While the Slovak government is busy preparing public finance consolidation package, the European Commission has published its Annual Report on Taxation 2024 focusing on the latest trends in EU tax systems. The report aims, among other things, to help the EU stand as an attractive market in the global competition for investors. Despite all the challenges Europe has faced in recent years, it has managed to keep e.g. its effective corporate tax burden low. On the contrary, the report remains critical of a too high tax burden on labour.

The Annual Report on Taxation 2024 is based on a survey in EU member states and focuses on reforms, but also on the so-called tax mix, which has a significant impact on the behaviour of players on the European market.

Why high burden on labour is a problem

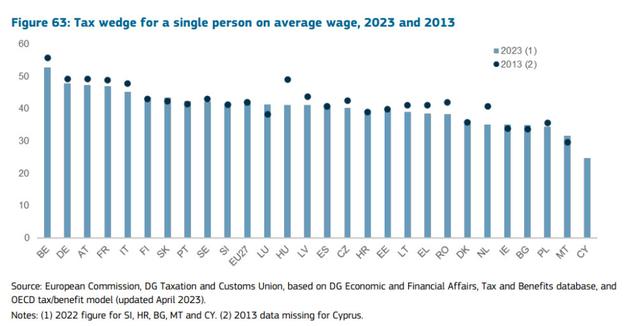

Even though the tax and social security burden on labour has been falling slightly in the EU over the last 10 years (with the exception of Slovakia and a few other countries), it remains very high compared to other economies. In the competition for global investments, this factor plays a key role. According to the annual report, the average difference between total labour costs from the employer's perspective and the net income of an employee is 34.6 percent in the OECD, but as high as 41.6 percent in the EU.

Tax wedge (difference between the total labour costs and net wages) in percent

More on EU tax mix

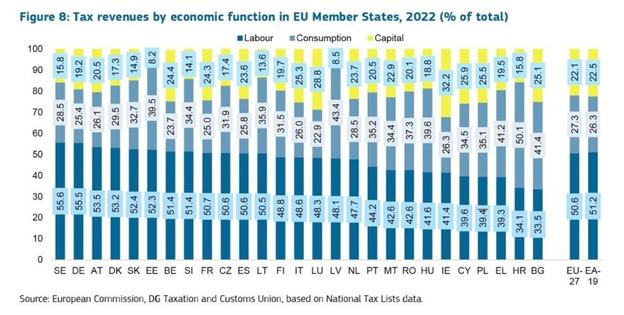

In EU countries, the share of revenues from tax and social security burden on labour is too high, 50.6 percent on average in 2022 (compared to 52.4 percent in Slovakia).

The burden on labour is followed by excise duties, including VAT, with a share of 27.3 percent (32.7 percent in Slovakia).

Next in order are property taxes, including real estate taxes, referred to as capital taxes; their share in the EU-wide tax mix was 22.1 percent and in Slovakia only 14.9 percent.

Tax revenue split by economic function in EU countries (percent)

(Labour taxes are shown in blue, consumption taxes in grey and property taxes in yellow.)

The Financial Transaction Tax – known as FTT – was proposed by the European Commission in 2011. Its aim was to prevent fragmentation of tax policy in this area across member states and to tax mainly low-value-added transactions, including speculative transactions. Common banking transactions of citizens and companies, including deposits and loans, were explicitly excluded from taxation. The proposal was to harmonise the tax base and set minimum rates; for trading in shares and bonds it was 0.1 percent. If such a tax had been introduced uniformly across the EU, it was estimated that it would have already generated more than €50 billion.

However, the proposal for a uniform EU-wide tax has not been adopted, so it has remained fragmented and expectations of its collection are very far from the original estimate, even though the tax rates are higher. In the case of Hungary, which has gone its own way since 2013 and contrary to the original proposal, even common payments are being taxed. This was objected to by the European Commission, as it has implications on the free movement of capital guaranteed by the EU Treaty.

The FTT is a property tax. A detailed report is being prepared by the European Commission for next year, so far it has data for 2017 for five countries in a limited form. A very brief summary is presented in the table below.

