In the heart of Bratislava’s Nové Mesto district, in the post-industrial sprawl known as Dynamitka (a nickname derived from its past as a dynamite factory), one man has been quietly building his concrete palace. Once home to a factory, what’s happening here today might be just as explosive.

Inside this hidden bunker, some of Slovakia’s top musicians are creating everything from hip hop to jazz to industrial. But what exactly is this place — and how did Juraj Somolányi transform an object of war into a house of culture?

Enter the Bunker

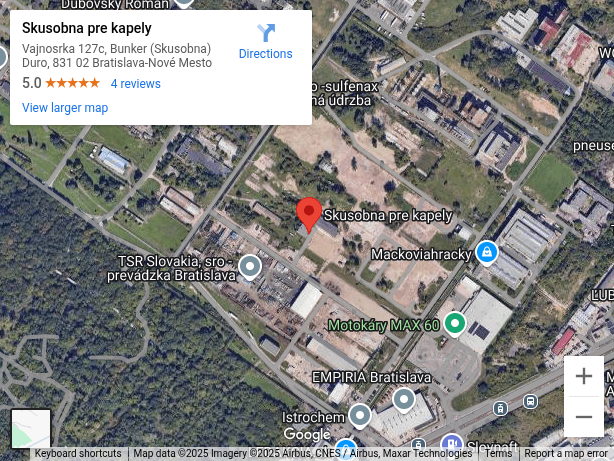

The bunker — now known as Skúšobňa Bunker Music House — lay disused and overlooked from the end of the Second World War until the early 2010s. Then came Juraj Somolányi.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Somolányi was a member of the EBM band The Dark, which received airtime on MTV — even being broadcast in the United States. EBM, or Electronic Body Music, is a fusion of industrial and dance music — fitting, given the location of Somolányi’s bunker: a creative oasis in an otherwise bleak landscape of industrial decay. Somolányi didn’t stay with the band for long. “I was in the band to meet girls,” he says. “Once I took up photography, I realised that was the easier way to do it.”

Since then, Somolányi has worked full time as a prolific artistic nude and music photographer. “I have pictures of hundreds of naked women in my archives,” he notes. Yet he never lost his love of playing music, and in 2011, this passion led him to rent a disused loft in the old Cvernovka complex and convert it into a rehearsal space.

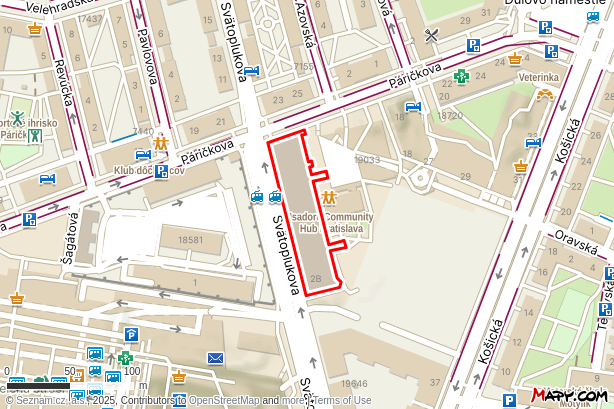

The Cvernovka site, located next to Nivy Tower (a modern office and retail high-rise in Bratislava’s business district), is also part of Bratislava’s industrial heritage. Originally a spinning mill from the late 19th century, it was nationalised in the late 1940s. After the fall of communism, the building became home to a variety of artists’ studios, evolving into one of the city’s key cultural hubs.

Somolányi spent half a year clearing “birdshit and mummified pigeons” from the loft he had rented, hauling thousands of euros’ worth of musical equipment, lights and furniture up a narrow staircase. But just as he finished cleaning and declared victory, he received notice to vacate — his section of the building was slated for demolition. The main portion of the building was redeveloped.

The artists relocated to the larger, more modern Nová Cvernovka complex, housed in a former vocational school that now serves as a vibrant cultural space, replacing the original Cvernovka site. Nová Cvernovka is located on Račianska Street.

Industrial elbow grease

Down but not out, Somolányi eventually stumbled across what would become his future bunker base. While there weren’t as many mummified pigeons to contend with this time, there were a host of other technical challenges.

Heating was the biggest one. When he first stepped inside in January, the temperature was a brisk 5°C. “I decided the only cost-effective solution was to heat the place using a wood burner,” Somolányi says. Easier said than done: it took him four months to drill a hole through the 2.5-metre-thick reinforced concrete wall to install the necessary chimney.

