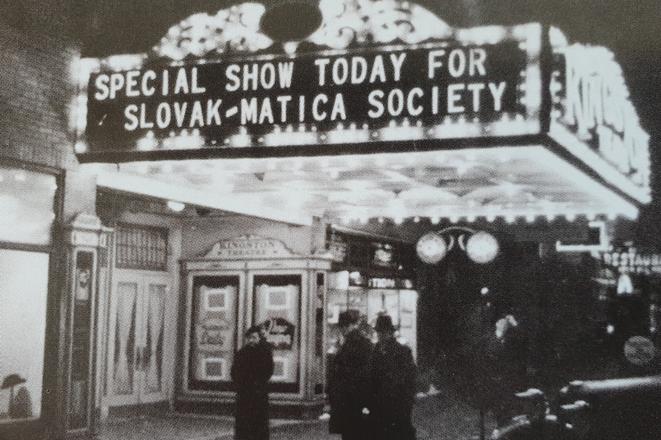

“Welcome Slovak Matica,” reads the luminous sign covering several floors on the building’s facade. It is May 31st, 1936 and the building is Milwaukee town hall. Slovak community living in the city expects the Slovak delegation to come for visit.

Many Slovaks left their homeland at the end of the 19th century or at the beginning of the 20th. Some of them often used their last money to buy a ticket to ocean liner to start afresh in the US. There are no exact statistics from Hungarian offices since Slovakia was part of Hungarian Empire at that time and choosing Slovak nationality in the questionnaire was not possible.

However, data from American ports show that they accepted about 380,000 people at the end of 19th century. Later statistics showed that one quarter could be Slovaks, around 100,000 people. American statistic offices started to also monitor nationality, so we can tell today that until the end of WWI almost a half million people left Slovakia.

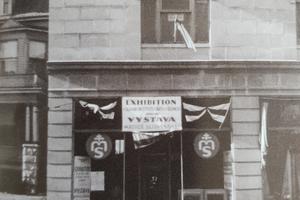

There were huge communities in American cities at the beginning of the 20th century. Slovak expats were active in preserving their national traditions and they created various Slovak societies and organizations. Even documents that heralded the establishment of Czechoslovakia, known as the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Agreement, were signed in the presence of the local societies.

Searching for expats

Matica Slovenská, in that time a respectable state institution that played a significant role in the national and cultural lives of Slovakia, was interested in the lives of the biggest group of Slovak expats on the other side of the ocean. They decided to send a delegation, consisting of Konštantín Čulen, Jozef Cincík, Karol Plicka and Jozef Cíger Hronský, to six-month long journey. Their visit encountered an unexpectedly strong response.

“I would never see Slovakia again, but God sends you, so we can at least feel Slovakia among us,” Jozef Cíger Hronský describing in his travelogue, Journey through Slovak America, how one sightless Slovak expat among others welcomed them to the US.

It was the most powerful welcome speech he had ever heard, Cíger Hronský admits in his book.

Who was Jozef Cíger Hronský?

Jozef Cíger Hronský was a Slovak writer, teacher, journalist, later secretary and director of the Matica Slovenská national cultural institution, which made him a prominent figure of the infamous wartime Nazi-satellite Slovak state.

After the war, he emigrated to Austria and Italy for fear of prosecution. He settled down in Argentina in the end. He remained active in his attempts to work with Slovak expats abroad.

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989 his remains were repatriated to Czechoslovakia and later reburied at the National Cemetery in Martin in 1993.

Slovaks were not always welcomed in the US, Jozef Cíger Hronský writes in his travelogue. America accepted them with mistrust, as they did not know who they were and what state they belonged to.

“Slovaks later proved to America that they are not of unknown origin but members of a small nation without the fortune of being recognised by the world,” Hronský continues in the book.

The delegation visited six main areas where the majority of Slovaks settled – New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Chicago, Scranton and Detroit. They wanted to map the lives of American Slovaks and together they visited 98 towns and cities of the US and Canada where Slovaks lived during the six-month-long journey. They prepared 609 lectures for 170,000 visitors.

“I entered many Slovak buildings in the US and I don’t know why I always felt like entering my parents’ house,” wrote Jozef Cíger Hronský in his travelogue Journey Through Slovak America.

Slovak areas

The first footprints of Slovaks from Trenčín were from the surroundings of Philadelphia; however, they quickly moved further into Pennsylvania. The land of mining was the most famous US state in Slovakia, Hronský writes.

The youngest Slovak area was the one around Detroit in that time. The westernmost area was around Chicago. After a researching the places they wanted to visit, the delegation prepared objects they wanted to exhibit for American Slovaks. Jozef Škultéty, the head of Matica, returned to one specific object several times.

“This will be the most beloved object of many American Slovaks,” he said. Hronský admitted how many times his words became true. Slovak visitors were often standing in front of a Slovak map, shouting at children and showing them: “Look. Here is the village where your mom and I grew up,” they would say as the whole family gathered around the map of Slovakia and tried to read the names of villages, rivers and hills.

Hronský recalled one Slovak ball they attended in New York organized by Slovak National Sokol.

“Words arose behind the tables, it was possible to recognize them according to accent – those were born in Šariš, these in Bratislava, Orava, Nitra, Turiec and Zvolen,” he writes, adding that he did not feel as a guest anymore, but like being home.

He also mentioned the shop windows with signs in Slovak like “fresh eggs”, “Slovak ham”, “Lunch for 40 cents” in certain areas in New York.

“There are several streets where if you shout in Slovak, an echo is certain,” wrote Hronský.

American Slovaks did not forget about the significant figures of our past, as Hronský mentioned. Milan Rastislav Štefánik, for example, has a bronze statue in a park in Cleveland. Once a year in May, the Slovak society gathered around the statue and Hronský described the many Slovak folk costumes he saw and Slovak songs he heard when he attended the gathering to remember Slovak history.

“A legendary hero lives in hearts and minds also here,” he wrote in his travelogue and described that there was also a place for the American Bradlo, parallel of the Slovak monument dedicated to Štefánik.

There were two more Slovak statues in the Cleveland park besides Štefánik- Ján Hollý and Ján Kollár. The Slovak delegation planted a lime tree here, the symbol of Slavs.

“I believe that American Slovaks will continue to water it. If not in Cleveland park than in the national feeling in all Slovak America,” Hronský wrote.

(source: Matica slovenská)

(source: Matica slovenská)