Jeanne M. Zulick is an attorney and the author of several books for middle grade readers including Each of Us a Universe, A Galaxy of Sea Stars, and Ruby in the Sky. In 1991, she was one of the first Americans to teach at the Gymnázium Párovská in Nitra, Slovakia, through Education for Democracy, a program that introduced conversational English to Slovak students. She lives in Connecticut with her family.

Jeanne M. Zulick’s story is part of a Global Slovakia Project- Slovak Settlers, authored by Zuzana Palovic and Gabriela Bereghazyova. The book is available for purchase via info.globalslovakia@gmail.com.

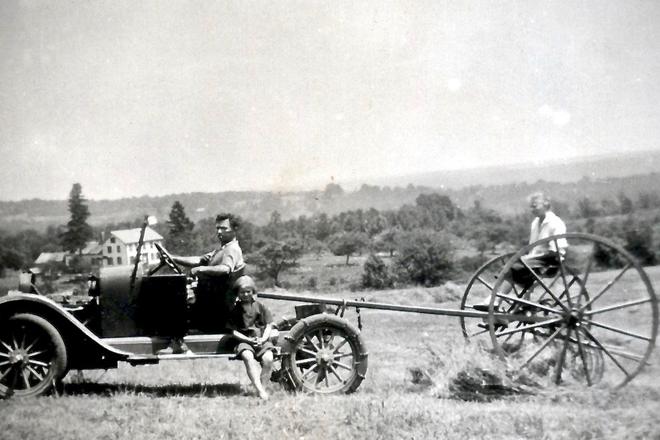

My grandfather Andrej Zozulič was born in 1893 in Parihuzovce, Austria-Hungary. His family was religious, celebrating as Slovak Greek (Byzantium) Catholics. The ship’s manifest identifies him as Ruthenian. Life in what is now eastern Slovakia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was harsh. People drew life from the earth. Labor was done manually. Hay was cut by hand; fields were plowed with oxen.

Healthcare was non-existent; there were no doctors or medicine. Out of the 11 children in Andrej’s family, six perished from pneumonia and other illnesses.

Andrej never had an opportunity for education. Neither he nor his ten brothers and sisters had access to schools or teachers. Andrej’s mother could not read or count money. Likewise, his father, Michal Zozulič, was illiterate, but he proudly served as the popular and well-liked mayor of Parihuzovce.

Even as a young child Andrej worked on the family farm—tending to sheep, oxen, and horses. His long day would be divided into working the horses and oxen during the day, and then feeding and pasturing the animals by evening. It was a lot of work for a ten-year-old child.

In the winter, the family would make shingles and sell them to earn money for fuel. One time Andrej secretly took a few of the shingles his father had made and brought them to the market where he sold them for ten cents each. He ultimately confessed that he wanted to buy a prayer book. His father scolded him, but bought him the prayer book, telling him not to do it again. He would find the money for what was needed.

Christmas was a time of celebration. The festivities and prayer continued for three days. The family would go to the brook, chop the ice, and wash their faces as was the custom in the Byzantium Catholic culture. Then they would take a lit candle and some bread to feed the cattle in the barn before eating themselves. It wasn’t just a ritual or a tradition, it was a mark of respect to the animals who were a part of the family.

The community that Andrej belonged to fended off hardships and poverty with togetherness. If a building needed to be constructed, Andrej would head into the woods with the oxen, and men would help stack wood, bringing timbers to build simple homes with straw roofs. When grain was brought in, the neighbors helped each other process and divide the produce.

When Andrej turned 18 years old, he faced conscription into the Austro-Hungarian army and, like many others, chose to flee his homeland. Although it was illegal to leave the Empire without having completed the mandatory military service, many Slovaks felt no debt to the oppressive Magyar government who aimed to erase their culture and language. Of course, leaving was not without its dangers. If Andrej was caught by the Hungarian guards who patrolled the country border, he would be jailed.

Andrej’s older brother Ján had left for America two years earlier, having used the services of a people smuggler. Likewise, Andrej paid a man who knew where the guards were located and how to avoid them. For two days, this man led Andrej and others through the woods into Russia which then stretched all the way to the borders of Austria-Hungary.

The final European destination before setting sail to the “new world” was the port city of Trieste. It was an arduous journey from Parihuzovce, Slovakia, to Trieste, Austria, via the detour of Russia, but on December 23, 1911, Andrej arrived to board the SS Argentina. But the ship did not leave as scheduled. Apparently, the captain held its passengers hostage, requiring more money before he set off across the Atlantic. Andrej reported that the steerage was so cold that he woke to find that his clothes had frozen to his bunk. Twenty-six days later, Andrej finally disembarked in the Port of New York. During processing, his name was changed as with many other newcomers, and this is how Andrej Zozulič became Andrew Zulick in America.

