“Slovakia may be a young country but the Slovaks are an old people.” So begins the tale of the Linden tree, an ancient symbol of endurance, perseverance, and rebirth in the young country that lies in the very heart of Europe.

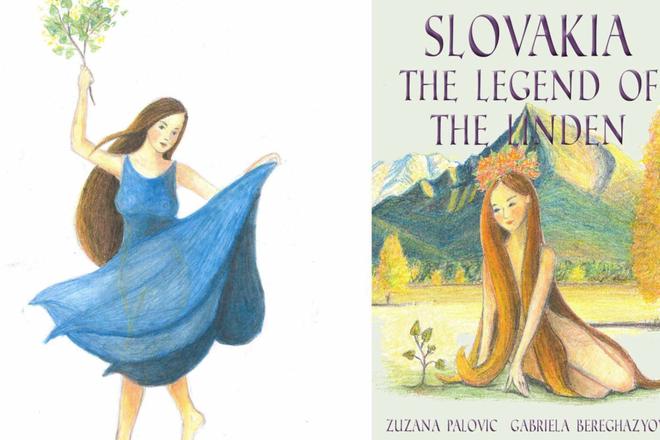

Slovakia: The Legend of the Linden, co-written by Zuzana Palovic and Gabriela Bereghazyova and available in both Slovak and English, explores the dynamic history of Slovakia through the Linden tree, or “Lipa” in Slovak. Though common and often overlooked, the Lipa tree has been used and abused, worshiped and honoured for centuries and is deeply-rooted in the very foundation of Slovakia.

After reading this book, filled with beautiful photos and illustrations, it’s clear that Palovic and Bereghazyova have a flair for the romantic. They examine the history of Slovakia through a creative lens, using rich imagery to paint the historical timeline of Slovakia, moving from Roman occupation past the 1993 Velvet Divorce. However, it should be noted that The Legend of the Linden is not a history book; readers should not search for a detailed and objective view on Slovak history in this story.

Roots of the Linden

The book begins with a description of the Linden tree and the fruit it bears, so to speak. Many still use the Linden blossom to make stress-reducing tea while the tree’s pollen is a vital ingredient in Slovak honey.

“Once the gentle leaf has landed in your hand, its alchemy unlocks the secret door to the empire of the Slavic soul,” the authors write.

They continue that the heart-shaped leaf of the Linden reminds of times when both friends and foes bowed down to the sacred Linden tree during war, passing through the much sought after land that would be settled centuries later by the ancient Slavs.

The identity of Slovak land changed drastically throughout the centuries as one conqueror followed another but according to the authors, the Linden and all it stood for endured. During the Hungarian domination of today's Slovakia, the Linden became a symbol of secret resistance and served as a “weapon of destruction” against the Germans during the Slovak National Uprising.

Readers will also be interested to know that the infamous Vladimir Mečiar abused the Linden symbol during the turbulent 1990’s, handing out Linden seeds at meet and greets before the 1998 elections. His efforts to squash change were thwarted, however, and the Linden became a positive image of Slovakia once again.

A living legend

Today, the Linden tree remains a national symbol of both the Czech Republic and Slovakia and according to the authors has always been an emblem of Slovak identity which ‘‘could not be suppressed forever”.

The Legend of the Linden is a quick and interesting read, regardless of whether readers are familiar with the Linden tree and all it stands for or barely notice the famous tree that sheds its heart-shaped leaves in Slovak parks and forests. Some may argue that the Linden is not as prominent of a symbol as the authors suggest but regardless of what the Linden means to the reader, Palovic and Bereghazyova’s message is clear: despite years of war and turmoil, oppression and opposition, like the Linden, Slovakia still stands.