It was night and the ship raced through the freezing Atlantic. They raced as fast as they could, diverting every bit of steam they could, including for heating and hot water, to power the ship's engines. The crew of the Carpathia knew something unheard of had happened. They rushed to the shipwrecked passengers from the largest, most technically advanced, and most luxurious ship of its time, the Titanic. It was supposed to be unsinkable.

They had already prepared space, blankets, coffee, and tea. Even though they were going full steam ahead, they did not reach the place where the steamer sank until three in the night on April 15, 1912.

Ever since then, the Titanic tragedy has fascinated people. However, one can also look at it from another perspective; from the deck of the Carpathia.

Among those who tried to save the victims was the young woman Júlia Červenková. Her story was unknown until now.

An old, tattered medal

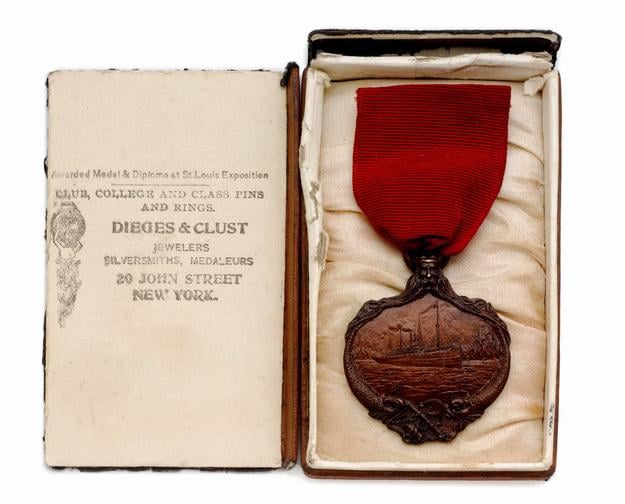

In 2006, when the London auction house Morton & Eden auctioned a collection of old medals, it contained one from the estate of a certain Catherine Livermore from Liverpool. The bronze medal shows an ocean liner amidst icebergs. It is the Carpathia, racing towards the sinking Titanic.

Catherine Livermore had died two years earlier, and the medal belonged to her mother, Júlia. Along with other crew members, the latter received it for saving hundreds of lives from the ocean. While working on the Carpathia during the fateful night, she was still single. Her name was Červenková, and she came from what is now Slovakia.

Her story was discovered by Pavol Horňák, an amateur researcher from Košice who studies the history of eastern Slovakia and the wider region.

"Like many people, I have been fascinated by the story of the Titanic since childhood. During my research, I came across Júlia and the captivating story of her family," says Horňák. "The research is, of course, detective work full of dead ends, which can sometimes be quite distressing. But during a broader search based on initial findings, I found information about Júlia's final resting place, and later I discovered a collection of photographs, medals and memorabilia that undoubtedly belonged to the family."

According to him, communication with the auction company was smooth.

"The artefacts were probably brought to auction from the estate of Julia's daughter Catherine. I wasn't able to learn where these items ended up, but at least the auction house provided me with copies of the documents and medals," he says.

Catherine probably valued the medal very much. The piece that ended up at the auction was worn, she kept it on a bunch of keys, probably as a memento of her mother. While other medals from the auction were much better preserved, the ship motif on this one was almost unrecognisable.

Horňák managed to find out that Júlia worked on the Carpathia as a stewardess. He managed to obtain two rare photographs from the auction house. One shows Júlia with the other Carpathia stewardesses after being awarded with commemorative medals, the women have them pinned to their chests. Júlia is the youngest among them. In the second photo, she is standing on the deck of the Carpathia with Vernon Livermore, her future husband.

Love on the lower deck

They met aboard the Carpathia. Vernon was a steward. While Júlia came from the faraway Kingdom of Hungary, Vernon Livermore, according to Pavel Horňák's findings, came from Cleckheaton in Yorkshire, England. He also helped rescue the Titanic survivors and received a commemorative medal.

In the photo, they are standing by the ship's mast, she in her uniform, he in a suit. She is beautiful, he has a moustache and a smile on his face. The photo was probably taken on the Carpathia shortly before the Titanic tragedy.

At the time, Júlia was 26, Vernon was 6 years older. Little did they know that their lives would be linked until death.

"Julia worked on several ships belonging to the Cunard Line," the researcher explains.