The wooden village, located beneath Brestová, commemorates 50 years since its establishment. Within the village, the stories of people who recall living in the open-air museum with nostalgia and tears in their eyes remain.

“For me, this museum is not just about beauty – which became routine over time – but also the respect and admiration for the people who created it,” Karol Matkuliak who ran the open-air museum for 25 years, reminisces. “There are everyday worries about the operation, unsolved issues of fulfilling the basic functions, as well as existential problems connected with living in detached seclusion but despite all this, I cannot imagine my life without the years spent in the open-air museum.”

Another former manager, Mária Daňová, adds: “Surrounded by the beauty of wood and the nearby nature, you can feel the home where you come from, the roots of your ancestors, their skills, wit, craftmanship, and especially the warmth of home and the love. It is more than a museum; it is our living past.”

In the hearts of those who were – or still are – connected to the Museum of Orava Village in one way or another, this unique place hidden among the mountains has left deep traces.

How the big plan was born

The date was September 24, 1967. On the Brestová clearing, a green, gently sloping meadow, a group of enthusiasts built a stone foundation. This rock became the symbol and start of the Museum of Orava Village, now known nationwide. The initiator of the idea was the then-director of the Regional Monument Centre, Stanislav Dúbravec.

“He came from a village that got flooded by (the artificial dam, ed. note) Liptovská Mara,” says Juraj Langer, author of the ethnographic and town-planning study of the Orava wooden museum. “Everything that was once contained in it disappeared. This is probably the reason why he mused for so long on how to protect precious monuments from destruction. The best way was to move them.”

Matkuliak continued the work started by Juraj Langer. Langer, despite being Czech, admired the Orava architecture when he started to work for the Orava Museum and began studying it more minutely. He studied the wooden houses, their structure, furnishings, and the people who lived in them. The result was a unique study which contained all the information necessary for founding the museum. During the first presentation, then-officials asked him what to do first, how to continue, and whether there were people willing to implement it. “I only said, first and foremost, that we needed tanks for conserving the wood and two big assembly halls. This is how it all began.”

A hard farewell

Ondrej Šiška of Zuberec became the construction manager in 1970. His priority was to coordinate everything so that important deadlines could be met. After getting to know the study, they started to move the wooden houses.

“First, we disassembled them, loaded them into vehicles, and drove the parts to the museum. We then stored them in the hall where they were conserved and gradually put into their current places, one by one,” the builder recalls. “Some of the houses were empty when we came to take them. But in some, people still lived. It was hard for them to part with their property. Some even cried. Often, we had to leave and come back in two or three days, so that they could move peacefully. There were also times when people did not agree with the moving. In these cases, replicas of the constructions were made.”

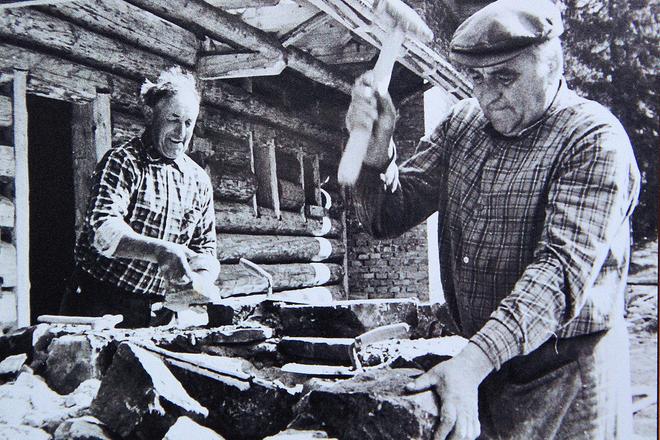

Each beam had to be carefully marked so that carpenters would know where to put it. Ondrej Šiška says that building the wooden bungalows was a lot like building Legos. Each part had to fit perfectly into the others. If some elements were damaged, replacements had to be made. The first building in the open-air museum was an inn from the village of Zákamenné, positioned in a clearing. The original one burnt down in 1990. In its place, a replica currently stands.

The work was not in vain

Carpenters, masons, plumbers, water experts, electricians and other craftsmen worked on the construction of the museum. The technological processes had to be the same as they were in the past-they could not be replaced by new, modern ones. “The plaster casts were made of clay,” Ondrej Šiška explains. “We used sand and swath for them, like in the old times. We did not use bull blood, but most of the materials used were traditional.”

Building the open-air museum. (source: From the exhibition)

Building the open-air museum. (source: From the exhibition)