From New York, Andrew travelled to Pennsylvania to join his brother, John, to work in the coal mines. For three years Andrew dug and loaded coal for 30 cents per ton. Each morning he would leave the boarding house where he stayed before the sun was up, and not return home until after dark. He went months without seeing sunlight.

After those years, he left Pennsylvania and the coal mines and moved to Weirton, West Virginia, to live with his sister Mária and her husband. There, he worked in the steel mills for 15 cents per hour for 12 hours per day. That was a tough job. He stayed for three years before returning to the coal mines. When the miners went on strike, he switched to the West Virginia mill again. In 1914 when the war began, Andrew registered for service in the U.S. Army but was never called.

About the same time, a girl named Irén Filyová lived with her mother, father, and three siblings in Remetské Hámre, Austria-Hungary. They lived in a one-room house with a dirt floor. There was a stove in one corner and a bed in the other. The children slept on benches or on the floor in winter and in the hay field in the summer. The family had their own piece of land where they grew grains, potatoes, and cabbage, but it was a difficult existence.

Poverty pressed the father of the family to look for other ways of earning a livelihood, so he left home, travelling to Pennsylvania to work in the coal mines. He saved all his money, sending it home, so that his family could join him. When they had enough money to secure passage, 12-year-old Irén along with her mother and siblings traveled to the Port of Bremen in Germany, where they boarded the SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie.

The time aboard the ship was difficult. The family was relegated to steerage. Irén’s mother became very sick, and Irén was left to care for her baby brother. To get food, she would stand in line with a bucket to receive her family’s ration. According to Irén, on the day they were distributing sauerkraut, she took the food downstairs to her family and then went back in line to get more because it was her favorite.

Wealthier families stayed on the upper decks. Wealthy children would throw pennies down to the poor kids to watch them jump to gather up the money. But Irén could not get any of the coins, because she was holding her little brother, Antal. A lady on the higher deck saw her crying. She spoke to Irén in Hungarian; Irén responded, and the woman threw her a bag of fruit. “We didn’t know what to make of the banana,” Irén once reported. From then on, that same lady watched for Irén and threw her a bag of fruit each day for the remainder of the trip.

After 17 days at sea, the family arrived in New York in the summer of 1913. During processing at Ellis Island, Irén Filyová became Irene Fello. The family got on a train to Pennsylvania and received a package of food—sardines, bread, and salami that was to last them for their journey. But there was a delay, and they arrived a day late. Her father, unaware of the delay, was nowhere to be found. Not knowing what to do or where to go, all the while not speaking a word of English, the family had no choice but to spend the night in the train station. A woman walked into the station the next morning and Irene’s mother tried her luck speaking Hungarian.

The lady understood and directed the family to a nearby boarding house owned by her sister. At long last, they found their father. The family was finally together again. That fall, Irene and her siblings started school. They could not speak any English. The town kids would knock them around and make fun of them calling them “green horns.” The next spring, a neighbor told Irene’s mother that a woman in another town ran a Hungarian restaurant and needed help. Without having completed even a year of school, Irene’s mother wrapped up her daughter’s few belongings and sent 13-year-old Irene off to work for this stranger.

Irene labored at the restaurant for two years, earning $1.50 per week before moving to Weirton, West Virginia, to work in a can factory for $12 a week. That is where she met Andrew Zulick. Andrew visited Irene’s aunt’s house to borrow a Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog to order clothes. He used the opportunity to ask Irene out to the movies. She said she had to ask her aunt. He asked her “how will I know you’re going to go?” She replied, “If I’m on the porch dressed up, then you’ll know.”

The next day Irene was on the porch, but Andrew didn’t stop; he continued past the house. Irene didn’t know what to do, so she followed him to the theater. After a couple of months of seeing each other like that, Andrew expressed the desire to get married. Irene replied, “Well go ahead, get married.” He explained that he wanted to marry her, but Irene was only 17. She asked her aunt what to do. She replied, “Close your eyes and marry him.” Although Irene’s mother disagreed, the letter she wrote telling Irene not to get married arrived too late. Andrew and Irene were already husband and wife.

After the wedding, Andrew and Irene lived with Andrew’s sister and her husband. The new family saw no future in the mills or coal mines, so when they discovered a farm for sale in Connecticut, advertised in a Slovak-language newspaper, the two families moved to Ashford, Connecticut. They began as poultry farmers, selling eggs and baby chicks until they had enough money to buy dairy cows. Then, they sold the milk for five cents per quart.

