The author, Renáta Bláhová, is the former chair of the Health Care Surveillance Authority.

The absence of regulation, accompanied by the omnipresent conflict of interest, distorts the financial relations between health insurers and hospitals in Slovakia. This leads, among other things, to hospitals being financed mainly by the state-owned insurer Všeobecná zdravotná poisťovňa (VšZP).

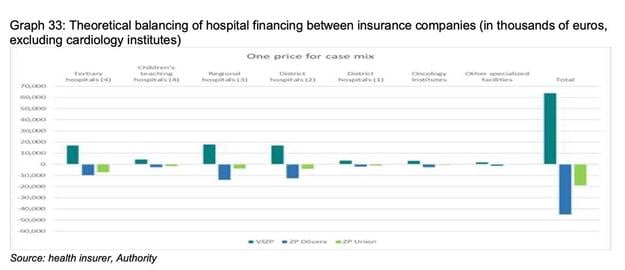

The insurance company Dôvera, owned by Penta Investments Limited, pays the least per unit of output — we first reported on this during my time at the Health Care Surveillance Authority (ÚDZS — Úrad pre dohľad nad zdravotnou starostlivosťou) in 2022. At that time, the payment deficit for this insurance company amounted to more than €40 million for hospitals alone (see official graph below).

In 2023, matters did not improve with Dôvera, despite the fact that it lamented in the media throughout the year that it was generating losses because "there is not enough money in the healthcare sector" — a claim that is not true. The total amount of resources flowing into the healthcare sector is comparable to countries of similar economic strength to Slovakia; however, this is not adequately reflected in the quality of health care or citizen satisfaction.

At the end of 2023, private health insurers reported a profit of around €20 million; Dôvera’s figures for 2024 are similar. The calculus is simple — to benefit from public resources either through "our hospitals" or through "our insurance company", while the weak state remains silent.

In the pursuit of profit, predatory capital often invests in local elites; financially, this continues to pay off even though, since 1 January 2023, health insurance company profits have been capped. For some elites, all that is required in return is a polished image in the related News and Media Holding (NMH) group, also owned by Penta Investments Limited, and invitations to related panels at conferences.

But sometimes the elites go off the rails, as in the case of Marián Petko, who has been President of the Slovak Association of Hospitals for more than 20 years.

Non-transparent negotiations under the Association’s cover

In 2022, during my time at the ÚDZS, we began focusing on these practices. We established an analytical unit and examined closely the mechanisms of price negotiation in inpatient health care.

It was mainly the Association that surprisingly resisted transparent remuneration based on quality and performance during negotiations with both the ÚDZS and the Health Ministry, while representatives of state hospitals mostly sat quietly in the corner.

As a newcomer to the negotiations, I was unbiased. I openly asked why the insurance companies and the Health Ministry were negotiating only with the Association, headed by Marián Petko, and not directly with the individual shareholder representatives, such as the directors of Penta and Agel hospitals, to ensure greater transparency. This would have considered the actual performance of hospitals controlled by Penta and minimised the risk of bundled ownership abuse (where a major health insurer and hospitals share the same owner). I did not receive a satisfactory answer.

More or less, everyone referred to the fact that this was a 'historical approach to negotiating contracts' and that, in Slovakia, budget discussions are typically framed around the percentage increase in payments compared with the previous year, rather than considering whether the payments as a whole are fair and reflect the actual performance of hospitals.

Anecdotally, the sector speaks of better- and worse-paid unions and hospitals, depending on who stands behind them. I wrote about this in more detail last summer. One consequence, among others, is the continued indebtedness of state hospitals.

Despite the ÚDZS’s findings of unfair funding for 2022, the Association claimed early the following year that "representatives of health insurers, in negotiations with Association members, reaffirmed a claim of €238 million. However, the Association is concerned that if these promises are not promptly turned into reality, there will be a real threat to social reconciliation."

At that time, the package was intended for district hospitals alone, with a total value of around €400 million.

It was not only the media narratives that were aggressive; in fact, there was a dictate from the Association. No one objected to this except the ÚDZS, although its competences were insufficient. It appeared that everyone — the insurers and the ministry alike — was complicit in a long-standing system in which two powerful financial groups dictated terms while the rest of the sector stood by silently.

Among non-state institutions, only the Doctors' Trade Union Association (Lekárske odborové združenie) openly supported the ÚDZS in its push for transparency; thanks to their efforts, a commitment to launch DRGs as a reimbursement mechanism was, for the first time, included in a memorandum with the government in October 2022.

