Ukrainian version/Slovak version

On one of his first days in Slovakia, Denys Vasiliev found himself observing trains. As he did so, some tall plants with long leaves and large clusters of flowers that were growing in between the railway tracks caught his eye.

As a child, the Ukrainian loved botany. It did not take him long to identify the plant as milkweed.

“It reminded me of the shores of the Sea of Azov in Ukraine,” he tells The Slovak Spectator.

The plant is known for its medicinal uses; scientists named it Asclepias after the Greek god of medicine, Asclepius.

Vasiliev helps people, too. As a psychologist, the 39-year-old professional helps tackle the problems faced by Ukrainian refugees who have decided to seek refuge in Slovakia since Russia invaded Ukraine in February of last year.

Unlike many other refugees who have been struggling to find a decent, well-paid job in their respective fields, Vasiliev caught a break in Bratislava.

“On the second day after I arrived here, I found that a help centre for Ukrainian refugees needed a psychologist,” he says.

A week later, he was already assisting his countrymen.

An adult who discovers new things

Vasiliev, a refugee himself, arrived in Slovakia from Kyiv last summer to reunite with his wife and two little boys. They had come to Bratislava five months earlier.

“It was like starting life anew, only as an adult,” he says, comparing his experience to that of a child who finds all new things interesting, “Here, I’m also small, but I’m a grown-up man at the same time.”

It was a friend from their student days that recommended Slovakia to them.

In the Slovak capital, his wife Julia gave birth to their daughter. Vasiliev, unfortunately, could not be by her side. As a man of fighting age, he had to stay in Ukraine in case he was called up to join the Ukrainian army.

In wartime Ukraine, only fathers of three or more children are exempted from serving in the army.

Soon after his third child was born, he was allowed to move to Slovakia. In a completely new world, the experienced psychologist quickly found his first job and began to provide other refugees with road maps for their lives in Slovakia, explaining where they can find – and how they can access – different services in Bratislava, all the while learning more about their needs.

At the same time he had to organise his own family life, from finding a good school and after-school clubs for the boys to securing comfortable, affordable housing.

“I suddenly began to interact with Slovak society,” he says.

Vasiliev, who had spent his whole life in Ukraine, also had to learn the language. Though he attended Slovak language courses, he says that he has never attempted to study it. Instead, he has relied on interactions with Slovaks. By his own account, this has worked out quite well.

Staying because of the children

But as his life goes on in Slovakia, he – like many other refugees – keeps asking himself whether he should stay in the country or not. For now, it is a ‘yes’.

“I definitely do not want my children to go to school during constant air raids, or to study in a basement,” he says, “As long as our kids like it here, we’re staying.”

He admits that his boys, aged 9 and 11, struggled in the first Slovak school they went to. There was a language barrier and other children did not accept them. But things have improved since they swapped schools, the father says.

“They like to go to school now,” Vasiliev says, adding that he does not expect his boys to get excellent grades.

The question of education was one that arose quite frequently at the help centre. In addition to helping find schools for Ukrainian children, he met children that had resigned from their studies and refused to continue. Still, these were not the hardest situations, professionally, that he has ever dealt with. In Ukraine, for instance, he worked with people that had to cope with mental health issues during the pandemic, and with children with special needs.

“I encountered this problem in my own family,” he explains, discussing the motivation behind his decision to become a psychologist.

Today, he works as a psychologist with a local Christian charity organisation known as Bratislavská Arcidiecézna Charita. He helps children and their parents.

Slovaks are better at work-life balance

Working with Slovak people, he has noticed a major difference: Slovaks are better at managing their work-life balance than Ukrainians.

“Leaving work late is normal in Ukraine. Here it is weird,” Vasiliev notes.

The Ukrainian says that he has now learnt that Slovak people are not indifferent to work. Instead, he says, they just know when it is time to put work on pause. Conversely, Ukrainians do not go on holiday as often as Slovaks, Vasiliev thinks. He compares Ukrainians to Americans, explaining that they are equally work-oriented.

“Psychologists in Ukraine can hold lectures on how not to burn out at work on their day off,” Vasiliev jokes.

This, in fact, goes against a belief that is widespread among some Slovaks – especially those who are poorer or hold extremist views – that Ukrainian refugees do not work in Slovakia and just live on social benefits. Many actually work in car factories or do jobs that Slovaks refuse to do.

“Ukrainians, if they have the opportunity, they will find their place here,” the psychologist concludes.

This story was published with support from the International Press Institute's Ukraine regional reporting fund.

Working with Slovak people, Denys Vasiliev has noticed a major difference: Slovaks are better at managing their work-life balance than Ukrainians. (source: SME - Marko Erd)

Working with Slovak people, Denys Vasiliev has noticed a major difference: Slovaks are better at managing their work-life balance than Ukrainians. (source: SME - Marko Erd)

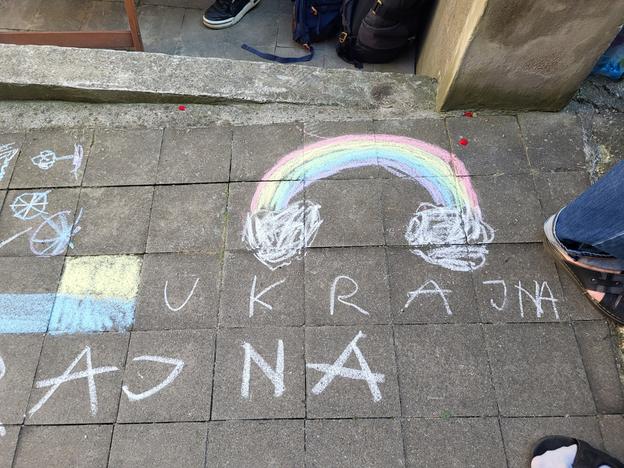

Ukraine-related drawings on a pavement. (source: Bratislavská Arcidiecézna Charita)

Ukraine-related drawings on a pavement. (source: Bratislavská Arcidiecézna Charita)

Denys Vasiliev with children. (source: D. V.)

Denys Vasiliev with children. (source: D. V.)