From mid-May till November 26, 2017 visitors to the prestigious event will be able to watch the installation and enjoy the eponymous catalogue which presents the latest creations and an overview of the artworks of Želibská –the objects, installations, and environments she has made since the mid-1960s, the TASR newswire wrote.

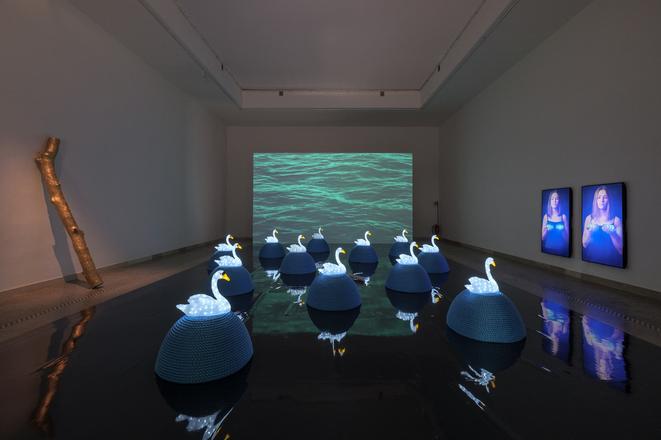

The installation is dominated by a monumental screening of the sea filmed from Venice, while lighted swans dwell on islands representing the eternal yearning for permanence amid a world driven by constant changes, Ladislava Gňačková of the Slovak National Gallery – who organised the competition to select the artist for the pavilion – informed. The wood from the Danube has become a sculpture, while the video-installation points sarcastically to the omnipresent ready-made objects that surround us and create ever more and more the core of our world.

Why Želibská was chosen for Venice Biennale

The jury (composed of Slovaks and one Czech) chose Želibská in October 2016 from among 26 nominations. Two of them made it to the next round and the project of Denisa Lehocká was chosen as the runner up. “Jana Želibská is an important representative of the generation of action- and conceptual artists and of the alternative art scene in Slovakia,” the jury reasoned in its decision. “She was one of the founders of the genres of environment and object in the 1960s, of the action and concept of the 1970s, the post-modern object and installation at the end of the 1980s, and video-art in the 1990s. The continually re-constructed creative programme of Jana Želibská has not lost its power of expression and topicality and with its character of original comments and observations of contemporary times, it embodies the guarantee of relevant representation at the 57th international Biennial of Visual Art in Venice 2017,” the jury wrote, according to SNG.

“On the bank of the Venice lagoon, a place now exists where everyone can come to deeply feel the ode to the famous Venice of the past and the long history of this city,” Slovak artist Alex Mlynárčik wrote for the Sme daily. “Its spirit extends through centuries, times of deep plunges and unbelievable lift-offs. In a silent melody, Jana Želibská managed to pay tribute to this space,” he said of her multi-media installation. Mlynárčik said that Slovakia has filled the Czechoslovak pavilion at the Biennial for four years. (Slovakia and the Czech Republic alternate in representing their nations every second year, with the national galleries of each country selecting the works.)

Artist colleague Mlynáčrik argues

“It seems that the Slovak National Gallery found in Jana Želibská an important representative of the generation of action, conceptual artists and alternative art scene who fulfils the demands of this important event,” Mlynárčik wrote.

Her work approaches a certain sacredness, he added. This is one of the reasons why in the usual clamour of the biennale, in its hectic shouting and dramatic fights for the place in the sun, the pavilion with her work has become a place of meditation, a silent island of thought and consideration reminiscent of Ryoan-ji – the Zen garden in Japanese city of Kyoto. “The mist of the surrounding lagoon reminds us of where we come – and maybe asks where we are heading,” Mlynárčik said for Sme.

Želibská, born in the Czech city of Olomouc in 1941, has created situations not just as an aesthetic experience but also to provoke individual reactions to various issues. In the 1970s and 1980s, she was not allowed to exhibit in the then-communist Czechoslovakia – for political reasons – and she turned to the landscape and land-art. In the secluded space of her Bratislava house and studio, she continually composes objects and installations from the things she finds, their parts and fragments, industrial materials, products of nature and minerals. Since the 1980s, the artist has been using opposites and paradoxes in her installations and video-works. Her more recent works are contemplations on the unstoppable essence of time, on the ephemerality of all things – but with the distance and irony typical of her work, TASR wrote.

Jana Želibská: Swan Song Now / Labutia pieseň teraz; multi-media installation. 2017. (source: Peter Gáll)

Jana Želibská: Swan Song Now / Labutia pieseň teraz; multi-media installation. 2017. (source: Peter Gáll)