But it wasn’t enough money to support the farm and two families, so Andrew had to take on another job. Each Sunday night, he would walk 12 miles to the neighboring town of Stafford and then take a trolley to Hartford to work in a rubber plant. He always brought his food for the week—bread, eggs, and butter, to save money. On Saturday morning, he would return home to the farm to work. He would start all over again the next evening.

For three years, the two families worked as partners, but the farm could not sustain everyone. Disagreements arose and the partnership broke up in 1922. Andrew and Irene took the risk, paid off the other family, and took on the mortgage. It would take them 20 years to pay it off. At the time, more and more immigrants were coming to Ashford to buy farms which were selling at low prices.

Some of the older residents did not appreciate this influx of newcomers, but Irene and Andrew persisted. They also made it through the Great Depression that hit in 1929. The couple continued to work their farm and raise three children. The eldest daughter Margaret recalled starting school without understanding English, because only Slovak was spoken at home. This was the norm for most immigrant families.

Citizens in town also made it difficult for newly arrived Slovaks and Hungarians to gain American citizenship. Irene had become a U.S. citizen before meeting Andrew but lost her citizenship by marrying him, because he was not yet a citizen. Eventually, Andrew gained U.S. citizenship in 1929, and Irene regained hers in 1932.

Andrew and Irene were religious. As more Catholic immigrants came to town, they wrote to the local bishop asking him to send a priest to serve the growing community. It worked, and a house in the center of town was bought, walls were removed, and a partition was made to turn it into a church. Now they just needed a priest, but the parishioners were too poor to pay any wages. So Father Dunn arrived with his own farm animals. He ultimately became a pillar of the community.

Previously settled residents made it clear that they did not like these “different” people with their “different” religion and subjected the newcomers, many of whom were Catholic, to petty attacks, heckling, and harassment. These encounters intensified, turning increasingly violent. Men, dressed in sheets, began making night-time raids at local farmhouses. The intention was to terrorize their immigrant neighbors. Wooden crosses were set ablaze on the hill of the cemetery near Irene and Andrew’s farm. The message was clear: You ‘foreigners’ are not welcome.

Despite the best efforts of these instigators, the new priest, and the Slovak and Hungarian immigrants, did not frighten easily. After all, they were descendants of a people who survived an endless procession of wars, uprisings, and famines. Instead, they fought this prejudice with renewed strength. This included economic strength. Father Dunn helped the new immigrants form a cooperative store where parishioners exchanged their produce for groceries; the produce, in turn, was sold in city markets. The store grew and prospered, and soon trucks were needed to transport all the goods.

With patience and dedication, the Slovak and Hungarian farmers put together enough money to build a proper church. The farmers gathered stones from their own fields. These stones framed St. Philip the Apostle Church.

Father Dunn continued to help the immigrants find their place in their adopted town and country. He wanted to show them that they were welcome, and that this was their home too. He formed a band, gathered donated instruments, and planned a parade for the new immigrants to march proudly down the main street on the Fourth of July. Again, local citizens tried to prevent this, so Dunn hired a police officer to escort his new band.

Life went on and the children of Andrew and Irene grew up, married, and started families of their own. All three remained in Ashford, Connecticut, to raise their families. Today, several grandchildren continue to call Ashford home.

Angel Wings (Božie milosti)

5 egg yolks + 1 whole egg

1 shot glass of pálenka (whiskey or good brandy)

½ tsp baking powder

A pinch of salt

¼ cup powdered sugar

2 cups flour

Vegetable oil or Crisco for frying

1. In a large bowl, beat the egg yolks, whole egg, and whiskey together until blended.

2. Mix in the baking powder, salt, and powdered sugar.

3. Add the flour and beat until the ingredients come together to form a dough, about five minutes.

4. Working with half of the dough at a time, roll it out as thin as possible (as thick as two pieces of paper), on a lightly floured board.

5. Cut the dough into 2”-wide strips. Cut these strips on the diagonal, at 4” intervals, creating diamond shapes.

6. Cut a slit lengthwise in the middle of each diamond.

7. Pick up one end of the diamond, push it through the slit, and tug it back toward its original position. This forms the diamond into “angel wings.”

8. In a large, deep skillet, heat 2” of oil to 350°F (180°C).

9. Fry the pastries for one minute (or less) per side, or until golden. The pastries fry quickly, so watch them closely.

10. Remove the pastries from the oil with a slotted spoon, and place them on paper towels to drain.

11. Serve the angel wings dusted with powdered sugar.