Over the past 12 years, he’s added quite a lot. There are two fully stocked rehearsal rooms equipped with a variety of drum kits, guitar cabinets, microphones, amplifiers, drum sequencers and more. There’s even a dedicated drum practice studio, an outdoor beat lab for hip-hop heads, and plenty of soundproofing.

For downtime between practice sessions, there’s a spacious common room with an honesty bar and a pool table. On the roof, Somolányi has even installed a jacuzzi. “That one’s just for me, though,” he says wryly.

The space has many devoted regulars. One is Juraj Bartal, of the band Random Shuffle Repeat. Playing together since 2005, the band members have only ever performed with each other. Only recently — through another band they met at the Bunker — were they invited to play live for the first time. “For a band with an average age of 46, we thought it was the right time to start performing in public,” says Bartal. “It happened in January this year, at Pink Whale (a medium-sized live music venue in Bratislava), after 20 years underground.”

The unique charm of the Bunker

For Bartal, the Skúšobňa Bunker Music House continues to evolve “into a very convenient, flawless and interesting rehearsal space.” The latest addition, he says, is an energy self-sufficiency solution: solar panels, a generator, and a power bank. Now, even in a power outage, bands can still use the premises in full. “We tested it recently, and for over two hours, bands were able to practise as normal.”

But the space isn’t just for rehearsals. Zari, from the band Transpolune, recorded most of their album in the Bunker.

“Turns out the room’s natural acoustics were a huge asset. The space itself just worked, and from then on it was a question of what recording gear you could get in — and, obviously, how well you could play,” Zari tells The Spectator, adding that “it had the bonus of feeling like home”.

Bartal also spoke of the “unique mojo the Bunker offers”, which he believes “provides a sense of artistic freedom like nothing else”.

The Bunker has attracted several prominent figures from Slovakia’s music scene over the years, including singer King Ivan, pianist Richard Rikkon, singer Natália Hatalová, Elán drummer Boris Brna, Roman “Galo” Galvánek of OBD, folk singer Zuzana Mojžišová, and controversial composer Oskar Rózsa. Rappers like Kali, along with a host of other familiar faces, have also been known to frequent the space.

If a musician or a band is looking for a place to rehearse and connect with others, the Skúšobňa Bunker Music House may not be a bad proposition. In fact, “it’s like another member of the band,” says Bartal.

Zari adds: “There’s something very fitting about making music — this very humane and hopeful act — inside a structure built for protection and survival.”

Dark past

The bunker is one of five located within the grounds of the vast Istrochem plant — over 150 hectares of industrial decay. Known as Dynamitka, the area once belonged to the Alfred Nobel Dynamite Company — the same Alfred Nobel behind the Nobel Prize. Between 1939 and 1945, it came into the hands of IG Farben, the German chemical giant that, prior to the Second World War, was the largest company in Europe. The plant, along with the Apollo Refinery, was used to fuel the Nazi war machine.

After the war, the company was seized and broken up by the Allies. The communists brought the site under state control in the late 1940s, and in 1951 the factory was renamed the Juraj Dimitrov Chemical Plant.

This was in honour of Bulgarian communist leader Georgi Dimitrov, who became the first head of the Communist International. As head of the Comintern for several years, Dimitrov was held in high regard by socialists, and as a result, many streets, buildings and towns in the former socialist world were named after him — from Slovakia to Cuba to Cambodia. One of the names by which the plant is still known today, aside from Dynamitka, is Dimitrovka.

This is not the only echo of Bratislava’s turbulent 20th century to be found across the 150-hectare site. Scattered throughout are several bunkers, distinct from the First World War-era fortifications built by Austrians and Hungarians facing east, or the interwar Czechoslovak ones facing west. Nor are they Cold War fallout shelters. These bunkers were built by the Nazis as part of the so-called Festung Pressburg, or Fortress Bratislava — a plan to turn the city into the Third Reich’s Stalingrad and hold off the advancing Red Army.

The bunker on Vajnorská Street, now serving as a rehearsal space, was originally designed to accommodate around 150 people. It has two floors, stands approximately four metres tall, and its walls are 2.5 metres thick, made of reinforced concrete.

If you're interested in renting the Bunker Music House rehearsal space, you can contact Juraj on Facebook.

Juraj Somolányi stands outside the Bunker Music House (source: Juraj Somolányi)

Juraj Somolányi stands outside the Bunker Music House (source: Juraj Somolányi)