When the President of the Association, Marián Petko, was convicted in late 2022 in the first instance by the Specialised Criminal Court for corruption at the Bardejov hospital, where he serves as director, it was again only the ÚDZS that publicly appealed to the Association and its members to take action.

Instead of self-reflection, the Association's Petko-Petko Doctor duo sued the ÚDZS and, surprisingly, obtained a court ruling in 2023, after which the Communications Department was required to withdraw the appeal from the ÚDZS’s website.

It seemed inconceivable to me that such a person could be entrusted with negotiating the redistribution of hundreds of millions of euros on behalf of the private sector. Recently, the Supreme Court published its final verdict, confirming the conviction of the Association’s President for accepting bribes.

Marián Petko has served as President of the Association for more than 20 years. According to information released last month, he only suspended his function, despite enormous pressure, and the Association expressed its continued support for him despite his conviction.

During his absence, the Association will be represented by its long-time first vice-president, Igor Pramuk, who works for Penta and, at the same time, serves as the state's nominee at the Bardejov hospital — a conflict of interest he sees no problem with.

Bojnice hospital worth following

The first to react on social networks was the director of Bojnice hospital: "As of yesterday, Wednesday 12 March 2025, our Bojnice hospital is no longer a member of the Slovak Association of Hospitals. We found that if we had set payments for inpatient care last year at the level of the Association’s private hospital members, we would have had about €5 million more income in 2024. And that's just the difference with the largest insurance company and only for inpatient care."

He added that from now on, they will negotiate directly with the insurance companies.

This is the right step to take, and it requires courage in our health care system. Encouragingly, the two biggest players — Penta and Agel — have so far remained silent, despite the long-standing rumours of a possible cartel between them, known informally as Pentagel.

Although the cooperation between these two oligopoly-dominating players occasionally escalates into competitive skirmishes, they ultimately divide up their territories rationally, with most puppet directors of state hospitals resignedly waiting to see what deal the private hospitals, represented by the Association and Marián Petko, manage to negotiate.

Should Bojnice hospital be followed by others, it could mark a major turning point towards a fairer distribution of resources.

In recent years, the dominant player in the redistribution of money to district hospitals has clearly been Agel. However, the undisputed winner in the race for profits over the past 20 years has been the Penta group — largely thanks to its globally unique cross-ownership structure. Through the same shareholder, Penta controls the insurance company Dôvera, dominates a network of polyclinics and hospitals under Penta Hospitals, and operates the most profitable part of the Dr. Max pharmacy chain, whose business practices are themselves controversial from a competition perspective.

What the Antimonopoly Office is investigating

Competition between businesses is supposed to reduce costs and improve the quality of products and services, and in the healthcare sector, it should enhance patient care. However, the reality appears to be quite the opposite. Competition in inpatient healthcare is largely illusory; indeed, the Association has scarcely even attempted to pretend otherwise.

According to a press release, the Antimonopoly Office initiated administrative proceedings on 7 February 2025 regarding a possible cartel agreement among businesses providing inpatient health care.

This move follows an investigation during which the Antimonopoly Office carried out unannounced inspections last year, obtaining documents and information indicating that four businesses operating in the sector may have colluded on setting prices, coordinated their negotiations with health insurers, and exchanged sensitive commercial information.

Last October, the daily Sme reported that hospital managers had their mobile phones and computers seized, and that the Antimonopoly Office had raided hospitals linked to the Association, suspecting the hospital networks of forming a cartel — allegations that Penta and Agel deny. As usual, they regard any related questions as defamatory to their reputations.

In this context, it leaves a bitter taste that they saw no issue with retaining the convicted Marián Petko as President of the Association — or that they simply chose not to address the problem.

While the initiation of administrative proceedings does not necessarily mean that the businesses have violated competition rules, nor does it prejudge the conclusions the Antimonopoly Office may ultimately reach, it is highly likely that the Association’s role in facilitating unfair agreements among several players will be a key focus of the investigation.

As the Antimonopoly Office does not provide further information at this stage of the proceedings, we must remain patient.

If such an agreement is proven, the companies involved could face fines of up to 10 percent of their turnover for the preceding closed accounting period. More importantly, it would create renewed pressure for fundamental reform of economic relations within the Slovak healthcare sector.

A corridor in a Slovak hospital. (source: SME - Marko Erd)

A corridor in a Slovak hospital. (source: SME - Marko Erd)

(source: UDZS (Health Care Surveillance Authority in Slovakia))

(source: UDZS (Health Care Surveillance Authority in Slovakia))