In 1914, the First World War began, but for Bratislava the year was important for another reason: the south-German painter Karl Hugo Frech moved in and stayed here until his death in 1945.

Old Bratislava enchanted the artist. “You have to come as a complete stranger into this old town to see how really beautiful it is,” he said. Numerous graphic artworks, paintings, sketches, and drawings in which he recorded in topographic detail the look of Bratislava attest to his fascination. The sites Frech was able to admire a century ago do not exist anymore, as only a portion of the original historical town remains. Thus, the painter’s work is of great documentary value.

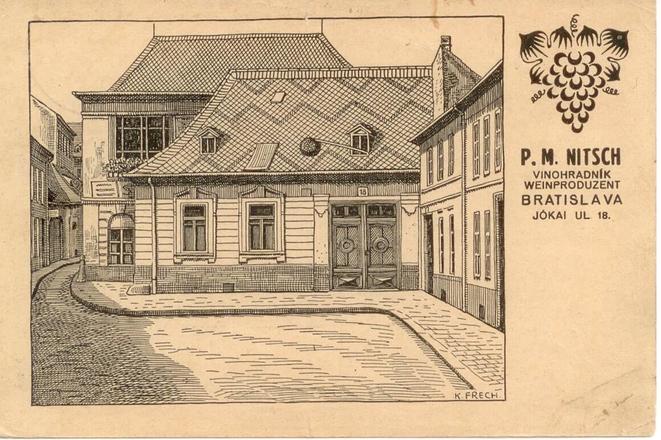

The street with houses in this 1920s postcard is also a matter of the past.

Frech probably created this painting at the order of a family of viticulturists, the Nitsches. They then used it for promotion material, complete with logo, name and data on their company.

House No 18, as seen in the middle of this card, was a typical viticulturists’ building. On closer inspection, one can see a “viecha” sticking out from the roof window. A viecha was a wreath made usually of oak or wine leaves, some were also from pine branches, and it used to announce to everyone that wine is now being drawn at this winemaker family. Katarína Nitschová, from house No 18, first tried to modernise this sign and instead of twigs, lured visitors with lighted electric bulbs.

In the nearby wine-growing municipality of Rača, nobody tried to electrify viechas. Local winemakers used to hang a ball that was made just from conifer branches, but it had an electrifying effect on passersby nevertheless. It was trickily called “the broken arm” and visitors felt obliged to come visit the poor viecha owner who allegedly had a broken arm. As all winemakers in Rača constantly had “broken arms”, their cellars were always full of people.

This article was first published by The Slovak Spectator on 25 May, 2015. It has been edited to be relevent today.

(source: Courtesy of B. Chovan)

(source: Courtesy of B. Chovan)