these grapes were too low to make them worth planting on a wide scale. Less distinguished and more prodigious grapes such as Müller-Thurgau and Welschriesling (Rizling vlašský) ruled the day.

Meanwhile, centralized vineyards were born. Wine grapes became a commodity, sold to state-owned wineries at set prices.

"In the process, the relationship between grape grower and winemaker disappeared," said Fedor Malík, a Slovak wine authority. State-owned factories produced more than 80 percent of Slovakia's wine. Smallholders produced the rest, for private consumption or barter.

Wine became just another industrial product, like auto parts or machine tools. Quantity soared: by 1989, Slovakia produced a third more wine than it consumed, with the surplus sent to the Soviet Union or to Czech lands. Quality, meanwhile, plunged.

When Communism fell in 1989, the communist winemaking system came down with it.

Since the revolution: a work in progress

Post-communist governments have tried to return collectivized lands to their former owners. But many of the original deed holders have died, according to Igor Šarmír, secretary of the Slovak Grape and Wine Producers Union, so the government split the land into parcels and offered it to their heirs. Often the heirs lived abroad, or there were so many of them that the parcels ended up being too small to be of much use.

"A lot of vineyard land is lying fallow," Šarmír said. "Either no one's sure who it belongs to, or people that have inherited it haven't done anything with it."

As a result, Šarmír said, land planted with wine grapes has fallen from 30,000 hectares in 1990 to 15,000 in 2002.

In recent years, the amount of harvested grapes as well as registered vineyards of around 15,000 hectares in size have stabilised. However, vineyards that produce grapes reported by Statistical office are slowly decreasing. Sadly, Slovakia will probably never reach its former capacity.

The European Union, which regulates commercial winemaking, allows member states to enlarge their currently registered vineyards by 1 percent every year.

The decrease in wine output means Slovakia, which produced a third more wine than it consumed during Communism, now consumes more than it produces. Wine imported from the Czech Republic's Moravia region, low-priced Hungarian imports, and both cheap and expensive wine from France, Italy or Spain make up most of the difference.

Some experts argue that the domestic shortfall actually benefits Slovak wineries, because it allows them to sell most of their wine at home. What's more, the government imposed stiff tariffs in the 1990s on imported wine.

Angela Muir, a writer for the Oxford Companion to Wine, said in 2002 that Slovakia's surplus in demand, along with protective tariffs, has "effectively made it unattractive for Slovak producers to try and compete on the world market. Why should they? They can sell all they make to the home market."

Nor are foreign wine importers, beyond those in the Czech Republic, particularly interested in buying Slovak wine. Producers here "had illusions about how their wines stacked up against competition," Muir said. "There is a huge price gap between what the local market will pay and what anyone else, particularly a British supermarket, will pay."

Our Spectacular Slovakia travel guides are available in our online shop.

So Slovak winemakers have been essentially shielded from the brutally competitive international wine market. Meanwhile, Slovak winemakers can charge higher prices than those in southern Italy, and some parts of Spain, Chile, and Australia, without having to match their quality.

In 2004, after Slovakia became part of the European Union, wine tariffs were reduced or scrapped. Slovaks are thus gaining access to international wines at competitive prices. This forced more Slovak vintners to create concentrated, distinctive wines.

Many of them have succeeded. Slovak winemakers have gained success at international competitions and have surprised wine enthusiasts in other countries with the quality of Slovak wines. They have also embarked on the trend of allowing visitors to taste the wine directly in the places where it is produced.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guides

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to the Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, traveller's needs as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.

(source: Ján Svrček)

(source: Ján Svrček)

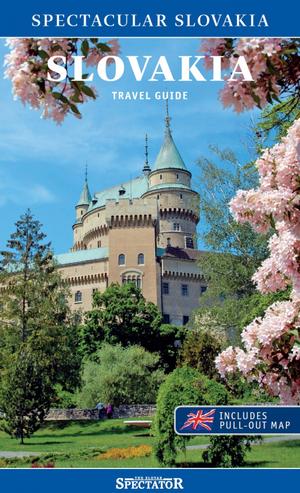

Pezinok Castle (source: Zámocké vinárstvo)

Pezinok Castle (source: Zámocké vinárstvo)