Country | Tax base | Tax rate | Income (mil. €) |

Belgium | Securities and stock exchange, insurance transactions, long-term savings, bank profits | Differing rates according to transaction amount | 296 |

Greece | NA | 2 percent | 227 |

France | Securities issued in France for admission to a regulated market with a capitalisation of more than €1 billion | 0.3 percent | 1,100 |

Hungary | Payment services, loans, currency exchange | 0.3 percent, max. 6,000 forints | 700 |

Italy | Stocks and high frequency trades, derivatives | Differing rates according to transaction amount | 432 |

Source: TAXUD, EC |

Trends in Slovakia, the consolidation package and our competitiveness

So far it is clear that the EU as a whole is facing unfavourable economic developments, with the German economy, which has been the biggest driving force of our growth since Slovakia joined the EU, doing particularly badly.

The details of the large consolidation package of around €1.5 billion, which will determine the future direction of Slovak tax policy, are still unknown, but it is planned to increase taxes and, at the same time, to reduce spending. From the partial information released, the main topics of discussion are an increase in social security contributions, i.e. a further increase in the already high burden on labour, a 1 percent increase in corporate income tax and, over the weekend, the prime minister also admitted an increase in the basic VAT rate. The finance minister repeatedly confirmed that the FTT will be introduced based on the Hungarian model, but it is not intended to affect citizens and will probably be targeted at the business sector.

If we do not want to fall even deeper in the competitiveness rankings, instead of increasing, we should reduce the tax and social security burden on labour, and further decrease the VAT gap. If the unprecedented increase in health insurance contributions since January 1, 2024 (a 10 percent increase from the perspective of employers) is accompanied by a radical increase in social insurance contributions, Slovakia's taxation of labour could push Slovakia to EU's tail.

As far as corporate income tax rates are concerned, personally, I am opposed to raising them. Although it is not a decisive factor from the point of view of competitiveness, an increase in the rate will be a bad signal to investors. If the corporate income tax rate is increased from 21 to 22 percent, we will once again, after a long time, not only have a rate higher than the EU average (21.2 percent), but the highest in the V4 region – by comparison, Hungary has 10.8 percent, the Czech Republic and Poland only 19 percent.

Regarding a possible increase in the basic VAT rate, which was admitted by the prime minister over the weekend, it would certainly be a more reasonable step, as consumption is growing and the current basic VAT rate of 20 percent in Slovakia is not only below the EU average (21.5 percent), but also the lowest in the V4 region. In Hungary it is 27 percent, in the Czech Republic 21 percent and in Poland 23 percent.

Given the EU tax mix, the finance minister has the largest space for raising revenue in the area of property taxes. However, rather than introducing a new FTT contrary to the EU concept, it would be more reasonable to dust off the once prepared but not implemented real estate tax reform. If the government decides to follow Hungary's example of FTT, it may be disappointed. Unlike Hungary, we are in the eurozone and it is not a problem for any major business to open an account in a neighbouring country; after all, the EU treaty guarantees free movement of capital. In addition to worsening the business environment, such a tax may trigger a mass transfer of accounts abroad and a drop in bank profitability. Slovak banks would then pay less tax to the state, which could mean that the introduction of this tax would have the opposite effect. Furthermore, it could bring further tensions with the EU if the new FTT contradicts its original concept and the free movement of capital.

However, there is clearly a lot of space for consolidation of public finance on the side of expenditures, for example salaries in the overstretched public administration or health care expenditures, which even the prime minister has already described as "an atomic bomb in terms of financing". In this field there is plenty of space for consolidation, in hundreds of millions of euros, as we do not have regulated prices in the Slovak healthcare sector, even though this €8 billion sector is controlled by an oligopoly with predatory capital and the public health insurance system is full of other European anomalies. Unless systemic changes are made, we will continue to be the only EU country to move closer to the privatised American model, where health care per capita is not only twice as expensive as in EU countries, but also difficult to access for an average citizen.

Renáta Bláhová is partner at BMB Partners TAXAND and member of the Advisory board of the Slovak-German Chamber of Industry and Commerce

Illustrative stock photo (source: Pixabay)

Illustrative stock photo (source: Pixabay)